Language, knowledge, and intercultural communication

Recently I have been delving a little into the world of international auxiliary languages, also called IALs or “interlangs”. These are constructed languages designed to facilitate intercultural communication – most famously Esperanto – but there are a range of others with small but passionate communities.

For the purposes of this article, I am going to focus on three specific auxiliary languages:

- Esperanto

- Interlingua

- toki ma

The goals of those participating in interlang communities varies from the passionate advocacy of their language as a single worldwide language, to a hobby that is simply undertaken for fun.

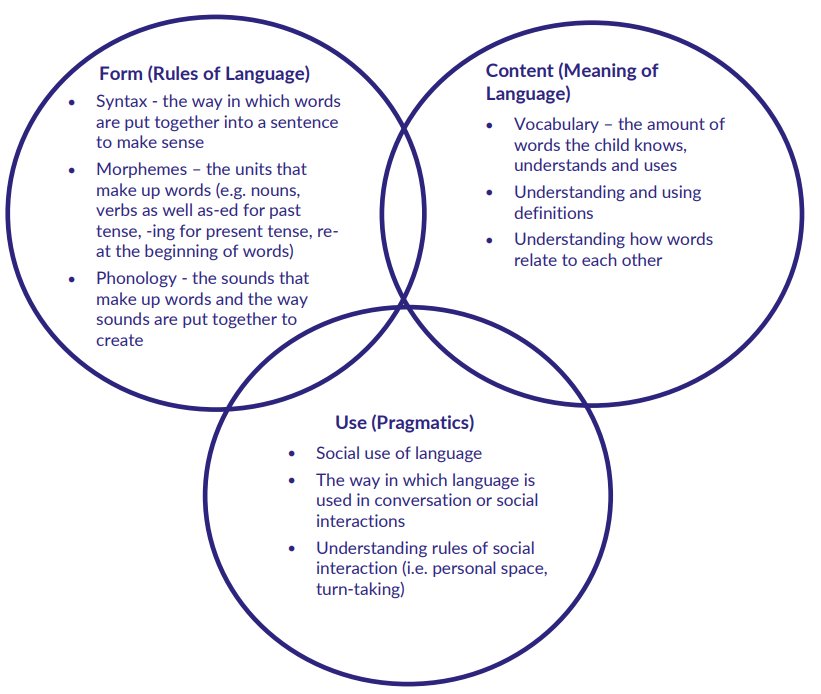

As a knowledge manager, I find interlangs fascinating because of what they expose about our assumptions around knowledge and how we share it. While there is no universal agreement on the components of language, the Bloom and Lahey model1 provides a useful starting point:

Historically, the form barriers in language learning have been the hardest to overcome, with basic differences in phonology (sounds), syntax (grammar) and writing system often making mutual understanding all but impossible.

However as tools such as Google Translate continue to improve in providing rapid translation between languages, these foundational barriers drop away. At this point in time, while the accurate conversion of syntax from one language to another in a naturalistic way remains a significant challenge, it is content and use which have become most important when considering barriers in the use of language for knowledge exchange.

So what can interlangs teach us about knowledge and how it is shared? What becomes clear is that when we seek knowledge exchange through language, three factors are paramount:

- language expression

- language precision

- language knowledge.

Language expression is the ability to physically write or speak a language. Most people of European ancestry are comfortable in speaking languages that use variants of the Latin alphabet, even those which include accents or diacritics with minimal training. However when switching to languages using other writing systems (e.g. the Cyrillic alphabet, Chinese, or Japanese), it is impossible to avoid learning the fundamentals of written communication first.

Similarly, when learning to speak a new language it may be necessary to learn new sounds (or start distinguishing between sounds that are treated the same in your language), or to learn tonal or pitch pronunciation techniques where these impact on semantic content. For example in Japanese, your pitch accent when pronouncing “ippai” determines whether you are asking for “one” or “a lot” of something!

With some exceptions, interlangs tend to be non-tonal and use the Latin alphabet. No doubt this is partly due to the bias of Western audiences to adopt language structures that somewhat mimic their own, but it is also reflective of the typical approach of interlangs to simplify their method of language expression as much as possible.

For example, Esperanto and toki ma both strictly enforce a one letter = one sound rule, while Interlingua and toki ma both use no diacritics or accents in their writing system. Taking this idea further, toki ma deliberately selects a very small set of sounds which are widely used in just about all of the world’s languages, and uses the ordinary IPA (international phonetic alphabet) characters to write them.

Language precision refers to the ability of a language to express knowledge concepts in detail. This is largely but not exclusively tied to the size of a language’s vocabulary. Unlike natural languages which develop and evolve vocabulary as and when needed, interlangs must either invent words from scratch, import them from other languages, or a combination of the two. It is common for them to also have regular rules on how to transform nouns into verbs, verbs into adjectives, adjectives into adverbs, and so on.

In this regard, Esperanto and Interlingua both borrow an extensive vocabulary but in different ways. Esperanto borrows minimal numbers of internationally recognisable word, and uses those to derive others (18 000 words). On the other hand, Interlingua allows the import of any word that can be found in multiple of its so-called “source languages” of English, French, Italian, and Spanish/Portuguese (27 000 words).

In contrast to the other interlangs, toki ma deliberately uses a minimalist language vocabulary (120 words), derived from as wide a range of source languages as possible including Arabic, Finnish, Chinese, and English.

We can see the impacts of the choices of language expression and precision in the communication of complex or abstract relationships. Toki Pona vocabulary is easy to learn, but speaking with precision is difficult and often requires a larger number of carefully selected compound words, for example:

- English: I enjoy sharing knowledge with your group

- Esperanto: Mi ĝuas kunhavigi scion kun via grupo

- Interlingua: Io ata excambiar de cognoscentia a te gruppo

- toki ma: mi li pana e sona en mi li lanpan e sona ki kulupu nan si wa mi li pasan

Of course, similar questions around language accessibility exist in natural languages as well. Public relations campaigns need to consider their audience to ensure they are communicating at a suitable level of language competence, while jargon supports precision in communication at the cost of understandability outside of a small in-group community,

Finally, language knowledge refers to a population’s experience and capability in using the language itself. This is significantly tied to how much of the language’s vocabulary they know, but also to their level of understanding of grammar, ability to rapidly construct and understand sentences, and how to apply social cues and turn-taking in language (sometimes called the “pragmatics” of a language).

Language knowledge is normally taught to a native population over many years through full immersion in the use of that language at school, work, and in a wide range of social situations. So unsurprisingly, it is also the aspect that interlangs struggle with the most.

While most interlangs have strategies to reduce the learning curve of their vocabulary and grammar, either through simplicity or extensive borrowings from other languages, the lack of critical mass in broad adoption hampers acquisition of full fluency and the development of social norms.

An excellent article2 by Paul Bartlett discusses the factors that would need to be addressed to achieve broader success of an interlang. Among other things he concludes that informal or formal institutions are essential to provide contact with other users of the language, find publications and articles to learn how to apply the language, and to participate in real-life use of the language in practical context.

(As an aside, I note that analogous benefits from institutions are available to all knowledge communities. Knowledge management continues to suffer in awareness and uptake due to a lack of institutional support.)

A common criticism of interlangs is that they often originate from and focus on language structures of the Global North. While there is no doubt some truth to this, there is an argument that moving to a language which is natively spoken by neither speaker — even if strongly influenced by a source language – can still be beneficial.

Barlett recounts an anecdote of a native French speaker who found he could communicate better in English with Germans than with other native English speakers. Bartlett’s conclusion is that “a language which [is] neither speaker’s native tongue [can be] a better medium of communication than the same tongue used when it [is] native to one.”

This represents a potential enduring advantage of interlangs over de facto languages of intercultural exchange such as English. In this context it is interesting to note that China has a significant history of Esperanto use and still publishes official news in Esperanto today3 In a recent article about the use of Esperanto in China4 a practitioner noted that:

“If China continues to grow, there will likely be a clash between the Chinese and English languages,” he says.

“When that happens, a compromise will be necessary; that’s when Esperanto could be useful.”

While it seems likely that interlangs will remain niche for the foreseeable future, at a minimum they will remain an interesting exploration of how language and intercultural knowledge exchange works, and may still have a larger role to play in the international communities of the future.

Header image source: Created by RealKM Magazine from OpenClipart-Vectors on Pixabay (1, 2), Public Domain.

References:

- Bloom, L., & Lahey, M. (1978). Language Development and Language Disorders. New York, New York: Wiley. ↩

- Bartlett, P.O. (2016, March 4). Thoughts on IAL Success. Paul Bartlett’s Auxiliary Language Files. ↩

- Esperanto.china.org.cn. ↩

- Fang, T. (2021, June 23). Esperanto, China’s Surprisingly Prominent Linguistic Subculture is Slowly Dying Out, RADII. ↩

Very interesting article, thank you. I did an introductory Esperanto course in junior high school. and our interest was excitedly sparked when our teacher told us that it would be the global language of the future. Decades later, that obviously hasn’t happened. But as you discuss, interlinguas still have potential as cultural bridge languages. An important aspect of language use in China not discussed by Tianyu Fang in his linked article on the use of Esperanto in China reinforces this, and also suggests a possible way forward.

At the beginning of his article, Fang states that “It’s probably difficult nowadays to picture a Shanghai where Esperanto is spoken in lieu of Mandarin Chinese.” That statement isn’t actually correct because the main language spoken in Shanghai is Shanghainese, not Mandarin. Shanghainese is so dominant in Shanghai that anyone from other parts of China who wants to work in Shanghai will need to first learn Shanghainese if they want to be in any way competitive in the employment market. A number of my former students have faced and met this challenge.

But Shanghainese is just one of a vast number of local dialects across China, and a “different dialect” in China means a completely different spoken language, not just accent differences. For example, my friends’ village in southern Shanxi, which has a population of around 1,000, has its own dialect, and this dialect is unintelligible to people from even the next nearest villages, which are just a few kilometres away, and vice versa. There are thousands of villages in Shanxi Province alone, which equates to a massive number of different languages. So someone from a Shanxi village who is working in Shanghai will most likely know at least three different languages – their local dialect, Mandarin, and Shanghainese. It’s also likely that they will know English and/or another foreign language such as German.

Mandarin itself actually originated from a local dialect, from the Beijing area, and has since been adopted as the national language. So Mandarin functions as a bridging language for China’s vast language diversity, highlighting how interlinguas could do the same at an international level.

Although different scripts were originally used in the different regions of China, all of the different languages across China can generally now be used with either the simplified or traditional Chinese scripts. This is similar to how the Latin alphabet is used for the written aspect of numerous worldwide languages.

Given the way in which dominant alphabets and scripts can be adapted to different spoken languages, investigating if and how interlinguas could potentially be used with both their existing alphabets and at the same time other alphabets and scripts could be a potential way forward in encouraging their wider use as a cultural bridge.