Getting to the heart of the problems with Boeing, Takata, and Toyota (part 2): Current approaches to KM aren’t adequately addressing complexity

This four-part series looks at what recent fatal Boeing 737 MAX aircraft crashes have in common with the Toyota and Takata automotive recall scandals, and proposes a solution.

In the first article of this series, I look at medicine’s aspirations to be more like aviation in how it manages the serious problems that are arising at the complex interface between people and technology. Aviation does have a much better safety record than healthcare, and research shows that there are some safety lessons that medicine can learn from aviation. However, aviation and medicine have also been found to have a number of quite distinctive features, and, as I revealed, the recent shocking fatal crashes of new Boeing 737 MAX aircraft show that aviation really isn’t the role model that medicine thought it was.

This is because the 737 MAX crashes alert to failures in regard to addressing the “situational awareness knowledge challenge”. The long-standing situational awareness knowledge challenge is the difficulty that aircraft manufacturers face in providing the right amount of information to aircrew. At busy times during a flight, such as takeoff and landing or when unexpected incidents occur, an aircraft cockpit can become a place of extreme stress where the aircrew needs to attempt to respond very quickly to a short series of multiple events. In this pressure cooker environment, both a lack of information and too much information are a problem. The ever-increasing complexity of aircraft systems over time is contributing to the persistence of this situational awareness knowledge challenge.

In the case of the ill-fated 737 MAX, Boeing didn’t achieve the right balance in the situational awareness knowledge challenge because it failed to tell pilots about a new system called the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS). Further, Boeing failed to respond to the criticism of pilots who pointed out that it hadn’t got the balance right.

In this second article of the series, I look at what this means for knowledge management (KM) at Boeing.

Inadequacies in Boeing’s KM?

How could Boeing fail to transfer adequate knowledge about the MCAS to pilots and then fail to adequately respond to the knowledge of pilots when the company has a much-lauded knowledge management (KM) program, as shown in the cover story of the October 2007 issue of the company’s Frontiers magazine (Figure 1)?

I suggest that there are three reasons for this:

- Boeing’s KM program is internally focused, to the neglect of external knowledge flows between Boeing and the users of its products, being the many pilots in the many airlines around the world

- Boeing’s KM program lacks mechanisms to adequately deal with the complexity that occurs at the interface between its products and the users of its products

- Boeing’s KM program doesn’t acknowledge or address the dark side of KM.

As I stated in the previous article, it doesn’t appear that Boeing set out to deliberately hide information about the MCAS from pilots, but rather that serious errors of judgement were made in regard to what Boeing thought aircrew did and didn’t need to know. Addressing the knowledge needs of aircrew – who are the primary users of Boeing’s products – is not a focus of Boeing’s KM program. Neither is capturing the knowledge of aircrew and using it to innovate and improve Boeing’s aircraft. Rather, the focus of the Boeing’s KM program is its employees, with the Frontiers cover story stating that “At Boeing, knowledge management is made up of a comprehensive system of processes, tools, methods and techniques that enable employees to capture and share information effectively.”

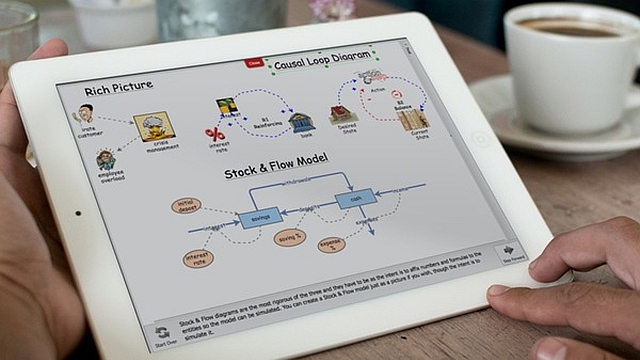

Similarly, the methods and tools used in Boeing’s KM program aren’t those recommended for understanding and responding to complexity. In their highly-cited Harvard Business Review article A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making1 Dave Snowden and Mary E. Boone advise that the following tools can be used to manage in a complex context:

- Open up the discussion. Complex contexts require more interactive communication than any of the other domains.

- Set barriers. Barriers limit or delineate behavior. Once the barriers are set, the system can self-regulate within those boundaries.

- Stimulate attractors. Attractors are phenomena that arise when small stimuli and probes (whether from leaders or others) resonate with people.

- Encourage dissent and diversity. Dissent and formal debate are valuable communication assets in complex contexts because they encourage the emergence of well-forged patterns and ideas.

- Manage starting conditions and monitor for emergence. Because outcomes are unpredictable in a complex context, leaders need to focus on creating an environment from which good things can emerge, rather than trying to bring about predetermined results and possibly missing opportunities that arise unexpectedly.

While the communities of practice used in Boeing’s KM program may assist in opening up discussion, they are internally focused and not designed to effectively enable the other tools recommended by Snowden and Boone. Other approaches, for example co-creation and collaborative learning, are much more effective in this regard.

Further, the errors of judgement made by Boeing in deciding what aircrew did and didn’t need to know are part of a larger series of human errors made as the company rushed to get the 737 MAX into the air in the fastest and most cost-effective way, in response to the ever-present rivalry of major competitor Airbus. As part of this series of errors, Boeing also failed to provide adequate information to the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and the FAA stands accused of failing to provide adequate oversight. Highlighting the seriousness of these issues, prosecutors from the U.S. Department of Justice have reportedly launched a probe into the way the FAA regulated Boeing.

The “failure to distribute important knowledge that is needed” is one of the tactics on the “dark side” of KM, a topic that I discussed in a recent article2. Boeing’s KM program doesn’t address the dark side of KM, which is understandable given that the KM academic literature is silent in regard to what should be done about this issue. Unfortunately KM discussions typically take on a utopian tone, where knowledge is seen as something that people will want to manage with the best of intentions, despite numerous examples of major companies who have engaged in dark side KM, for example Enron3 where there were also knowledge transfer failures.

Recent news reports support the view that Boeing has engaged in dark side KM. These reports state that in addition to the 737 MAX investigation, the U.S. Department of Justice has now “subpoenaed records from Boeing relating to the production of the 787 Dreamliner in South Carolina, where there have been allegations of shoddy work.” The 787 Dreamliner is Boeing’s other major new aircraft. While it still doesn’t appear that Boeing set out to deliberately do the wrong thing, the competitive pressures to quickly bring new aircraft to the market could have meant that some managers or staff felt compelled to cut corners, bringing about a dark side KM culture that has potentially undermined Boeing’s much-lauded internal KM efforts.

Next part (part 3): Toyota, Takata, and cognitive biases.

Unfortunately it’s not just aviation and medicine that are experiencing life-threatening problems at the complex interface between technology and people. There are disturbing parallels between the current situation with Boeing and two significant recent scandals involving the automotive industry – the Toyota and Takata recalls. Cognitive biases play a role in this.

Header image source: Adapted from Knowledge by Nick Youngson on Alpha Stock Images which is licenced by CC BY-SA 3.0.

References:

- Snowden, D. J., & Boone, M. E. (2007). A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review, 85(11), 68. ↩

- Alter, S. (2006). Goals and tactics on the dark side of knowledge management. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’06) (Vol. 7, pp. 144a-144a). IEEE. ↩

- Seeger, M. W., & Ulmer, R. R. (2003). Explaining Enron: Communication and responsible leadership. Management Communication Quarterly, 17(1), 58-84. ↩