Ignorance: Vocabulary and taxonomy

By Michael Smithson. Originally published on the Integration and Implementation Insights blog.

How can we better understand ignorance? In the 1980s I proposed the view that ignorance is not simply the absence of knowledge, but is socially constructed and comes in different kinds (Smithson, 1989). Here I present a brief overview of that work, along with some key subsequent developments.

Defining ignorance

Let’s begin with a workable definition of ignorance and then work from there to a taxonomy of types of ignorance. Our definition will have to deal both with simple lack of knowledge but also incorrect ideas. It will also have to deal with the fact that if one is attributing ignorance to someone, the ignoramus may be a different person or oneself. I proposed the following definition:

“A is ignorant from B’s viewpoint if A fails to agree with or show awareness of ideas which B defines as actually or potentially valid.”

This definition covers both lack of knowledge and wrong ideas. It also handles the attribution issue. A and B may be different people or they may be the same. And it leaves open the question of whether B thinks A should know something, or should not.

A taxonomy of ignorance

Now let’s turn to vocabulary. There are numerous terms we use in natural language for unknowns. Several proposals have been put forward for taxonomies of unknowns since the one I proposed in 1989, but mine is the focus of this piece.

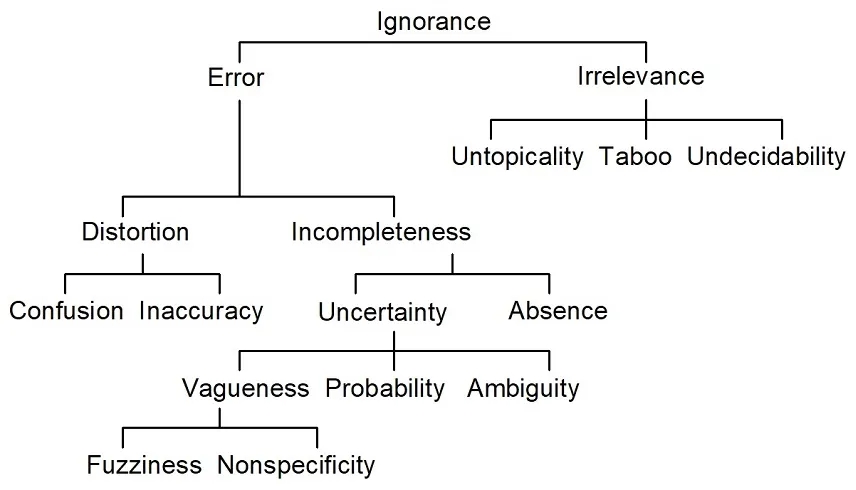

In my taxonomy, I divided the terms for unknowns into two groups:

- Error, which includes both lacking knowledge and possessing incorrect beliefs. This is the passive-voice side of ignorance, in the sense that it is a property or characteristic.

- Irrelevance, which includes all of the terms that refer to ignoring things. This is the active-voice side of ignorance, and refers to avoiding things we believe that we don’t need or want to know or that we shouldn’t know.

Under Error we have Distortion, which further subdivides into Confusion and Inaccuracy:

- Confusion is mistaking something for something else. If I try to write on paper with my tablet’s stylus, then I have confused my stylus with a pen.

- Inaccuracy amounts to mis-estimating something. I believe I have $50 in my wallet, but it turns out that I have only $20, so my estimate of the amount of money I’m carrying is inaccurate.

Under Error we also have Incompleteness, which further subdivides into Uncertainty and Absence:

- Absence is exactly what it seems: Missing information.

- Uncertainty, on the other hand, has three varieties:

Probability, Ambiguity, and Vagueness.

- Probability is uncertainty about whether something is true or whether an event will happen. A juror may think that the defendant probably is guilty, but still not be sure. I may think that it probably won’t rain tomorrow, but I’m not certain.

- Vagueness and Ambiguity are related terms that oftentimes are used interchangeably. But I prefer to keep them separate.

- Ambiguity refers to distinct possible states. So, if my friend says “this food is hot” and doesn’t say anything more than that, he could mean high temperature, or that it’s spicy, or even that it’s stolen or trending.

- Vagueness, on the other hand, refers to an interval on some sort of quantitative dimension. If my friend says he spent 30 to 40 minutes preparing a meal, he is being vague about how long that took.

Returning now to Irrelevance, we have three categories:

- Untopicality refers to things we feel we don’t need or want to know. For example, most of us, most of the time, don’t need to know the distance from the Earth to the sun.

- Taboo refers to matters that are forbidden to us. Classified military information is an example where the taboo is enforced by a powerful authority. Taboos also can be enforced via cultural and social norms, such as privacy.

- Undecidability denotes matters that, in principle, cannot be determined to be true or false. The classical liar’s paradox (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liar_paradox) is an example.

Amendments to the taxonomy

There have been several worthwhile suggestions for amendments to my taxonomy or replacements for it. Chief among my additions has been uncertainty that arises from conflicting information, ie., “conflictive uncertainty”. I and other researchers have found that people often regard conflictive uncertainty as worse than other kinds of unknowns, especially when it takes the form of disagreements among experts.

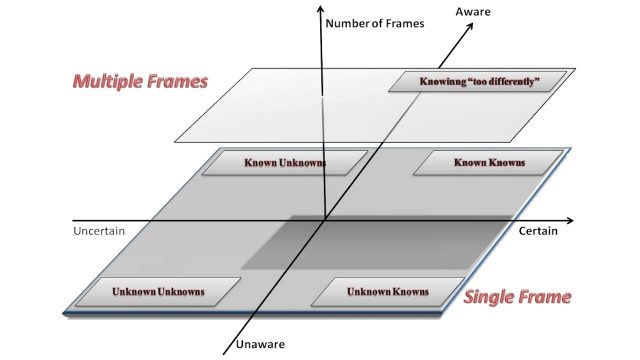

The sociologist Matthias Gross (2007) integrated some of my concepts and those from other scholars of ignorance into his “house of the unknown”. Like me, he uses “ignorance” as a cover term for not knowing, but he also assumes that this is conscious ignorance: the unknowns that we’re aware of.

“Nonknowledge” is ignorance that is sufficiently specified that, at least in principle, we could eradicate it or overcome it. For instance, if I have a question but I also know how to find out about it, then in principle I can answer it.

“Negative knowledge”, on the other hand, is Karin Knorr-Cetina’s (1999) term for knowledge about what we cannot know. For instance, I can never know what my father would have thought about my choice of career because he died when I was only 11 years old.

Thus, ignorance can become either knowledge, or nonknowledge or negative knowledge, which is a way of distinguishing between reducible and irreducible ignorance.

Matthias Gross places another term, “nescience”, outside the house of the unknown. This term is similar to my concept of meta-ignorance or Ann Kerwin’s (1993) unknown unknowns. Once we become aware of our nescience, it can become ignorance or even go straight to nonknowledge.

Nonknowledge, or reducible ignorance, sometimes can therefore be converted into new knowledge or at least an extension of older knowledge. But new knowledge also can generate new problems or questions, ie., more ignorance. Neuroscientist Stuart Firestein (2012) likes to say that the main business of scientific research is improving our ignorance.

Conclusion

So now we have some concepts and terms for talking about various kinds of unknowns. We also have a working definition of ignorance that takes into account the fact that we can’t refer to it without taking a point of view. All these terms and concepts are culturally embedded, and often differ across domains and disciplines.

How are terms such as “vagueness”, “probability”, or “risk” used in your own area? And how do those usages compare with their counterparts in, say, law, economics, or engineering?

References:

Cetina, K. K. (1999). Epistemic cultures: How the sciences make knowledge. Harvard University Press.

Firestein, S. (2012). Ignorance: How it drives science. Oxford University Press.

Gross, M. (2007). The unknown in process: Dynamic connections of ignorance, non-knowledge and related concepts. Current Sociology, 55, 5: 742-759.

Kerwin, A. (1993). None too solid: Medical ignorance. Knowledge, 15, 2: 166-185.

Smithson M (1989). Ignorance and uncertainty. Emerging paradigms. Springer Verlag.

Biography:

|

Michael Smithson PhD is an Emeritus Professor in the Research School of Psychology at The Australian National University in Canberra. His primary research interests are in judgment and decision making under ignorance and uncertainty, statistical methods for the social sciences, and applications of fuzzy set theory to the social sciences. |

See also:

- What about ignorance management? (An Information Innovation @ UTS webinar which includes a presentation by Michael Smithson.)

- MOOC on Ignorance! (An edX Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) convened by Michael Smithson and Gabriele Bammer. The MOOC is based on Michael Smithson’s pioneering work on ignorance, and Gabriele Bammer looks specifically at the importance of ignorance in dealing with complex problems.)

- Judgment and decision making with unknown states and outcomes (An article by Michael Smithson.)

- How can we know unknown unknowns? (An article by Michael Smithson.)

- Case study: How polarized debates can be the result of rational deliberation, and how they can be resolved (An article referencing comments by Michael Smithson.)

Article source: Ignorance: Vocabulary and taxonomy.

Header image source: Belle-Noir Magazine, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.