KM standard controversy: lessons from the environment sector in regard to open, inclusive, participatory processes

This article is part of a series of articles on the new international knowledge management (KM) standard, ISO 30401 Knowledge management systems – Requirements, and also part of a series of articles on stakeholder and community engagement.

The draft of the new international knowledge management (KM) standard, ISO 30401 Knowledge management systems – Requirements, was released for public review and comment in November last year.

Soon after the release of the draft, David Griffiths, the founder of UK-based knowledge management consulting company K3-Cubed, wrote a blog post strongly critical of the draft standard and its development process. The post was also shared on Facebook by Dave Snowden, who said that he endorsed most of what David Griffiths had said. A number of other people in the KM community also then expressed similar concerns.

In his post, David Griffiths expresses concerns about “the limited variety of KM experts engaged in [the standard development] … process,” asking:

… how can anyone possibly claim to take a holistic view when the committee has constrained the view by failing to involve the spectrum of Knowledge Management stakeholders required to develop such a view … ?

I subsequently wrote an article in which I also endorse much of what David has said, stating that I consider the ISO standards development process to run completely counter to everything I’ve learned about open collaborative policy and strategy development through many years of working with diverse communities. I expressed the view that it’s actually rather oxymoronic that the development process for an important knowledge management standard has not involved the widest diversity of relevant knowledge.

While agreeing with David’s criticism of the standard development process, I disagreed with another aspect of his post – his strident criticism of a number of the KM professionals involved in the development process. In response, I advised that we need to “play the ball, and not the man.” That is, if a process ends up biased, then we need to look at the design and conduct of the process, and not at how particular people have approached the process.

It is the design and conduct of the ISO 30401 draft KM standard development process that I will further critique in this article, drawing on my experiences of the good, the bad, and the ugly of planning processes in the environment sector. I worked in this sector for over 20 years, with a primary focus on facilitating the knowledge contributions of researchers, the community, and other stakeholders to planning processes.

This article discusses only the KM standard development process, with the contents of the draft standard having been addressed by Stephen Bounds in a previous article.

How does the KM standard process rate in the participation spectrum?

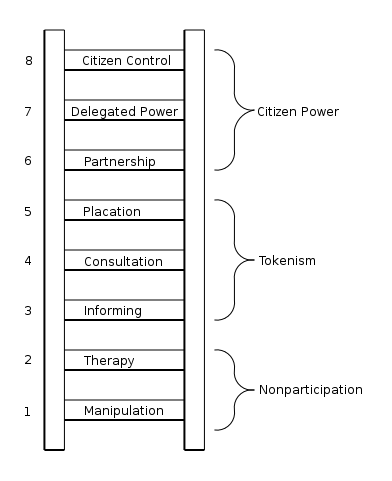

Way back in 1969, Sherry R. Arnstein published her highly influential paper A Ladder Of Citizen Participation1. She describes eight rungs on the ladder of citizen participation (Figure 1), ranging from a low level of participation (rung 1) through to a high level (rung 8).

The eight rungs are:

- MANIPULATION. In the name of citizen participation, people are placed on rubberstamp advisory committees or advisory boards for the express purpose of “educating” them or engineering their support. Instead of genuine citizen participation, the bottom rung of the ladder signifies the distortion of participation into a public relations vehicle by powerholders.

- THERAPY. In some respects group therapy, masked as citizen participation, should be on the lowest rung of the ladder because it is both dishonest and arrogant. Its administrators – mental health experts from social workers to psychiatrists – assume that powerlessness is synonymous with mental illness. On this assumption, under a masquerade of involving citizens in planning, the experts subject the citizens to clinical group therapy.

- INFORMING. Informing citizens of their rights, responsibilities, and options can be the most important first step toward legitimate citizen participation. However, too frequently the emphasis is placed on a one-way flow of information – from officials to citizens – with no channel provided for feedback and no power for negotiation. Under these conditions, particularly when information is provided at a late stage in planning, people have little opportunity to influence the program designed “for their benefit.”

- CONSULTATION. Inviting citizens’ opinions, like informing them, can be a legitimate step toward their full participation. But if consulting them is not combined with other modes of participation, this rung of the ladder is still a sham since it offers no assurance that citizen concerns and ideas will be taken into account … When powerholders restrict the input of citizens’ ideas solely to this level, participation remains just a window-dressing ritual.

- PLACATION. It is at this level that citizens begin to have some degree of influence though tokenism is still apparent. An example of placation strategy is to place a few handpicked “worthy” poor on boards of Community Action Agencies or on public bodies like the board of education, police commission, or housing authority. If they are not accountable to a constituency in the community and if the traditional power elite hold the majority of seats, the have-nots can be easily outvoted and outfoxed.

- PARTNERSHIP. At this rung of the ladder, power is in fact redistributed through negotiation between citizens and powerholders. They agree to share planning and decision-making responsibilities through such structures as joint policy boards, planning committees and mechanisms for resolving impasses. After the groundrules have been established through some form of give-and-take, they are not subject to unilateral change.

- DELEGATED POWER. At this level, the ladder has been scaled to the point where citizens hold the significant cards to assure accountability of the program to them. To resolve differences, powerholders need to start the bargaining process rather than respond to pressure from the other end.

- CITIZEN CONTROL. People are simply demanding that degree of power (or control) which guarantees that participants or residents can govern a program or an institution, be in full charge of policy and managerial aspects, and be able to negotiate the conditions under which “outsiders” may change them.

The ISO 30401 draft KM standard development process has involved a closed group of KM experts – the powerholders in the process – preparing a draft plan behind closed doors and then releasing it for public review. This aligns with the ‘consultation’ rung in Arnstein’s ladder, meaning that public involvement in the ISO 30401 draft KM standard development process was just tokenism, and as Arnstein advised above, “a sham.”

So it’s not at all surprising that strong concerns have been raised about the process. As Arnstein alerts, “There is a critical difference between going through the empty ritual of participation and having the real power needed to affect the outcome of the process.”

Because they don’t adequately involve the full range of stakeholders, planning processes that align with the lower rungs on Arnstein’s ladder carry a serious risk of long-term failure. Let’s look at lessons in this regard from the good, the bad, and the ugly of some planning processes in the environment sector. But I’ll explore them in reverse, beginning with the ugly and ending on a positive note with the good.

The ugly: The Murray-Darling Basin Plan

Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation has been around long enough for everyone leading change processes to not only be well aware of it, but to be actively applying it. And plenty of other evidence has emerged since to support Arnstein’s analysis. Let’s look at some of that evidence in the context of an environmental planning process with disturbing similarities to the ISO 30401 draft KM standard development process.

This environmental planning process is Australia’s development of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, which clearly demonstrates the long-term damage that can be caused by planning processes that are just tokenism. Just as the release of the draft KM standard triggered a backlash from people concerned that the full range of views has not been canvassed, the 2010 release of the guide to the Murray-Darling Basin Plan triggered a backlash from farming communities concerned that their views were not adequately considered. In the case of the guide to the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, this triggered angry protests, including confronting scenes of copies of the guide being burnt, as shown in the header image to this article.

The Murray-Darling Basin Plan spans four Australian states and the Australian Capital Territory, and is home to half of Australia’s irrigated agriculture, making it highly significant to the Australian economy. Fluctuating water availability, increased agricultural production, ecological decline and a century of poor cooperation between the six governments responsible for the Basin has created an environmental management crisis2. Through the Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) the Murray-Darling Basin Plan has been developed with the aim of addressing cross-border issues to achieve a sustainable management outcome.

The establishment of the MDBA is the latest governance arrangement in many years of attempts to address the jurisdictional complexities of water management in the Murray-Darling Basin3, which has been described as a “wicked water problem” 4. Harding, Hendriks, and Faruqi advise that many environmental issues can be described as wicked problems, where complex interconnected ecological and social factors and uncertain contexts and boundaries make the issues very difficult to resolve 5.

Hendricks discusses the wicked problem of elite and expert knowledge in governance for sustainability – what she describes as a technocratic approach – and recommends that governance for sustainability be made more inclusive. However, Daniell finds that despite having stated principles for inclusive stakeholder engagement, the MDBA took a technocratic centralised approach in the development of the Basin Plan, and that this contributed to the community backlash6. In taking this approach, the MDBA has not successfully fulfilled the role of a change agent, which Recklies describes as needing to include the ability to involve everyone affected so that there is commitment and support7.

Harding, Hendriks, and Faruqi state that participation processes for environmental decision-making must be effective and appropriate, with higher levels of participation for issues that are more complex or controversial8. With water management in the Murray-Darling Basin identified as a wicked problem, participation processes should desirably have been at the ‘citizen power’ end of Arnstein’s ladder. However, both farmers and Indigenous communities felt excluded by the Basin Plan process.

In describing the participatory processes that they experienced, the National Farmers’ Federation states that “telling people about the process and seeking their views is not the same thing as engaging communities in its development from the start and truly considering their views.”

Weir explores the narratives of the Indigenous people of the Murray-Darling Basin, finding that they have felt ignored and marginalised by participation processes throughout the entire century of government attempts to find solutions to the management of the Basin9. She documents how the elders of an Aboriginal nation became so frustrated that they chose to leave an inappropriate and ineffective process rather than “legitimise its decisions through participation.”

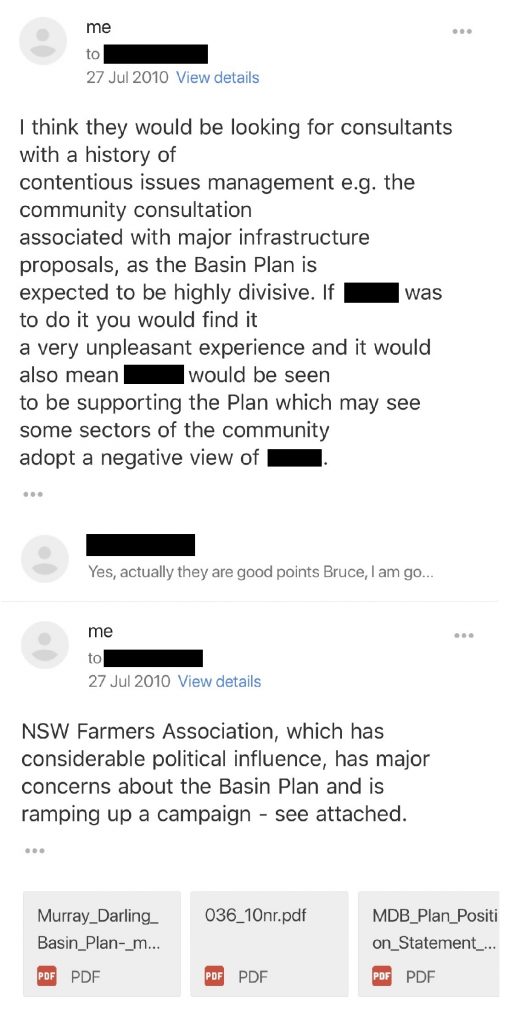

The MDBA’s navel-gazing was so pronounced that they were apparently completely oblivious to the obvious signs of serious stakeholder concern in the lead-up to the release of the Guide to the Murray-Darling Basin Plan. Some of my colleagues had actually approached me at the time seeking my thoughts in regard to their organisation tendering for a MDBA facilitation consultancy addressing “Stakeholder engagement activities … in relation to the Guide to the Proposed Murray-Darling Basin Plan and the Proposed Basin Plan”. In email replies to them (Figure 2), I advised against tendering on the basis of serious concerns that I had seen being expressed on the NSW Farmers Association website. The NSW Farmers Association is a peak representative and lobby group for the rural sector in the State of New South Wales (NSW).

I had attached three documents from the NSW Farmers Association website to my emails: a media release, position statement, and briefing note. It was blatantly obvious from these documents that the NSW Farmers Association was deeply concerned about inadequate involvement in the Murray-Darling Basin Plan development process.

For example, in the media release they state that:

The NSW Farmers’ Association says farmers and regional communities appear to have been effectively shut out of the discussion about the Murray Darling Basin Plan, with potentially devastating results

And in the position statement they advise that:

The Association believes that the current planning process is fundamentally flawed. A sustainable outcome for the Basin demands … A collaborative planning process that engages local expertise and the farm sector at valley scale in a process of optimising water allocation

At the time of this MDBA tender being announced, I was managing another major Australian river recovery program. That program, the Hawkesbury-Nepean River Recovery Program (HNRRP), had established a successful partnership with stakeholders. Contributing to this were the initial arrangements (developed by others before I was engaged), the program management approach I used, and the highly effective relationship building activities of the participating agencies.

As part of all of the work I do, I actively horizon scan so I can be aware of potential threats and opportunities and plan accordingly. For the HNRRP, this included actively monitoring the communications of rural organisations, including the NSW Farmers Association. Horizon scanning helps me to anticipate and respond to what could otherwise be “Black Swan” events.

In my emails to my colleagues, I had given MDBA the benefit of the doubt, thinking that they had belatedly become aware of concerns about the Basin Plan and were seeking to address the situation. Even I could not see just how far away MDBA was from an effective participatory process.

In the wake of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan backlash, MDBA chairman Mike Taylor resigned, urging the Australian Government to “reconsider the next phase” of the plan. But once people have lost confidence in a planning process, it’s very difficult for them to ever again trust the process or the organisations leading it. They would understandably have the mindset that it’s only a fool that makes the same mistake twice. Ever since the confronting images of people burning the guide to the Basin Plan were splashed across the media in 2010, the Basin Plan process has struggled to gain acceptance. In the absence of an agreed plan, stakeholders have just acted in their own interests. Most recently, there have been allegations of corruption and inaction on water theft, the Darling River has run dry, and two key Basin states have threatened to quit the Plan in response to a highly divisive water recovery proposal. It’s an appalling disaster.

I’ve previously warned that the KM standard would likely face the same bleak future unless urgent changes were made to the process to facilitate much better participation, but nothing has been done in this regard as yet.

As with the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, the draft KM standard development process took a centralised technocratic approach. This is confirmed in a blog post by Ron Young, who participated in the process. He states that:

ISO standards are developed by groups of experts from all over the world, that are part of larger groups called technical committees. These experts negotiate all aspects of the standard, including its scope, key definitions and content.

However, as Harding, Hendriks, and Faruqi advise for environmental decision-making, “participation processes … must be effective and appropriate, with higher levels of participation for issues that are more complex or controversial.” The context for the KM standard is complex because the standard needs to be able to reflect the varied needs, requirements, and realities of a very diverse range of people and situations. A narrow group of technical experts can’t possibly reflect all of this complexity, so the widest range of people needs to be involved in the process. And, as David Griffiths’ blog post and the subsequent criticism from others clearly shows, the KM standard is certainly controversial.

This is why professional expertise is just one of the four sources of evidence in evidence-based practice, and one of the other three sources is stakeholder values and concerns. And, as Bal, Bijker, and Hendriks have found in their research10, it is straightforward to integrate both expert advice and public participation without compromising a process.

The bad: Land clearing controls in Queensland

If you think the Murray-Darling Basin Plan controversy is the exception rather than the norm, here’s another example, this time a mistake that I made.

When I first became involved in environmental management work, a series of positive experiences with community collaboration led me to become a very strong advocate for, and practitioner of, open, inclusive, participatory processes. However, in 2002 it was revealed that the Australian state of Queensland where I was working had one of the world’s highest land clearing rates, with devastating impacts on the natural environment, and that the clearing rates were accelerating. In response, conservation groups had initiated a campaign pushing for the introduction of strict controls on land clearing. Although I would not have previously supported such measures, I felt that the land clearing was an ecological crisis that demanded urgent action.

At the time, I was the coordinator of the Toowoomba & Region Environment Council (TREC), which covered much of inland southern Queensland where a large proportion of the clearing was occurring. So with the support of the TREC committee I decided to join the conservation group campaign, and played an active role in helping to bring about the introduction of the strict land clearing controls. The then Queensland Labor Party government introduced the controls, and by January 2007 a ban on most clearing was in place.

However, while farmers received compensation for having land clearing on their land restricted, their perspectives hadn’t been adequately considered and addressed in the development of the land clearing controls. As a result, opposition against the controls progressively grew, and a 2012 change of Queensland government from the Labor Party to the rural-oriented Liberal National Party saw legislation passed in 2013 that greatly weakened the controls.

Since then, land clearing rates have again skyrocketed, with Queensland back in the headlines for again having one of the world’s worst land clearing rates. The political orientation of the Queensland Government has since changed again, from the Liberal National Party to the Labor Party. The Labor Party government has since attempted to reintroduce strong land clearing controls, but was defeated in parliament.

The Labor Party government will shortly make another attempt to reintroduce the strong controls, but even if they succeed, the controls will only last until government changes to the Liberal National Party again. The only effective long-term solution is for both the Labor Party and Liberal National Party to work together with farmers to identity their concerns and develop measures that can satisfy both the needs of the environment and the needs of farmers.

The Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills Project is an example of how this can be done.

The good: fortunately a larger number of examples

The Queensland land clearing campaign outcomes taught me the lesson that I should never again take approaches that are low on Arnstein’s ladder. As well as the example of the Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills Project, I’ve successfully used open, inclusive, participatory approaches in a number of other notable programs and projects, both before and after the land clearing campaign.

These include:

- Hawkesbury-Nepean River Recovery Program. The Hawkesbury-Nepean catchment has a similar range of issues to the Murray-Darling Basin, but the Hawkesbury-Nepean River Recovery Program, a major initiative, established a successful partnership with stakeholders and won two major awards.

- Gatton Shire Biodiversity Strategy. The Strategy advanced innovative win-win solutions to benefit both biodiversity and the landholders and community of Gatton Shire.

- Crow’s Nest Shire Project Green Nest. Project Green Nest was acclaimed for its innovative strategies and the way in which it engaged the community, receiving a Commendation Award in the ‘Environment – Natural Resource Management: Partnerships for Biodiversity Conservation’ category in the 2002 National Awards for Local Government, and the Landcare Australia Local Government Award in the 2003 Queensland Landcare Awards.

All of these initiatives have left a lasting legacy, with stakeholders and the community having been involved to an extent that gave them long-term ownership over the outcomes.

Resources to assist with implementing open, inclusive, participatory processes

I recommend the following resources, which includes environmental resources that I consider to have wider application:

Through implementing the guidance in resources such as these, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) should move towards making its standards development processes open, inclusive, and participatory. As Holzmer writes in a recent blog post titled “The Collapse of Expertise and Rise of Collaborative Sensemaking”, this change is necessary, but likely to be challenging:

If organizations are going to thrive in these turbulent times, they must surrender many longstanding assumptions about expertise and quickly start leveraging the power of collaborative knowledge. But for many organizations, this won’t be easy as most continue to believe in the kind of power-driven, top-down knowledge management strategies common to the machine age.

However, this challenge must be met if standards like ISO 30401 are to gain the necessary support to leave a lasting legacy, as opposed to triggering a backlash that results in a disaster where very little, if any, real progress is achieved.

Header image: Men burn copies of the Murray-Darling draft plan in the NSW town of Griffith as anger mounts over the proposed cuts. Source: Picture by Nathan Edwards reproduced in J Kelly, ‘Murray-Darling Guide Fails to Sufficiently Consider Human Cost, Says Simon Crean‘, The Australian, 15 October 2010.

References:

- Arnstein, S. (1969). A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35, July, 216-24. ↩

- Connell, D. (2007). Water politics in the Murray-Darling Basin, Federation Press, Annandale. ↩

- Connell, D. (2007). Water politics in the Murray-Darling Basin, Federation Press, Annandale. ↩

- Connell, D. & Grafton, R. (2011). Basin Futures, Water reform in the Murray-Darling Basin. ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra, p. xx. ↩

- Harding, R., Hendriks, C. & Faruqi, M. (2009). Environmental Decision-Making: Exploring complexity and context, The Federation Press, Sydney. ↩

- Daniell, K. (2011). ‘Enhancing Collaborative Management in the Basin’, in Connell, D. & Grafton, R. (eds), Basin Futures, Water reform in the Murray-Darling Basin, ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra. ↩

- Recklies, D. (2001). What Makes a Good Change Agent? ↩

- Harding, R., Hendriks, C. & Faruqi, M. (2009). Environmental Decision-Making: Exploring complexity and context, The Federation Press, Sydney. ↩

- Weir, J. (2009). Murray River Country, An ecological dialogue with traditional owners. Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra. ↩

- Bal, R., Bijker, W. E., & Hendriks, R. (2004). Democratisation of scientific advice. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 329(7478), 1339. ↩

Thank you Bruce for what is clearly a lot of research and a well thought through opinion with solid examples to make the points you offer. Developing a standard is a start and the outcome for any effort is always driven by balance in the process that gets one there.

I am glad that we are moving forward with this standard and perhaps a “retrospect” (learning after a project or phase of a project) on this process would be useful in making future changes in the standards development process. I would even facilitate it!

Many thanks Bill for your comment. A retrospect could be valuable if ISO was able to take the learning on board, but sadly I think that they’re some way away from this at present.

I’ve written a further article on risks and opportunities in the implementation of the standard, which can be found at http://realkm.com/2018/04/06/implementing-km-standard-iso-30401-risks-and-opportunities/ I’m still very hopeful that we can achieve strong consensus support for the standard, and that it will help us to achieve good outcomes.

Best regards, Bruce.