Taking responsibility for complexity (section 3.3.4): Peer-to-peer learning

This article is part of section 3.3 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems.

Work in many areas, for example social learning and on the links between research and policy, suggests that people tend to genuinely take on board messages from research or evaluation when they trust the sources from which it comes, when they have had some kind of sustained contact with the research/evaluation process and where they feel responsible for deciding for themselves how it has relevance to their particular context and challenges. An example of this can be seen in Box 12.

Box 12: Opening the black box of governmental learning

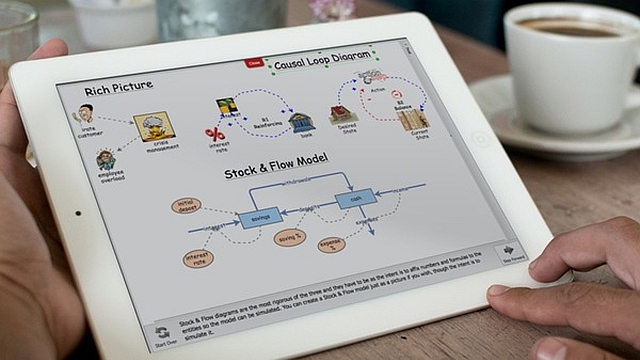

The Independent Evaluation Group of the World Bank has brought theoretical and practical perspectives together in the ‘learning spiral,’ a concept for organising learning in governments1. This provides a guide to managing learning events, helping governments learn from past practices to avoid mistakes and adopt successful practices from others. It places peer-to-peer learning at the centre of the process, so actors can learn from each other through a continuous exchange, in which knowledge is validated and updated in real time and based on the latest experiences. Ensuring a sense of social belonging among learning actors can lead to continuous exchanges and long-term knowledge exchange. The learning spiral consists of an eight-stage process:

- Before: The conceptualisation, triangulation and accommodation stages are considered the preparatory stages, where the specific challenge is defined; the knowledge framed; the selection and invitation of the participants completed; and a sense of trust between the learning actors and the event facilitators, and between the participants and the learning process, established.

- During: The internalisation, re-conceptualisation and transformation stages represent the core of the didactical procedures. Learning actors review and adapt the new knowledge according to their personal needs, then change their individual and organisational thinking and behaviour in an elaborate inter- and intra-personal procedure.

- After: In the final configuration stage, all developed knowledge is made available and accessible to everybody involved in the learning activity as well as to a wider audience. The new knowledge further serves to help frame another spin of the learning spiral.

Both formal and informal linkages between actors can provide effective channels for two-way flows of knowledge and communication between individuals and organisations, horizontally and vertically. Networks can facilitate the transfer of explicit, codified knowledge such as publications or manuals, as well as tacit knowledge that is context-specific, woven into the experiences in which it is generated. These spread in a different manner: explicit knowledge is faster to pass on and often requires externally driven incentives; tacit knowledge is (hence) more difficult to transfer, with incentives driven by positive social relationships and cultures of reciprocity2. In order to best foster social learning, there needs to be a mix of quick and slow communication processes. More efficient and faster communication means better short-term and worse long-term performance, as ‘group-think’ might easily set in. Inefficient networks are better at exploration than an efficient network, supporting a more thorough search for solutions3,4

RAPID5 research suggests that networks can have six functions in improving communication and strengthening the links between knowledge and policy: filter (helping members find their way through often unmanageable amounts of information), amplify (making little-known or little-understood ideas more widely understood), invest/provide (providing members with the resources, capacities and skills they need), convene (bringing together different people or groups of people), community building (networks promoting and sustaining the values and standards of the individuals or organisations within them) and facilitate (helping members carry out their activities more effectively and learn from their peers)6.

The informal dynamics of networks can be the most important for learning. Literature on communities of practice (CoPs) and complexity perspectives on management emphasise how ‘shadow systems’ of informal, social relationships permeate domains and are critical sources of adaptive capacity and learning. These are networks that arise in response to a common concern, problem or interest, which come together to fulfil both individual and group goals and to deepen their knowledge and expertise by interacting in an ongoing basis7. They engage in social learning, shared practice and joint exploration of ideas – collective communication that helps build shared understandings of a situation and transform underlying views, attitudes and values8. They can provide a ‘social container for linking and learning between practitioners, knowledge producers and policy processes to analyse, address and explore solutions to problems’ 9.

It seems likely that this kind of approach will bear more fruit in terms of improving decision-making in the face of complex problems than more formalised, external incentives. In addition, where a good deal of knowledge is tacit, coming from hard-earned experience and observation, accountability to an external actor who will find it hard to fully grasp the situation will be difficult. However, it will not be easy to deliver implications and recommendations from evaluation or research to potential users in the form of a few indicators or two bullet points of recommendations10. As such, many processes, such as programme design and planning or programme review and evaluation, may be undertaken most fruitfully with the involvement of networks of peers – e.g. through study tours or organised ‘peer review.’

Next part (section 3.3.5): Broadening dialogues.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity.

Article source: Jones, H. (2011). Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems. Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Working Paper 330. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/6485.pdf). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

References and notes:

- Blindenbacher, R., with Nashat, B. (2010). ‘The Black Box of Governmental Learning: The Learning Spiral – A Concept to Organise Learning in Governments.’ Washington. DC: IEG, World Bank. ↩

- Osterloh, M. and Frey, B. (2000). ‘Motivation, Knowledge Transfer and Organisational Forms.’

Organisational Science 11(5): 538-550. ↩ - Lazer, D. and Friedman, A. (2005). ‘The Parable of the Hare and the Tortoise: Small Worlds, Diversity and System Performance.’ Working Paper. Harvard, MA: JFK School of Government. ↩

- This is shown on a grand scale in Diamond’s analysis of the development and spread of the major agricultural innovations over the past 3,000 years, which shows that the topography of Europe impeded but did not fully obstruct communication, fostering heterogeneity and greater opportunities for exploration. Mainland Asia, by contrast, became effectively one functional unit. Diamond, J. (1999). Guns, Germs and Steel. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ↩

- Research and Policy in Development (ODI). ↩

- Mendizabal, E. (2006). ‘Understanding Networks: The Functions of Research Policy Networks.’ Working Paper 271. London: ODI. ↩

- Wenger, E., McDermott, R. and Snyder, W.M. (2002). Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge. Seven Principles for Cultivating Communities of Practice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press. ↩

- Muro, M. and Jeffrey, P. (2006). ‘Social Learning – A Useful concept for Participatory Decision-making Processes?’ Cranfield: School of Water Sciences, Cranfield University. ↩

- Hearn, S. and White, N. (2009). ‘Communities of Practice: Linking Knowledge, Policy and Practice.’ Background Note. London: ODI. ↩

- Cleaver, F. and Franks, T. (2008). ‘Distilling or Diluting? Negotiating the Water Research-Policy Interface.’ Water Alternatives 1(1): 157-177. ↩