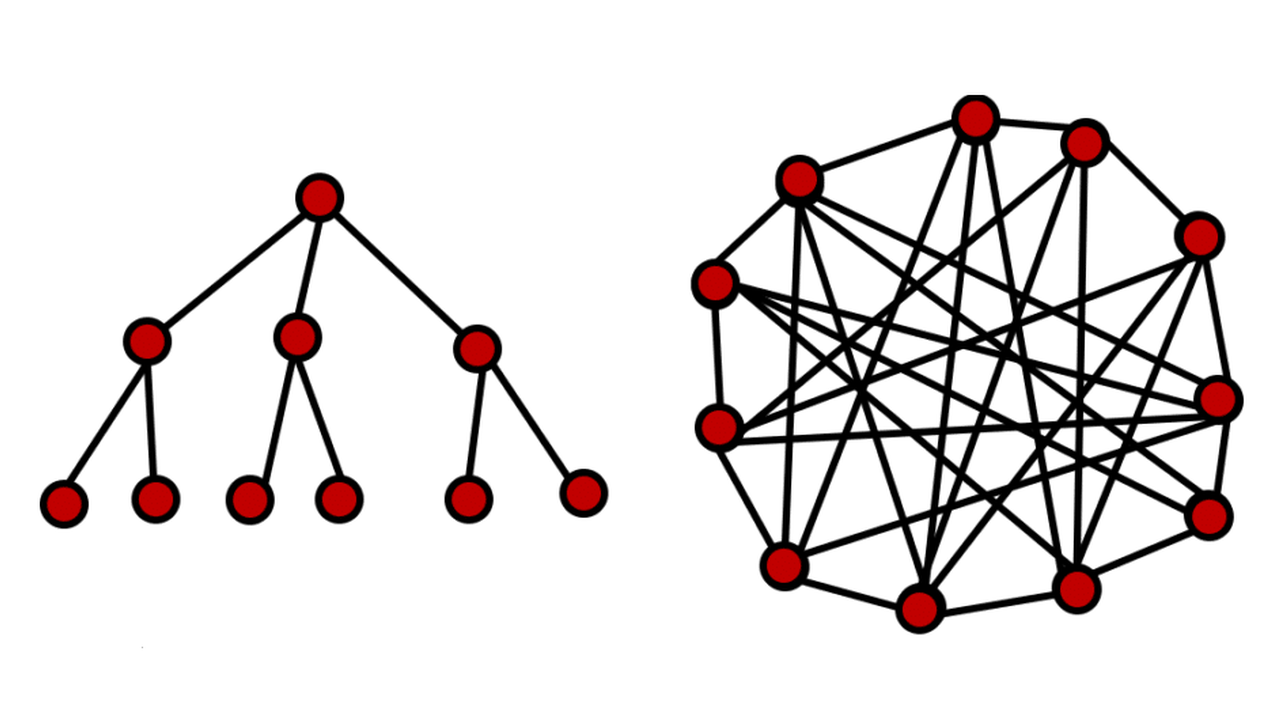

Top-down vs. collaborative consensus: using the most appropriate approach for the decision-making level

In a recent article, RealKM’s Stephen Bounds explores the contentions around command and control approaches to management vs. alternative management methods that seek to empower employees and engage them in consensus building.

In his article, Stephen expresses the view that:

it is entirely possible to encourage and respect decentralised knowledge and problem solving while retaining an overriding purpose and command structure.

Different change strategies at different levels

A 2015 paper1 supports Stephen’s view. The paper puts forward five different change strategies that have an alignment with the different planning approaches put forward by Stephen. The five different change strategies are:

- Directive strategy – the manager uses his authority and imposes change with little or no involvement of other people.

- Expert strategy – usually involves expertise to manage and solve technical problems that result from the change.

- Negotiating strategy – manager shows willingness to negotiate and bargain in order to effect change with timely adjustments and concessions.

- Educative strategy – when the manager plans to change peoples’ values and beliefs.

- Participative strategy – when the manager stresses the full involvement of all of those involved and affected by the anticipated changes.

In the case study discussed in the 2015 paper, a top-down decision was made, which represents the “directive strategy” put forward in the paper and the “blueprint planning” approach put forward by Stephen in his article.

As the 2015 paper alerts, the directive strategy is often met with resistance because people aren’t given enough time to be able to assimilate the changes. However, the paper authors advise that while there was initial uncertainty, the expert strategy, negotiating strategy, and educative strategy were applied later to help smooth the change. In this way, the directive strategy was turned into an advantage that facilitated the rapid implementation of change.

This highlights the critical need to consider what is the most appropriate strategy/approach for particular levels of a decision-making structure/process. Use of the directive strategy can be unavoidable or even necessary at some levels of the structure/process. But similarly, if successful outcomes overall are to be achieved, then other strategies will be more desirable at other levels of the structure/process than the directive strategy.

Change strategy case studies

Further case studies of both effective and ineffective change clearly demonstrate the critical need to consider what is the most appropriate strategy/approach for particular levels of a decision-making structure/process.

Helidon Hills project

One case study is the Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills Project, which I’ve previously discussed in RealKM Magazine. The Helidon Hills project was lauded for its effective community engagement and consensus building – the negotiating and participative strategies described above – but there was also a directive strategy aspect to the decision-making. This was that the nature conservation and cultural heritage values of the Helidon Hills area must be protected as a non-negotiable given, based on studies and assessments by ecological scientists and cultural heritage experts in consultation with First Nations representatives. So that the directive strategy was informed by the expert strategy.

There’s a very sound reason for this. Environmental management in Australia is extremely poor, with the country having one of the world’s worst biodiversity conservation records (as well as a shocking record of Indigenous heritage destruction). This conservation record stands in stark contrast to other western countries such as the United States and Canada. As the Interim Report from the Parliament of Australia Senate inquiry into Australia’s faunal extinction crisis states2:

The extent of the decline means that Australia has one of the world’s worst records for the extinction and lack of protection for threatened fauna and is ranked second (after Indonesia) in the world for ongoing biodiversity loss. Submitters cited reports indicating that more than 10 per cent of endemic terrestrial land mammal species have become extinct over the last 200 years, which represents 50 per cent of the global mammal extinctions during that period. In comparison, only one native land mammal from continental North America has become extinct since European settlement.

The Helidon Hills is recognised as an area of very high nature conservation significance. It is one of the largest areas of mostly continuous bushland left in the southeastern region of the Australian state of Queensland, and has a large number of rare and threatened flora and fauna species. This includes a large number of species that are found only in this area, for example Eucalyptus helidonica.

Protecting the conservation values of areas such as the Helidon Hills is essential if Australia is to halt and then ultimately reverse its worsening biodiversity crisis. So this Helidon Hills project outcome was a non-negotiable given, and clearly stated from the beginning of the project. Rather, the community engagement and consensus building focused on how this would be done in the context of the complex range of often conflicting land use and land management objectives of the diverse array of stakeholders with an interest in the area.

The directed “non-negotiables” or “givens” can also be described as “barriers” or “boundaries.” For example, one of the tools for managing in a complex context put forward by Dave Snowden and Mary E. Boone in their highly-cited Harvard Business Review article3 “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making” is:

Set barriers. Barriers limit or delineate behavior. Once the barriers are set, the system can self-regulate within those boundaries.

Loess Plateau recovery projects

I’ve also observed the effective application of a similar approach to achieve successful large-scale landscape recovery.

The Loess Plateau in China covers a massive area of 640,000 km2, extending across almost all of the provinces of Shaanxi and Shanxi and into parts of Henan, Gansu, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia4. Significant in the history of Chinese civilization, the fragile Loess Plateau landform is highly erodible, and centuries of overuse and overgrazing had led to one of the highest erosion rates in the world and widespread poverty.

Recognising this, the Chinese Government has implemented major recovery projects with the support of the World Bank. The directive and expert strategy decision-making aspects of these projects has included grazing controls and strict limits on cropping on the Loess landform. Such measures were essential to quickly halt further decline, but could have very negatively impacted many of the more than 50 million people who make the Loess Plateau their home. However, the other strategies – negotiating strategy, educative strategy, and participative strategy – have been successfully used to engage and empower communities in implementing sustainable farming practices and alternative land uses.

The impacts of this have been profound, achieving not only an astounding level of landscape recovery, but also a doubling of incomes, lifting hundreds of thousands of people out of poverty. I’ve been able to experience this directly myself, spending a few months living with friends in their village in the Loess recovery area in Shanxi province. Destructive grazing no longer occurs, and cropping is limited to small family plots (Figure 1). I also saw that thousands of trees had been planted, particularly higher up in the landscape. Overall, the remedial measures have resulted in stabilization of the landscape, with a dramatic reduction in erosion and a significant increase in biodiversity. The village is also thriving, as evidenced by the very positive community spirit I observed in my time living in the village, which included participating in preparations for two of the annual village Lantern Festival galas (Figure 2).

Murray-Darling Basin Plan

Unfortunately, though, I’ve also observed the opposite here in Australia. Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin is also a significant rural landscape that has experienced severe degradation, but as I’ve previously written in RealKM Magazine, a woeful approach to community and stakeholder engagement has triggered widespread opposition to the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, which has in turn constrained actions to reverse ecological decline.

The Murray-Darling Basin has suffered an environmental catastrophe. This means that Australia’s Federal and Murray-Darling Basin state governments should have deployed the directive and expert strategies to immediately halt damaging water and land management activities. They should have then used the negotiating, educative, and participative strategies to develop and implement sustainable farming practices that also have economic benefits. Sadly, none of this has been effectively done.

Not using the directive and expert strategies at the highest level of the decision-making structure to halt environmentally destructive activities has meant that ecological collapse has continued to occur in the Murray-Darling Basin. It has also meant that many in the environment sector have little confidence in the Murray-Darling Basin Plan.

Similarly, using the directive strategy at other levels of decision-making structure rather than the negotiating, educative, and participative strategies has meant that many in the farming and indigenous sectors have little confidence in the Murray-Darling Basin Plan.

Failing to effectively engage farming and indigenous communities in the preparation and implementation of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan is also indicative of low-quality democracy. As Dr Nicolas Pirsoul and Maria Armoudian from the University of Auckland write in The Conversation in regard to water management in New Zealand:

In a liberal representative democracy such as New Zealand’s, political decisions result from elections. The three-yearly electoral cycle, however, tends to encourage symbolic politics geared towards winning votes rather than generating long-term solutions to complex problems like freshwater quality …

With no real mechanism for public participation beyond the next general election or non-binding public consultation and submission processes, New Zealanders are left largely powerless …

we argue that by first improving our democratic system we can then begin to solve environmental problems such as freshwater quality …

Effective alternatives already exist but these require challenging the assumption that democracy is synonymous with elections.

The first step would be to reinvigorate democracy at the local level.

A newly published draft paper5 from Australia’s Productivity Commission gives some hope that the tide may finally be starting to turn, but more still needs to be done. Supporting my views, the Productivity Commission draft paper states that:

implementation of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan illustrates very clearly the consequences of poorly executed community engagement.

The draft paper then puts forward the IAP2 community engagement spectrum as a basis for improved engagement. There is some alignment between the IAP2 spectrum and four of the five strategies discussed above – expert strategy, negotiating strategy, educative strategy, and participative strategy.

However, the draft paper doesn’t acknowledge the need for the directive strategy, or how this strategy and the different levels of engagement in the IAP2 community engagement spectrum could be more effectively applied by aligning them with different levels in the decision-making structure for the Murray-Darling Basin. I hope that this could be a next step in progressing the recommendations of the draft paper.

Countering authoritarian populism

Advocating the use of the directive change strategy at higher levels of a decision-making structure/process may at first glance appear to be an authoritarian approach. However, the opposite is true.

The adjective “authoritarian” and associated noun “authoritarianism” can be defined6 as “Favouring or enforcing strict obedience to authority at the expense of personal freedom.”

The first point to note is that the leaders of all governments and all organisations across the world use the directive strategy. Governments worldwide use the directive strategy to implement laws and regulations with the aim of creating overall benefits for society. Similarly, managers worldwide use the directive strategy to implement decisions aimed at the best organisational performance and outcomes. So the use of the directive strategy is not in itself “authoritarian.”

The second point is that while the label “authoritarian” is often directed at dictatorships or one-party governments, all governments can be authoritarian (or not), including western democracies. Indeed, researchers have been increasingly documenting7 the accelerating rise of “authoritarian populism” in western democracies:

to be ‘authoritarian’ is to seek social homogeneity through coercion. ‘Populism’ is defining a section of the population as truly and rightfully ‘the people’ and aligning with this section against a different group identified as elites. Together, ‘authoritarian populism’ refers to the pitting of ‘the people’ against ‘elites’ in order to have the power to drive out, wipe out, or otherwise dominate Others who are not ‘the people.’ Generally, this involves social movements fuelled by prejudice and led by charismatic leaders that seek to increase governmental force to combat difference. It is commonplace for governments under the direction of authoritarian populists to condense and centralize authority, so that more power rests in the hands of fewer people.

Former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has described many conservative politicians in Australia as being “authoritarian populist.” In an article in The Conversation, Carol Johnson, an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Adelaide, extends this conclusion to the current Australian Government of Prime Minister Scott Morrison. This aligns with my comments above in regard to Australia’s low-quality democracy. Johnson states that:

The populist tinge to Morrison’s politics was obvious during the 2019 election campaign …

Morrison’s election persona of “ScoMo”, the warm and friendly daggy dad from the suburbs, might not seem authoritarian. However, even then, there were authoritarian tendencies creeping in to his populism. This is not just in his attitudes to asylum seekers, but also to Australians. For example, Morrison’s slogan: “A fair go for those who have a go” implied that some welfare recipients didn’t deserve the benefits they were getting.

Indeed, the Morrison government’s authoritarian policy agenda also has a punitive element that has become more evident since the election.

Evidence for the punitive element of the Australian Government’s authoritarian populism includes the draconian robodebt welfare debt recovery scheme, which was later found to be unlawful, and threatening Australians who were seeking to escape the COVID-19 crisis in India with five years jail, a $66,000 fine, or both.

In the change strategy case studies above, the approaches taken by Australia’s Federal and Murray-Darling Basin state governments in regard to the Murray-Darling Basin Plan have also been authoritarian, using the directive change strategy to impose restrictive constraints on rural landholders and communities without adequate consideration of their economic and social rights and freedoms (Figure 3). In contrast, the approach I took in regard to the Helidon Hills project and that the Chinese Government has taken in regard to the Loess Plateau projects have respected people’s economic and social rights and freedoms by only using the directive strategy where appropriate.

This means that using the most appropriate strategy/approach for particular levels of a decision-making structure/process can actually help to counter authoritarianism. Research supports this conclusion. For example, a paper8 published in the Journal of Rural Studies documents how rural decline has contributed to the rise of authoritarian populism in the United States. In a second example, a paper9 published in German Law Journal looks at the rise of authoritarian populism in Europe. The author advises that:

In order to defuse the steady rise of populism in Europe …. What counts this time are sensible economic, social and environmental policies promising to improve daily lives of European citizens.

The change strategy case studies above clearly show that this can be readily achieved by using the directive and expert strategies to establish scientifically sound environmental policies that quickly and effectively halt destructive activities, and then the negotiating, educative, and participative strategies to engage communities in establishing new economic and social policies that improve people’s lives.

Header image source: Stack Exchange, CC BY-SA 3.0.

References:

- Hanan M. Al-Kadri, Ibrahim A. Al Alwan, Mohamed S. Al-Moamary, Youssef A. Al Eissa & Bandar A. Al Knawy (2015). From Clinical Center to Academic Institution: An Example of How to Bring About Educational Change. Health Professions Education, 1, 4-11. ↩

- Commonwealth of Australia (2019). Australia’s faunal extinction crisis, Interim report. Senate Environment and Communications References Committee. ↩

- Snowden, D. J., & Boone, M. E. (2007). A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review, 85(11), 68. ↩

- Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0. ↩

- Productivity Commission (2021). Community engagement, Supporting Paper J to National Water Reform 2020, Draft Report, Canberra. ↩

- Lexico.com. ↩

- Morelock, J. (ed) (2018). Critical theory and authoritarian populism. University of Westminster Press. ↩

- Edelman, M. (2019). Hollowed out Heartland, USA: How capital sacrificed communities and paved the way for authoritarian populism. Journal of Rural Studies. DOI: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.10.045 ↩

- Bugaric, B. (2019). The two faces of populism: Between authoritarian and democratic populism. German Law Journal, 20(3), 390-400. ↩

Also published on Medium.