How systems thinking enhances systems leadership

By Catherine Hobbs and Gerald Midgley. Originally published on the Integration and Implementation Insights blog.

Systems leadership involves organisations, including governments, collaborating to address complex issues and achieve necessary systemic transformations. So, if this is the case, how can systems leadership be helped by systems thinking?

Systems leadership is concerned with facilitating innovation by bringing together a network of organisations. These then collaborate between themselves and with other stakeholders to deliver some kind of service, influence a policy outcome or develop a product that couldn’t have been achieved by any one of the organisations working alone.

Recognising that a network of organisations can achieve something that emerges from their interactions involves a certain amount of implicit systems thinking. After all, the classic definition of a ‘system’ is an identifiable collection of two or more parts that has properties, or achieves outcomes, that can only be attributed to all of the parts interacting, not any one of the parts in isolation. These properties or outcomes may be intended (eg., a service, policy or product), unintended (eg., contributing to climate change), or both.

However, systems thinking, when pursued explicitly, involves much more than just recognising that a network of collaborating organisations is a system. It helps leaders review a wide range of opportunities for change by encouraging them to question the existing system – the boundaries of it, different perspectives on it, the relationships within it (and between it and its wider environment) and how the parts cohere into a system with particular emergent properties, achievements or impacts. Any or all of these forms of questioning could be relevant to addressing a complex issue and achieving a transformation.

Through systems thinking, leaders can generate deeper insights, guard against unintended consequences and co-ordinate action more effectively. Various systems thinking approaches exist. They can help guide (but should not dictate) processes of deliberation to improve complex problematic situations and develop more desirable futures.

Although each individual systems thinking approach has its own strengths and weaknesses, the true power of systems thinking comes from exploring the unique context at hand and designing a bespoke programme that draws on the best of many approaches. Principles and methods may be borrowed from one or more of the available approaches and creatively combined. Some of these are discussed below.

How to question assumptions

Decision-making is inevitably based on underlying assumptions about the boundary of the issue at hand, and therefore what purposes should be pursued and what values are relevant. Systems thinking can be used to surface these assumptions and consider alternatives. A number of approaches address this, including:

- Boundary Critique, or who and what should count?

By asking who and what should count early in a project, conflict and marginalisation (of both people and issues) can be identified and addressed. Understanding power relationships helps people decide which subsequent systems approaches are going to be most appropriate for policy or service design.

- Critical Systems Heuristics, which offers twelve boundary questions.

Questions such as: ‘who or what should benefit from the service, and how?’ and ‘what should count as expertise?’ help guide reflection on what the system currently is, and what it ought to be. They support people in thinking about motivation, decision-making power, sources of knowledge, and legitimation. The full set of questions can be found in a blog post by Gerald Midgley on Critical Back-Casting. The questions can be phrased in plain English, and can therefore be answered by ‘ordinary’ citizens as well as policy makers. They are particularly useful in multi-agency settings when there is a need to rethink governance.

How to explore wider contexts

Although it can seem overwhelming to explore wider contexts, there are established approaches that help with mapping the bigger picture and thinking about strategic responses:

- The Strategic Choice Approach for joined up decision making and handling uncertainty.

There are four phases of strategic choice:

- shape people’s understandings of the multi-dimensional problem;

- design several packages of possible policy responses;

- compare these packages; and

- choose between them.

This helps people think about uncertainties and contingencies. It also offers a tool to visualise multiple interacting areas of policy or practice, the options available, and how compatible they are with one another. Thus, policy or service packages can be assembled that address a range of economic, social and environmental challenges.

- The Viable System Model for assessing the responsiveness of an organisation or multi-organisational network to a changing world.

An organisation has an environment, comprised of all the changing economic, social and ecological needs, demands, opportunities and threats that the organisation might have to respond to. The Viable System Model looks at how an organisation responds to its environment in terms of operations (eg., service provision), coordination, management, intelligence about the future, and strategic oversight. The model can be used at multiple scales, so, where appropriate, relationships between local, regional, national and international systems can be visualised. It can be used to diagnose problems in existing organisations and networks, or to design new ones. Although the visual representation of the model can look complex at first, it is widely applicable and can yield powerful new insights.

How to engage people

Systems thinkers need to welcome a variety of stakeholder and citizen viewpoints, and account for them in designing or refreshing policies, services or products. Common approaches include:

- Soft Systems Methodology, offering visual techniques for exploring different stakeholder perspectives.

This involves four main activities:

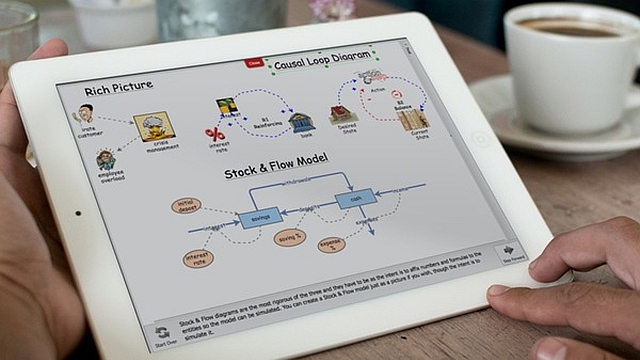

- ‘rich picture’ building, to get a visual ‘map’ of people’s perceptions of a complex problem;

- identifying possible transformations that could be pursued from different stakeholder perspectives, and visualising the actions that would be needed;

- reflecting on the options and asking what kind of transformational approach is likely to best address the problem situation; and

- finding accommodations between stakeholders to agree the most desirable and feasible way forward.

Soft Systems Methodology helps stakeholders learn collaboratively about complex situations and generate better mutual understanding of their different viewpoints on desirable and feasible change.

- Community Operational Research for citizen-engaged transformations.

Community Operational Research is about working participatively with local communities. It draws on several systems thinking approaches, including those discussed above. The focus is on meaningful community engagement in setting agendas for transformation and acting on those agendas. This work resists the top-down design and implementation of policy in favour of co-design and co-production with multiple stakeholders, communities and citizens.

Implications for systems leadership

All of the above are design-led approaches. They can aid us in thinking and acting more systemically, and they generate ‘on the ground’ insights by cultivating collective intelligence. Most of the approaches can be used in workshops, either bringing stakeholders together, or working with separate groups when power relationships make that more appropriate. Since the onset of COVID-19, many such workshops have been moved online.

If informed by these kinds of systems thinking approaches, the systems leadership practice of the future could be more exploratory, design-led, participative, facilitative, and adaptive – addressing complex, multi-faceted ecological, social, cultural, economic and personal priorities through the deliberate adoption of a process of shared endeavour. It could also help leaders better tackle the single-organisation or single-department ‘silo’ mentality that so often threatens to undermine systems leadership.

Questions for readers

What has your experience been in using systems leadership and systems thinking to address complex problems in government or other organisations? Do you have additional methods, tips or experiences to share? Do you think that useful distinctions can be made between the terminology of systems leadership and systemic leadership?

To find out more:

This blog post is adapted from the following resource, written for and published by a branch of the UK Government:

Hobbs, C. and Midgley, G. (2020). How systems thinking enhances systems leadership. National Leadership Centre, London. (Online): https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/926868/NL-thinkpiece-Systems-Leadership-HOBBS-MIDGLEY.pdf (PDF 340KB). This also provides references for all of the approaches described.

In addition, the format of this National Leadership Centre think-piece was based upon three of the five operational principles around ‘what matters?’ drawn from Catherine Hobbs’ Adaptive Learning Pathway for Systemic Leadership. For a fuller account of the Adaptive Learning Pathway and summarised descriptions of more approaches (eg., strategic assumption surfacing and testing, metaphor, Cynefin, causal loop mapping, interactive planning, lean, and vanguard), see Catherine Hobb’s (2019) book: Systemic Leadership for Local Governance. (Online): https://www.springer.com/gb/book/9783030082796?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIxfrNgcmR7wIVDSIYCh0-yQKuEAQYAyABEgIvUPD_BwE; and, her blog post Adaptive social learning for systemic leadership.

Biographies:

|

Catherine Hobbs PhD is an independent researcher located in North Cumbria, as well as being a Visiting Fellow at Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. She is a social scientist with experience of working in academia and local government, with a focus on developing multi-agency strategies in transport and health. She is interested in developing better links between the practice of local governance and scholarly expertise in order to increase capacity to address issues of complexity through knowledge synthesis. She is also interested in the potential of applying and developing a variety of systems thinking approaches (in the tradition of critical systems thinking), with the innovation and design movements in public policy. |

|

Gerald Midgley PhD is Professor of Systems Thinking in, and Co-Director of, the Centre for Systems Studies in the Faculty of Business, Law and Politics at the University of Hull, UK. He also holds Adjunct Professorships at Linnaeus University, Sweden; the University of Queensland, Australia; the University of Canterbury, New Zealand; Mälardalen University, Sweden; and Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. He publishes on systems thinking, operational research and stakeholder engagement, and has been involved in a wide variety of public sector, community development, third sector, evaluation, technology foresight and resource management projects. |

Article source: How systems thinking enhances systems leadership. Republished by permission.

Header image source: Diego Dotta on Open Clipart, Public Domain.