Active knowledge exchange with users and partners in open innovation: the case study of Xiaomi

In my recent KM Asia 2019 conference presentation, I use Chinese electronics maker Xiaomi as a very positive example of how the automotive, aircraft, and other technology-focused industries can actively exchange knowledge with their users and partners as part of a transformed knowledge management (KM) system.

As I discussed in my presentation, it’s vital that these industries embrace this transformation because of the extremely serious issues that are arising at the complex interface between technology and people, combined with the inability of traditional linear KM and enterprise process management approaches to be able to even identify, let alone address, these issues.

Chinese electronics company Xiaomi manufactures and supports a range of consumer electronics, notably high-end smartphones and a range of smart home products. The smart home products are manufactured by other companies in partnership with Xiaomi, and accessed and controlled through a Xiaomi smartphone application.

Xiaomi has existed for less than ten years, being founded in April 2010 in Beijing, China. In that short time it has risen to be rated among one of the world’s top 50 innovative enterprises. In August 2010, the company launched its first product, the smartphone operating system MIUI, which broke the monopoly of iOS and Android in this arena.

Not only was Xiaomi able to position itself for mobile Internet development, but it also garnered 500,000 loyal followers, laying a foundation for R&D of mobile phone products. Xiaomi is currently the world’s fourth largest manufacturer of smartphones, and also the market leader in India, which is the world’s second largest smartphone market.

Xiaomi’s approach is introduced in the video above, and a newly published paper1 in the journal Sustainability sets out to describe just what it is that makes this approach so effective.

Open innovation

Pivotal to Xiaomi’s success is the way in which the company actively exchanges knowledge with users and partners in an open innovation system.

Before exploring the specifics of Xiaomi’s approach, it’s helpful to have a basic understanding of the open innovation paradigm2.

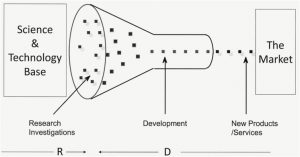

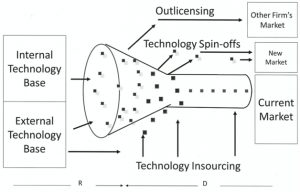

Open innovation3 assumes that as companies look to advance their innovations, they can and should use not just internal ideas, but also external ideas, and not just internal paths to market, but also external ones. Key aspects of difference between closed and open innovation systems are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

In a closed innovation system, research projects are launched from the science and technology base of the company. They progress through the development process, and some projects are stopped while others are selected for further work. A few successful projects are chosen to go through to the market.

By contrast, in the open innovation model, ideas and projects can enter or exit at various points and in various ways. Projects can be launched from either internal or external technology sources, and new technology can enter into the process at various stages. In addition, projects can make their way to market in many ways as well, such as through out-licensing or via a spin-off venture company, in addition to going through the company’s own marketing and sales channels.

Xiaomi’s open innovation system

Three kinds of products constitute the basis of Xiaomi’s open innovation system: the Xiaomi smartphone series, the MIUI smartphone operating system, and the smart home products which are manufactured by other companies in partnership with Xiaomi. Xiaomi draws on both internal and external ideas in the development of its smartphones and the MIUI, and the smart home products make their way to market through the partner companies rather than Xiaomi itself. This reflects the open innovation model shown in Figure 2.

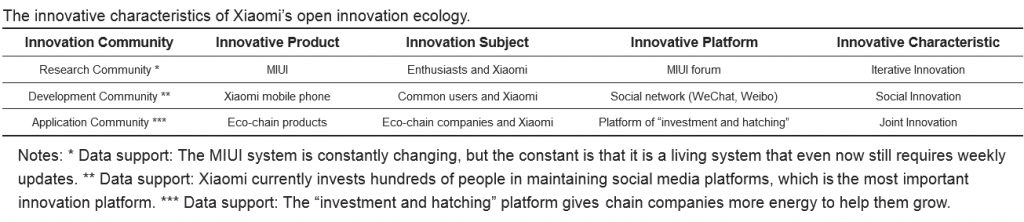

This open innovation system of core enterprises can be divided into three innovation communities: research, development, and application. The MIUI is the core on which the diverse functions of Xiaomi’s smartphones rely. The “Mi home” app on the smartphone controls 85% of the smart home products, and the ease of use of MIUI directly determines the user’s experience of the smart home products. Therefore, the MIUI is the research foundation of the innovation system. As the carrier of MIUI, the Xiaomi smartphone is also the main entrance into the smart home product chain, which forms a continuous link in Xiaomi’s innovation. This means that the Xiaomi smartphone is the result of the implementation of the innovation system. The smart home product chain further expands the scope of Xiaomi’s innovation and it is the basis for the application of the innovation system.

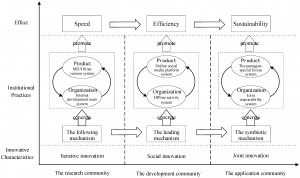

Although the three innovation communities are closely linked, each has unique characteristics. As shown in Figure 3, the study authors have determined that the research community has the innovative characteristics of iterative innovation, the development community shows the innovative characteristics of social innovation, and the application community has the innovative characteristics of joint innovation.

Iterative innovation refers to the innovative way that the core enterprise improves its products repeatedly according to user suggestions in order to better meet users’ needs. Social innovation means that core enterprises maintain good communication with users through online social media and offline activities, actively solicit users’ innovative ideas on products, and carry out targeted improvement through interactive communication. Joint innovation means that core enterprises jointly develop products through cooperation with partners based on complementary advantages and mutual benefits.

The authors also propose three new institutional mechanisms – following, leading, and symbiotic – that a core enterprise uses to effectively coordinate with users and partners participating in innovation within an open innovation system. Figure 4 shows the institutional practices that result from these mechanisms, and the effect of this.

The following mechanism guarantees iterative innovation, which primarily manifests in the core enterprise regularly updating its products, integrating innovative suggestions put forward by users in new versions of these products as quickly as possible. The leading mechanism guarantees social innovation, which is a set of institutions in which core enterprises actively prompt users to participate in innovation. Its key feature is that core enterprises determine the parameters of users’ participation in product innovation, whether improvement suggestions are adopted, and what form, scale, and types of user organizations will participate in innovation activities. A symbiotic mechanism guarantees joint innovation, which is an institutional philosophy that ensures resource sharing, information sharing, and risk sharing between the core enterprise and its partners in the processes of joint research and development.

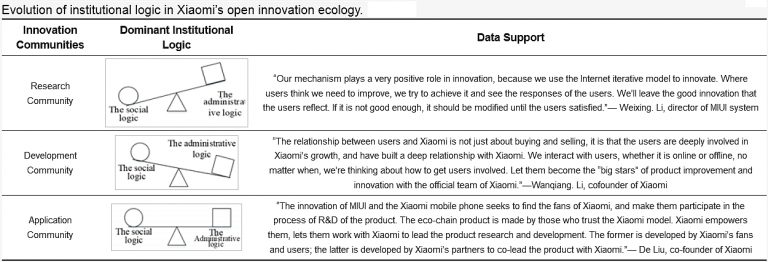

The study has identified administrative logic and social logic as two kinds of institutional logic that core enterprises follow in establishing an open innovation system on the Internet, and the choice between the two varies depending on the context of innovation. When acting in accordance with administrative logic, the core enterprise guides innovation through imposing its authority and formulating rules and regulations. When innovating through the logic of social forces, the core enterprise acts to involve external users and partners.

The authors further conclude that the fundamental requirement for the successful construction of an open innovation system is that the core enterprise accurately grasps the changing rules of multi-institutional logic. As shown in Figure 5, the dominant institutional logic that iterative innovation should follow is social logic, the dominant institutional logic that social innovation should follow is administrative logic, and joint innovation should achieve a balance between the two in research and development.

Active knowledge exchange in real time

As shown in Figures 3 and 4 and discussed in the video above, Xiaomi’s open innovation system facilitates active knowledge exchange in real time with users and partners. This means that not only can Xiaomi provide useful information directly to users and partners, but that it can very quickly identify problems and issues of concern and then immediately act to address them.

Article source: The article “Construction of Open Innovation Ecology on the Internet: A Case Study of Xiaomi (China) Using Institutional Logic” is published under a Creative Commons Attribution license.

References and notes:

- Ortiz, J., Ren, H., Li, K., and Zhang, A. (2019). Construction of Open Innovation Ecology on the Internet: A Case Study of Xiaomi (China) Using Institutional Logic. Sustainability 11(11): 3225. ↩

- For a more detailed introduction to open innovation, and how it relates to knowledge management, please see the slides from my “Transforming mindsets – leading the way with innovation” masterclass at the Knowledge Management Singapore 2018 (KMSG18) conference. ↩

- Chesbrough, H. (2012). Open innovation: Where we’ve been and where we’re going. Research-Technology Management, 55(4), 20-27. ↩

Also published on Medium.