Managing in the face of complexity (part 3.3): B. Move from directive to collaborative management

This article is part 3.3 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper A guide to managing in the face of complexity.

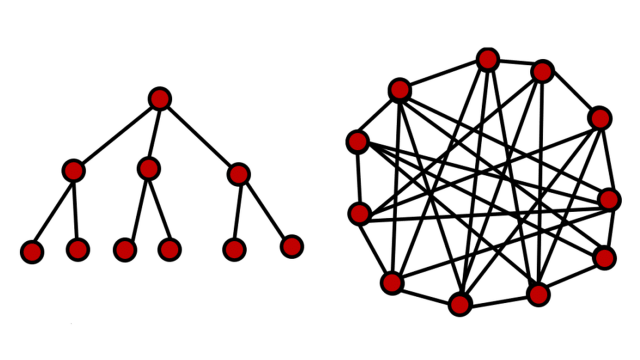

Many management models, in particular those conceived for corporate business, are based on a ‘command and control’ logic. An organisational hierarchy specifies the rules and procedures to be followed and specifies who is responsible and has the authority for decision-making. This classic model of ‘military’ style leadership is often used, but rather ineffective when faced with complexity. For example, an overly narrow set of goals and targets disincentivises the kinds of behaviour required to actually tackle complex problems1 (for more, see Box 2 on RBM). Alternative models have been developed in corporate business, public sector institutions and even the modern military to better fit complex problems.

Interventions in international development usually assume or even demand collaborative action. A programme might require assistance from civil society organisations and local communities in order to achieve its aims, or a proposed reform may need assistance and input of government Ministries which, in turn, requires the consent and collaboration of various Ministers and civil servants. Rather than working as a ‘purposive’ system, which is aligned on declared objective(s), managers face a ‘purposeful’ system, which has to pursue and accommodate multiple objectives and interests, only some of which might be known at the beginning.

Collaboration on complex issues thus takes place beyond the control of individual actors. With no hierarchy or authoritative leader to assure decision-making or resolve tensions, partners are obliged to collaboratively ‘steer’ their intervention through the troubled waters of implementation in order to reach their goals. Leadership must be relatively ‘democratic’, drawing on people’s knowledge and skills, and encouraging a group commitment to joint goals. Collaborations need strong internal communications in order to increase the level of agreement.

Limits to collaborative leadership

It should be noted that the suitability of leadership styles also depends on other factors. For instance, in times of crisis, when urgent events demand quick decisions, a democratic, consensus-building approach can be too cumbersome and an authoritarian style becomes suitable (at least temporarily). Or when development interventions are naturally organised in a hierarchical manner, command and control might work quite well, provided the partners agree on who leads.

Developing objectives

When choosing collaborative objectives, actions or resources must be negotiated and agreed. This is particularly important with collective action problems, where acting on individual incentives undermines the overall, long-term benefits to a group of actors (e.g. over-using natural resources for individual gain). Here it is essential that the stakeholders involved build a shared understanding of the problem at hand, and jointly negotiate new institutions to govern their actions and interactions2.

A number of factors are crucial in understanding and managing these kinds of initiative. Attention must be paid to:

- the perspectives of the actors involved

- interrelationships of actors and their actions

- boundary choices, which determine what is relevant and important or who benefits in which way.

Reflecting on the implications of these choices usually involves dealing with power and control issues, in particular between involved partners3.

In development interventions one will often be faced with rather messy situations or wicked problems, characterized by multiple stakeholders who have an interest in the problem and its solution, and who are engaged in multiple or unpredictable interactions. In order to reach shared understanding and agreement you will likely have to deal with rather difficult conversations, to sort out misunderstandings, contradictions or conflicts. [Part 4 of this series] … outlines several methods to deal with different aspects of these challenges (decision-making, surfacing assumptions, dis-solving problems and conflicts).

Next part (part 3.4): C. Move from centralised to decentralised management.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Taking responsibility for complexity.

Article source: Hummelbrunner, R. and Jones, H. (2013). A guide to managing in the face of complexity. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8662.pdf). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

Header image source: pxhere, Public Domain.

References:

- Ordonez, L., Schweitzer, M., Galinsky, A. and Bazerman, M. (2009). ‘Goals Gone Wild: The Systematic Side-effects of Over-prescribing Goal-setting.’ Working Paper 09-083. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School. ↩

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩

- Williams, R. and Hummelbrunner, R. (2011). Systems Concepts in Action: A practitioner’s toolkit. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ↩