Getting to the heart of the problems with Boeing, Takata, and Toyota (part 3): Toyota, Takata, and cognitive biases

This four-part series looks at what recent fatal Boeing 737 MAX aircraft crashes have in common with the Toyota and Takata automotive recall scandals, and proposes a solution.

In the first article of this series, I look at medicine’s aspirations to be more like aviation in how it manages the serious problems that are arising at the complex interface between people and technology. However, as I alerted, the recent shocking fatal crashes of new Boeing 737 MAX aircraft show that aviation really isn’t the role model that medicine thought it was. In the second article of the series, I argue that the 737 MAX tragedies highlight shortcomings in Boeing’s knowledge management (KM) program.

In this third article, I reveal that unfortunately it’s not just aviation and medicine that are experiencing life-threatening problems at the complex interface between technology and people. I also show how cognitive biases play a role in this.

There are disturbing parallels between the current situation with Boeing and two significant automotive industry recall scandals. The U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) advises that an automotive industry recall is issued when a manufacturer or government transport safety agency “determines that a vehicle, equipment, car seat, or tire creates an unreasonable safety risk or fails to meet minimum safety standards.” As NHTSA data1 shows, the number of vehicle recalls each year is very considerable, and has grown over time. The recalls cause inconvenience to motorists, and replacing or repairing defective items comes at a significant cost to automotive manufacturers. Major recalls can also result in serious reputational loss.

Two of the most notorious automotive industry recalls are the recent Toyota sudden unintended acceleration recalls and the current Takata airbag recall.

Toyota sudden unintended acceleration recalls

In 2009 and 2010, leading carmaker Toyota recalled2 millions of vehicles in relation to sudden unintended acceleration (SUA) that had caused numerous accidents. The first recall, issued on 2 November 2009, was to correct the possible incursion of the front driver’s side floor mat into the foot pedal well, which could cause pedal entrapment. The second recall, issued on 21 January 2010, was initiated after some crashes were shown to not have been caused by floor mat incursion.

A February 2010 report3 from Safety Research & Strategies, Inc. reveals the background to the recalls:

Since 1999, at least 2,262 Toyota and Lexus owners have reported to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the media, the courts and to Safety Research & Strategies that their vehicles have accelerated suddenly and unexpectedly in a variety of scenarios. These incidents have resulted in 815 crashes, 341 injuries and, 19 deaths potentially related to sudden unintended acceleration.

In May 2010, the NHTSA updated these statistics to more than 6,200 reports of sudden acceleration in Toyota vehicles from 2000 to mid-May, with these reports including 89 deaths and 57 injuries over the same period.

In the wake of the November 2009 and January 2010 recalls, the U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform held a hearing on 24 February 2010 titled: “Toyota Gas Pedals: Is the Public At Risk?” at which Akio Toyoda, President and CEO of the Toyota Motor Corporation, gave testimony. As part of his testimony, Toyoda issued a widely reported public apology for the accidents experienced by Toyota drivers.

In regard to Toyota’s response to the sudden unintended acceleration reports, the Safety Research & Strategies, Inc. report states that:

Toyota initially blamed customers for improperly installing accessory floor mats and resisted taking widespread action … [however] An accelerator pedal that is slow to return to idle requires repair, but does not cause Sudden Unintended Acceleration.

The agency’s investigations have been too brief and cursory to find other causes. Its decisions to open or close probes, based on shifting statistical bases, have contributed to a continuing safety issue …

… there is ample evidence to suggest that neither Toyota nor NHTSA have identified all of the causes of SUA in Toyota vehicles or all of the vehicles plagued by this problem.

The report then argues that, just as has happened with Boeing, increasingly complicated electronic systems and a failure to fully understand and adequately address the complex human interactions with those systems contributed to the SUA problems:

Absent a mechanical cause, the automaker and the regulators must look more closely at the vehicle control systems, including the electronic throttle control assembly and the associated sensors. Toyota has consistently argued that its electronic throttle control design and failsafe systems are infallible. …

Sudden Unintended Acceleration is a contentious topic in automotive circles. The debate was born in the 1980s, when angry Audi owners, claiming that their vehicles could suddenly accelerate, were crashing their vehicles with alarming frequency. Audi blamed drivers unfamiliar with its vehicles. Drivers could not be persuaded that they had made an error. Five recalls ensued. … The Bowden cable, the linchpin of mechanical throttle designs, is rapidly becoming an obsolete technology. Vehicles are now complicated interfaces where mechanicals systems are controlled by increasingly sophisticated electronics. Any examination of SUA must fully explore the interactions between the two, as well as simpler, easy-to-understand causes. This has not yet been done for the Toyota SUA incidents.

But later inquiries by NASA and the NHTSA did look at these electronic throttle systems, reporting in February 2011 that there were no electronic faults in Toyota cars that would have caused sudden unintended acceleration issues.

However, in October 2013 Toyota very quickly settled a lawsuit after an Oklahoma jury found that Toyota had acted with “reckless disregard.” A Safety Research & Strategies, Inc. article reports on the court case:

What did the jury hear that constituted such a gross neglect of Toyota’s due care obligations? The testimony of two plaintiff’s experts in software design and the design process gives some eye-popping clues. After reviewing Toyota’s software engineering process and the source code for the 2005 Toyota Camry, both concluded that the system was defective and dangerous, riddled with bugs and gaps in its failsafes that led to the root cause of the crash.

… software experts, Phillip Koopman, and Michael Barr, provided fascinating insights into the myriad problems with Toyota’s software development process and its source code – possible bit flips, task deaths that would disable the failsafes, memory corruption, single-point failures, inadequate protections against stack overflow and buffer overflow, single-fault containment regions, thousands of global variables. The list of deficiencies in process and product was lengthy.

Michael Barr, a well-respected embedded software specialist, spent more than 20 months reviewing Toyota’s source code at one of five cubicles in a hotel-sized room, supervised by security guards, who ensured that entrants brought no paper in or out, and wore no belts or watches. Barr testified about the specifics of Toyota’s source code, based on his 800-page report. Phillip Koopman, a Carnegie Mellon University professor in computer engineering, a safety critical embedded systems specialist, authored a textbook, Better Embedded System Software, and performs private industry embedded software design reviews – including in the automotive industry – testified about Toyota’s engineering safety process. Both used a programmer’s derisive term for what they saw: spaghetti code – badly written and badly structured source code. …

Even a Toyota programmer described the engine control application as “spaghetti-like” in an October 2007 document Barr read into his testimony. …

Their testimony explains why it would be near impossible for NHTSA to ever pin an electronic failure on a problem buried in software. NHTSA didn’t even have any software engineers on ODI’s staff during the myriad Toyota UA investigations. They have no real expertise on the complexities that actually underpin all of the safety-critical vehicle functions of today’s cars. It’s as if ODI engineers are investigating with an abacus, a chisel and a stone tablet. One begins to understand the agency’s stubborn doubling, tripling, quadrupaling down on floor mats and old ladies as explanations for UA events.

The next – and at this point in time final – major event in the Toyota recall saga was the U.S. Department of Justice announcement in March 2014 of criminal charges against Toyota Motor Corporation. These charges resulted in Toyota agreeing to pay a record USD $1.3 billion settlement for misleading American consumers. The charges did not consider electronic systems and software, instead focusing on how in 2009 Toyota had claimed that floor mats were the cause of the sudden unintended acceleration while at the same time hiding another problem:

… at the same time it was assuring the public that the “root cause” of unintended acceleration had been “addressed” by the 2009 eight-model floor-mat entrapment recall, TOYOTA was hiding from NHTSA a second cause of unintended acceleration in its vehicles: the sticky pedal. Sticky pedal … resulted from the use of a plastic material inside the pedals that could cause the accelerator pedal to become mechanically stuck in a partially depressed position.

The sudden unintended acceleration issue has since faded from the media spotlight, and it was recently announced that the U.S. Government would be withdrawing support for a proposal that would require all passenger vehicles to have safety systems to prevent unintended acceleration. However, I can’t help but wonder if the sudden unintended acceleration issue will resurface at some point in the future, especially as it’s unclear to what extent Toyota and other manufacturers have satisfactorily addressed concerns in regard to electronic systems and software.

Parallels with Boeing

As has happened with the Boeing crashes, Toyota had released vehicles into the market with increasingly complicated systems that it believed were safe but weren’t, then failed to appropriately respond to the issues drivers of its vehicles were raising, clinging all the while to the mistaken belief that its systems couldn’t go wrong.

Toyota CEO Akio Toyoda has had to publicly apologise for fatal car accidents, just as Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg has recently done in regard to the fatal 737 MAX accidents. Toyota has faced U.S. Department of Justice criminal charges for dark side KM tactics4 and Boeing is currently facing a U.S. Department of Justice criminal investigation for matters that potentially include dark side KM tactics.

This is despite Toyota having pioneered The Toyota Way, a very famous quality framework built on two pillars: continuous improvement and respect for people. The Toyota Way is often lauded by knowledge managers, but as is the case with Boeing’s KM program, The Toyota Way is internally focused to the neglect of the complex external environment and Toyota’s interface with that environment.

Toyota CEO Akio Toyoda confirms this in the testimony he gave to the February 2010 U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform hearing. He states that:

I would like to discuss how we plan to manage quality control as we go forward. Up to now, any decisions on conducting recalls have been made by the Customer Quality Engineering Division at Toyota Motor Corporation in Japan. This division confirms whether there are technical problems and makes a decision on the necessity of a recall. However, reflecting on the issues today, what we lacked was the customers’ perspective.

To make improvements on this, we will make the following changes to the recall decision-making process. When recall decisions are made, a step will be added in the process to ensure that management will make a responsible decision from the perspective of “customer safety first.” To do that, we will devise a system in which customers’ voices around the world will reach our management in a timely manner, and also a system in which each region will be able to make decisions as necessary.

It’s not clear if Toyota has made these changes, and even if it has, the approach described by Toyoda falls short of the approaches recommended for understanding and responding to complexity that I discussed in the second article of the series. Toyoda says only that customer perspectives will be considered by management, rather than Toyota opening up discussion with customers and creating a collaborative environment where good ideas can emerge.

Takata airbag recall

The current and ongoing Takata airbag recall is one of the largest consumer product recalls ever conducted, affecting tens of millions of vehicles worldwide. Takata airbags are very widely used, but long-term exposure to high heat and humidity can cause them to explode when deployed. These explosions have caused injuries and deaths.

Just as has occurred with Boeing and Toyota, Takata is alleged to have failed to respond to early warnings from customers that there were problems with the airbags rupturing, and, just like the CEOs of Boeing and Toyota, Takata CEO Shigehisa Takada has publicly apologised for the defective airbags. Just as Toyota has faced criminal charges and Boeing is currently the subject of a criminal investigation, Takata has had to address criminal charges from the U.S. Department of Justice. Three Takata executives were charged with fabricating test data to mask a fatal airbag defect, a dark side KM tactic, and in response, Takata agreed to plead guilty and pay a $1 billion settlement.

Further, a recommendation from the 2016 report5 of the Independent Takata Corporation Quality Assurance Panel highlights that, just as has occurred with Boeing and Toyota, Takata’s processes have been internally focused to the neglect of the complex external environment and Takata’s interface with that environment. The Panel states that:

Takata should refine its process for identifying quality-related problems … and make better use of the information that it collects … The roles and duties of those employees responsible for responding to externally raised quality issues should be formalized and specific processes should be put in place governing how those teams manage (and elevate, if necessary) potential quality problems when identified. Those processes should put a premium on timely and accurate reporting. Takata should also explore the possibility of engaging in some form of independent in-fleet monitoring and put a system in place that allows the data it collects on product performance to be systematically studied.

A further Panel recommendation highlights that Takata’s decision-making processes haven’t even involved all of the necessary internal stakeholders:

Another of the Panel’s design process-related quality concerns is that manufacturing personnel are often not involved, if they are involved at all, until very late in the design process. In most cases, manufacturing does not get significantly involved until after a product’s design reviews are complete. Moreover, manufacturing personnel do not have any sort of primary approval role in the design review process.

In the wake of the scandal, Takata has filed for bankruptcy and CEO Shigehisa Takada has resigned. This is a spectacular fall from grace for the once highly regarded Takada family, the billionaire founders of Takata.

Cognitive biases

Why are the circumstances of the safety failures of Boeing, Toyota, and Takata so remarkably similar?

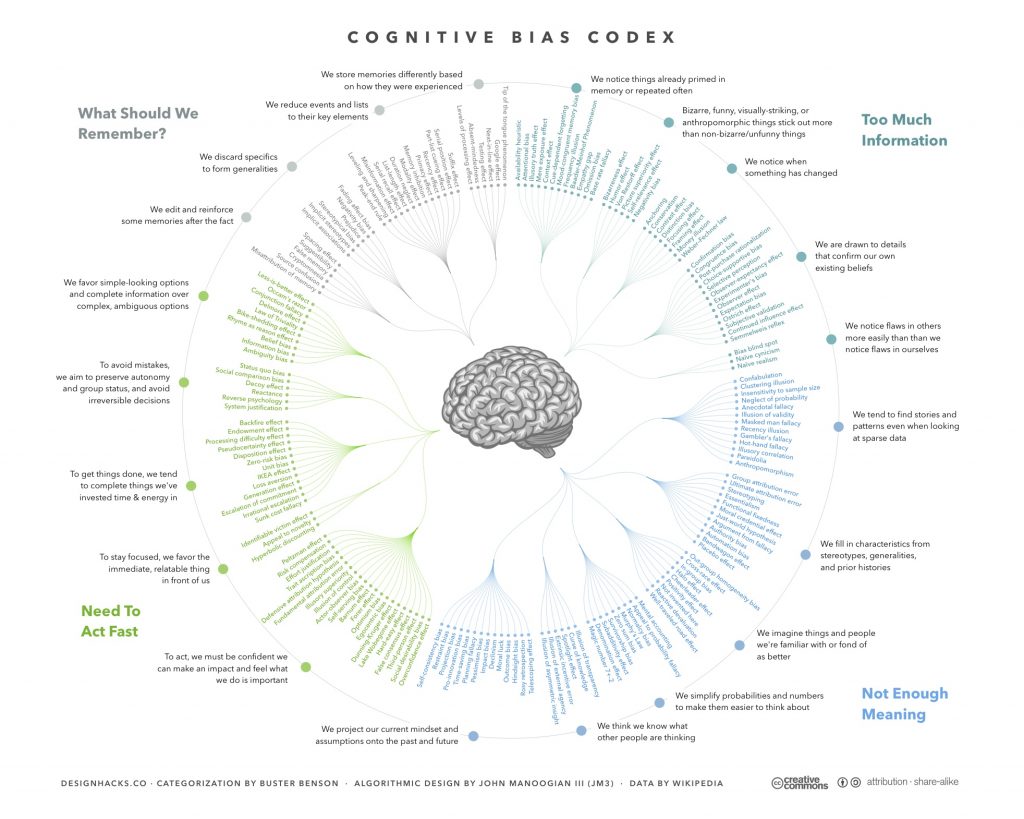

Buster Benson alerts that the way our brains have evolved to deal with fundamental problems that humans face means that we have a wide range of cognitive biases. Our cognitive biases help us to survive in this world, but mean that we don’t see that world rationally. Benson, author of the cognitive bias cheat sheet (represented in the codex in Figure 1), advises that we have developed unique biased mental strategies that we use for very specific reasons.

The biased mental strategies can be grouped under the four general mental problems that they are trying to address: information overload, lack of meaning, the need to act fast, and how to know what needs to be remembered for later:

- Information overload sucks, so we aggressively filter. Noise becomes signal.

- Lack of meaning is confusing, so we fill in the gaps. Signal becomes a story.

- Need to act fast lest we lose our chance, so we jump to conclusions. Stories become decisions.

- This isn’t getting easier, so we try to remember the important bits. Decisions inform our mental models of the world.

Further compounding the situation, our solutions to these problems also have problems:

- We don’t see everything. Some of the information we filter out is actually useful and important.

- Our search for meaning can conjure illusions. We sometimes imagine details that were filled in by our assumptions, and construct meaning and stories that aren’t really there.

- Quick decisions can be seriously flawed. Some of the quick reactions and decisions we jump to are unfair, self-serving, and counter-productive.

- Our memory reinforces errors. Some of the stuff we remember for later just makes all of the above systems more biased, and more damaging to our thought processes.

These cognitive biases can be seen in the initial rejection of information that was contrary to the strongly held beliefs by Boeing, Toyota, and Takata that there couldn’t be anything wrong with their systems, and in the dark side KM tactics that each used to try to maintain this position.

For example, in regard to Takata, Wharton University management professor John Paul MacDuffie states that:

Many of Takata’s competitors decided not to use ammonium nitrate because of the risks it involved. However, Takata was confident about its engineering and manufacturing expertise and in being able to tackle any quality problems that arose and make improvements. Therein lies the genesis of Takata’s problems, including possibly leading it to manipulating test data. You have the challenge to that engineering culture and confidence as well as the risk of embarrassment and criminal prosecution when the problems begin to emerge. It’s not surprising that companies want to block out any evidence that these deeply held beliefs in the rightness of what they were doing were wrong, as well as wanting to hide wrongdoing.

Cognitive biases impact directly on the complex interface of technology and people because they affect core aspects of complexity including interconnectedness and interdependence, feedback processes, nonlinearity, initial conditions, adaptive agents, self-organisation, and co-evolution, as well as lesser discussed traits of complex systems.

This means that internally-focused linear quality improvement and knowledge management programs can only ever be of the limited success evident in the cases of Boeing, Toyota, and Takata. However, a different approach to knowledge management offers a pathway forward, and some highly innovative organisations are already demonstrating great success with this approach.

Next and final part (part 4): Embracing a different approach to knowledge management.

A complex system can only be understood by understanding the small particular parts of day to day interaction. In order to do that, we have to engage people.

Header image source: Angie Johnston on Pixabay, Public Domain.

References:

- NHTSA (2017). 2017 NHTSA Recall Annual Report. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) ↩

- Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0. ↩

- Kane, S., Liberman, E., DiViesti, T., & Click, F. (2010). Toyota sudden unintended acceleration. Safety Research & Strategies. ↩

- Alter, S. (2006, January). Goals and tactics on the dark side of knowledge management. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’06) (Vol. 7, pp. 144a-144a). IEEE. ↩

- Independent Takata Corporation Quality Assurance Panel (2016). Ensuring Quality Across the Board. The Report of the Independent Takata Corporation Quality Assurance Panel. ↩

Fascinating article, Bruce! I’m looking forward to part 4.

Many thanks for your feedback Edgar, much appreciated!