Taking responsibility for complexity (section 3.2.2): Iterative impact-oriented monitoring

This article is part of section 3.2 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems.

The relaxation in ex ante requirements can be replaced by a greater focus on assessment and design throughout implementation. M&E1 efforts are crucial to the success of a policy or programme. This is not revolutionary – M&E is already recognised as a major instrument in the implementation of policies, projects and programmes worldwide. For complex problems, however, it is important to look at the effects of programmes on their surroundings – moving from monitoring and evaluation based on outputs (immediate goals such as building schools, training nurses or making credit available) to look at outcomes and impacts (what happens outside the direct work of the programme and contributes to people’s lives)2. Instead of asking whether an intervention is doing the right thing, or doing it in the right way, it is about asking whether it has the right effects.

M&E must be used to revise understandings of how progress can be achieved, not just to record progress against predefined indicators. Once it is recognised that ex ante assessment is always likely to give an incomplete picture of how to achieve change, how to work towards goals and what ‘success’ might look like, many of the tasks associated with planning must become ongoing and iterative. This way planning, monitoring and evaluation can be linked together and feed into each other.

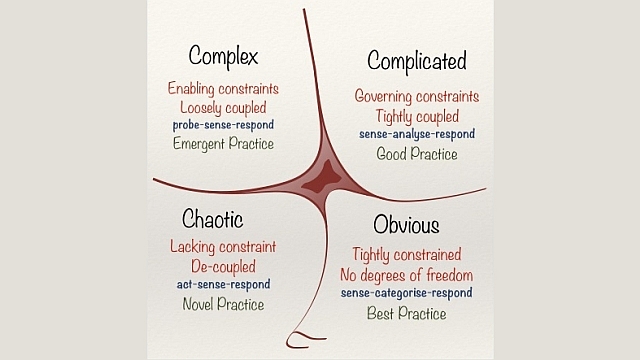

This insight is at the heart of adaptive management, which is based on the idea that knowledge about how change happens and what might make an effective policy for addressing complex problems is necessarily incomplete. It focuses on helping those formulating and implementing policy improve and develop their understanding of how the world works through ongoing cycles of evaluation, assessment and adjustment of change models and activities. It is now increasingly being applied to more social and civic issues3 (with greater attention being paid to the emerging field of ‘adaptive governance’, e.g. Folke et al.4).

Similar insights are built into outcome mapping (OM), an approach to PME5 of social change initiatives developed by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) in Canada6. OM is a set of tools and guidelines that steer project or programme teams through an iterative process to identify their desired change and to work collaboratively to bring it about. It emphasises that effective PME activities are cyclical, iterative and reflexive. Ongoing monitoring activities resemble re-planning exercises, enabling teams to revisit their various aims and objectives and adjust their understanding of how to achieve change if necessary.

Generating learning about the effects of an intervention is one matter; for it to lead to responsive action and adaptation, it must be fed into policy and practice. This means it is crucial to ensure that lessons from M&E are taken up. In the complexity sciences, this is conceived of as creating a feedback loop between implementation experience and future action which steadily brings the reality of policy/practice closer to the intended functioning and to the achievement of goals.

A variety of methods and approaches, already well-known to development practitioners, can help to ensure that emerging evidence of the effects of an intervention are reflected on and integrated into implementation. Action research, action learning methods and appreciative enquiry are just a few of these. Evaluation should be more utilisation-focused – employing the intended users and uses of evaluation as the drivers of how, when and where it is carried out and the questions it investigates. By placing users in key roles to shape and manage evaluation processes, they stand a better chance of facilitating judgement, decision-making and action7. In order to ensure they provide the requisite feedback for adaptation, evaluation and research policies, processes and studies should be judged by the utility and actual use of the information provided.

Next part (section 3.2.3): Stimulating autonomous learning.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity.

Article source: Jones, H. (2011). Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems. Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Working Paper 330. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/6485.pdf). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

References and notes:

- Monitoring & Evaluation. ↩

- Riddell, R. (2008). ‘Measuring Impact: The Global and Irish Aid Programme.’ Final report to the Irish Aid Advisory Board. ↩

- Lee, K. (2007). Compass and Gyroscope: Integrating Science and Politics for the Environment. Washington, DC: Island Press. ↩

- Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P. and Norberg, J. (2005). ‘Adaptive Governance of Socio-ecological Systems.’ Annual Review of Environment and Resources 30: 441-473. ↩

- Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation. ↩

- Earl, S., Carden, F. and Smutylo, T. (2001). Outcome Mapping: Building Learning and Reflection into Development Programs. Ottawa: IDRC. ↩

- Patton, M. (2010). Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use. New York: Guilford Publications. ↩