Taking responsibility for complexity (section 3): Practical guidance for dealing with complexity

This article is section 3 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems.

In the face of the challenges complex problems pose, people could be forgiven for becoming cynical about chances of being able to tackle issues or achieve economic or social goals. Complexity could be an excuse to dodge the responsibility for failing to achieve goals, as it seems unsurprising that many policies fail to address the problems they are designed to combat and that large ambitions are abandoned to avoid creating further unforeseen problems. In particular, it might seem that ‘knowledge’ is less useful to the policy process than was initially supposed, as the ‘rational’ model of policy-making, which is centred around intentionally guiding institutions towards achieving common goals, begins to look like not just an unrealistic description of the policy process but also in fact an irrelevant ideal.

However, it would be wrong to take such a sceptical stance. The central contention of this paper is that the main problem is not intractable problems, or poor application of the right tools, but rather use of the wrong tools for the job1. And, while the traditional ‘toolkit’ for policy implementation is not sufficient to address complex problems, the complexity sciences are beginning to give us alternative theories for change, greater understandings of underlying processes and, crucially, better approaches for tackling them. It is vital that actors charged with implementing policies and programmes in the face of complexity take responsibility for choosing an appropriate approach; there are a number of insights into how to address complex problems in a strategic and directed manner.

The rest of this section is devoted to outlining how this can be done. It outlines principles and priorities as to where and when policies and programmes need to be shaped, and then a variety of tools on how to manage implementation. The last section discussed limitations in traditional rational approaches to intervention – owing to limited knowledge of different scales, limited knowledge of the future and limited understanding in the face of conflicting perspectives. However, rather than seeing knowledge as something unattainable, or not useful, when tackling complex issues, it becomes one of the most crucial resources for effective design and implementation: the ways in which policy draws on available knowledge becomes one of the central determinants of its success. The difference is that policy-makers must be mindful of constraints and opportunities as to where, when and how knowledge and decision-making can best be linked.

Before continuing, it is important to present some qualifications, caveats and ‘health warnings’, to guard against a misinterpretation of this guide or its contents. First, complexity requires a shift in perceptions as to what are ‘scientific’ or credible tools and approaches to implementation. Many of the priorities complexity highlights are not new; part of the value of complexity is that it helps us draw together a common narrative and framework on understanding that has been building up in the social sciences for decades, highlighting links and similarities that may promote further innovation and tool development. Complexity is an area of growing scientific and practical importance, based on rigorous empirical studies as well as theoretical development. It is already bringing a variety of strong lessons to longstanding fields such as macroeconomics, and is beginning to prove that certain assumptions embodied in traditional approaches to policy implementation and management are not applicable universally. By adding further weight to certain calls, for example for a wider view of ‘knowledge’ for policy, or for a focus on ‘process’ as a scientific approach that is potentially equal to that of managing for results, it may help to ensure that important stakeholders keep a balanced view of what constitutes effective and responsible intervention. It may also help bring into the mainstream things that were not considered such, making lessons from implementation and ‘rules of thumb’ more legitimate. This may be particularly important in times of pressure on budgets.

Second, clearly, the priorities and tools presented are not magic bullets. Just as with the ‘traditional approaches,’ they have a domain of appropriate application, and need to be applied well and with sensitivity. They cannot hope to solve every implementation challenge, and some of the propositions represent a ‘work in progress,’ in the sense that they have not all been tested extensively. Also while the toolkit offers a variety of important principles to bear in mind and areas to consider, it is not yet clear which implementation arrangements are most suitable for specific circumstances. The material needs to be picked up by innovative decision-makers worldwide and tested and improved thoughtfully.

Third, implementation is likely to require a mixture of these tools and more traditional approaches. Shaping policy will always be a matter or degrees, and a negotiation between bottom-up and top-down structures, between planned and emergent responses and between technical and participatory guidance. The following represents an attempt to redress the balance and provide a much-needed toolkit for half of that equation.

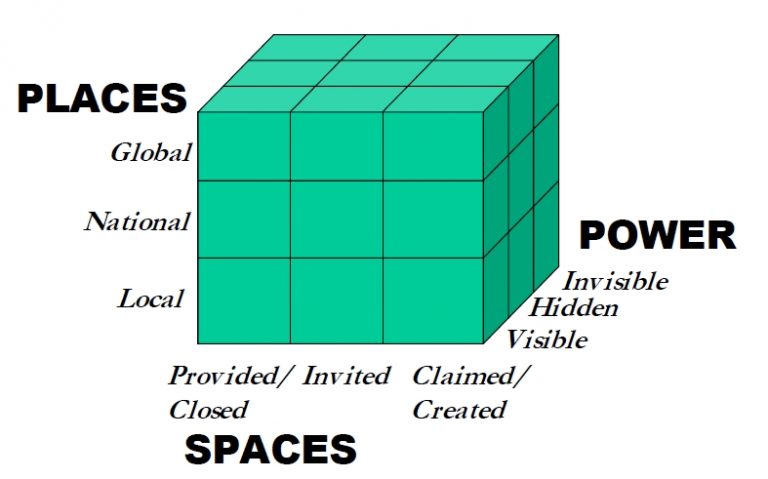

It is also likely that different types of complexity (according to the three dimensions set out in the previous section) may require a greater emphasis on different sections of the guidance presented here. For example, a highly distributed programme that focuses on relatively well-known outputs, such as vaccinations, may require a focus on the ‘where’ components more than the ‘when’ components. A relatively centralised programme operating in the face of high uncertainty may best focus on ‘when.’ However, the approaches do have some features in common, as they are building on similar principles and understandings (programming in the face of a lack of knowledge). As such, they are likely to complement each other. Rather than operating according to some kind of ‘policy cycle’ in complex problems, it could be that decision-makers consider a ‘cube’ of interfaces between knowledge and policy. These interfaces need to be cared for and linked up if possible – with one dimension being where (macro, meso, micro), one being when (before, during, after) and one being type (research-based and technical knowledge, practical knowledge such as evaluations, citizen knowledge and participation, etc.) (see Figure 1).

Next part (section 3.1): Where? Facilitating decentralised action and self-organisation.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity.

Article source: Jones, H. (2011). Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems. Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Working Paper 330. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/6485.pdf). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

References and notes:

- Even the highly critical evaluation of RBM at the UN assumes that it is a case of poor implementation rather than the wrong tool for the job. OIOS (2008). ‘Review of Results-based Management at the UN.’ Washington, DC: OIOS. ↩