Pragmatism and critical systems thinking: Back to the future of systems thinking

By Michael C. Jackson. Originally published on the Integration and Implementation Insights blog.

Would systems thinking realize its potential as a force for good in the world if it rediscovered and developed its pragmatist roots? Does the link between the past and future of systems thinking lie through critical systems thinking and practice?

In brief, I suggest that:

- Pragmatism provides an appropriate philosophy for systems thinking.

- Systems thinking has pragmatist roots.

- Critical systems thinking and practice shows how to develop those roots.

- Pragmatism can help systems thinking realize its potential and systems thinking can help pragmatism achieve what it set out to do.

What is pragmatism?

Kant was in awe of Newton’s science but believed it could supply certainty only about the physical world. In most areas of human endeavor, he argued, we have to use ‘pragmatic belief’ to guide our actions.

Charles Sanders Pierce, William James, and John Dewey borrowed the term when founding the philosophy of pragmatism. They viewed the realm in which we are forced to act on the basis of pragmatic belief as vast and hoped to make philosophy relevant again by offering guidance to help navigate it. In particular, they argued that:

- There are no universal truths. Cognition is an adaptation intimately related to our biological and historical evolution, and has developed to help us cope with the world.

- Truth should, therefore, be judged in terms of its consequences. James said – “The whole function of philosophy ought to be to find out what definite difference it will make to you and me, at definite instants of our life, if this world-formula or that world-formula be the true one”.

- The ‘multiverse’ which we inhabit allows multiple truths. James calls this ‘pluralism’, introducing the term for the first time into English-language philosophy. A multiplicity of theories should be encouraged and tested according to their consequences.

- Theories should not be seen as attempts to mirror the world but as instruments of purposeful action that can be used to change existing realities and make the world better. James said – “The truth of an idea is not a stagnant property inherent in it. Truth happens to an idea. It becomes true, is made true by events”. (The sources for this and other quotations are referenced in Jackson, 2022a.)

Systems thinking’s pragmatist roots

Warren Weaver follows a Kantian rationale in setting out the challenge posed by complexity, stating in 1948 that:

“… science has, to date, succeeded in solving a bewildering number of relatively easy problems, whereas the hard problems, and the ones which perhaps promise most for man’s (sic) future, lie ahead”.

These ‘hard’ problems – human, political, economic, social, and environmental – cause difficulties for classical scientific tools. They are, he argued, made up of too many variables to yield to simple mathematical formulae and the variables are too interrelated to yield to probability statistics. They constitute ‘a great middle region’ of ‘organized complexity’. ‘Something more is needed’, Weaver wrote, to help decision-makers tackle problems of this type. It is systems thinking that set out to provide that ‘something more’.

The three pioneers of the systems approach – Alexander Bogdanov, Ludwig von Bertalanffy, and Norbert Wiener – all adopted a pragmatist orientation in seeking to get to grips with ‘organized complexity’. For example:

- Bogdanov saw truth as “a tool for living … for the general guidance of human practice”

- von Bertalanffy championed ‘perspectivism’, arguing that all forms of knowledge can only capture certain aspects of the truth because any perspective is dependent on a “…multiplicity of factors of a biological, psychological, cultural, linguistic, etc., nature”

- Wiener gloried in taking ‘epistemological short-cuts’ on the basis of what worked.

All wanted their endeavours to secure improvement in the world:

- Bogdanov hoped his ‘tektology’ would enable people to become competent ‘world-builders’

- von Bertalanffy regarded ‘general system theory’ as entailing a rejection of the ‘robot model’ of people and as demanding “a basic reevaluation of problems of education, training, psychotherapy, and human attitudes in general”

- Wiener saw cybernetics as having major implications for the organization of society and the ‘human use of human beings’.

Critical systems thinking and practice as a development of systems thinking’s pragmatist roots

Many later systems thinkers see themselves as indebted to von Bertalanffy and/or Wiener and some acknowledge pragmatist roots (eg., C. West Churchman and Russell Ackoff). However, this is far from universal. Recently, I have been explicitly developing critical systems thinking and practice on the basis of pragmatism and seeking to show that this can enable systems thinking to realize its potential. In particular, critical systems thinking and practice argues that:

- General complexity (with interacting ontological and cognitive elements) resists universal truth. All attempts to model it are partial and, therefore, the fundamental problem posed is “epistemological, cognitive, paradigmatic” (Edgar Morin) – concerned with the ways we seek to understand and manage complexity.

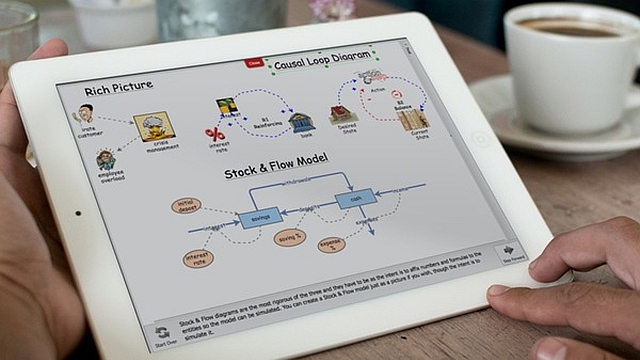

- In engaging with general complexity, systems thinking should make use of ‘systemic perspectives’ which have enabled the human species to secure coherent encounters with ‘reality’. In other words, those systemic perspectives have provided for our successful functioning in the physical and cultural worlds – specifically, the machine, organism, cultural/political, societal/environmental, and interrelationships perspectives.

- Systems thinking should embrace ‘pluralism’. It must make use of the variety of insightful systemic perspectives to view the world in different ways, and employ their associated systems methodologies to learn which of these can bring about beneficial change in a particular context.

- The purpose of critical systems thinking and practice is to bring about improvement in the world. This is not just in terms of increased efficiency and efficacy but also effectiveness, mutual understanding, resilience, antifragility, empowerment, emancipation, and sustainability.

A brighter future for both systems thinking and pragmatism

By explicitly embracing pragmatism, and taking it forward through critical systems thinking and practice, systems thinking can realize the hopes of the original pioneers and chart a bright future for itself. A shared philosophical orientation will bring greater mutual understanding between the currently disparate strands of the systems movement and more unity of purpose.

It will enable systems thinking to engage more fully with, and have greater influence on, contemporary debates in the specialist disciplines. Much of that debate, in philosophy and the social sciences, centres on pragmatist themes. It is not just systems thinking that stands to benefit from an alliance with pragmatism. As an applied transdiscipline, systems thinking can assist pragmatism in achieving what it set out to do – make philosophy relevant to everyday affairs.

What do you think? If you are a systems thinker, does this argument look like it provides a way forward? If you are not a systems thinker, what would help you better connect with our field?

To find out more:

Jackson, M. C., (2022a). Rebooting the systems approach by applying the thinking of Bogdanov and the pragmatists. Systems Research and Behavioral Science. 1-17 (Online) (DOI): https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2908

Key references to critical systems thinking and practice:

Jackson, M. C. (2019). Critical systems thinking and the management of complexity. John Wiley & Sons: New Jersey, United States of America.

Jackson, M. C. (2020). Critical systems practice 1: Explore—Starting a multimethodological intervention. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 37, 5: 839– 858. (Online) (DOI): https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/sres.2746

Jackson, M. C. (2021). Critical systems practice 2: Produce—Constructing a multimethodological intervention strategy. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 38, 5: 594– 609. (Online) (DOI): https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2809

Jackson, M. C. (2022b). Critical systems practice 3: Intervene—Flexibly executing a multimethodological intervention. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 39, 6: 1014–1023. (Online) (DOI): https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2909

Jackson, M. C. (2022c). Critical systems practice 4: Check—Evaluating and reflecting on a multimethodological intervention. Systems Research and Behavioral Science. 1–16. (Online) (DOI): https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2912

Biography:

|

Michael C. Jackson PhD OBE is an emeritus professor at the Centre for Systems Studies, University of Hull, UK. His teaching and research interests are systems thinking, organizational cybernetics, creative problem solving, critical systems thinking, management science and systems science. |

Article source: Pragmatism and critical systems thinking: Back to the future of systems thinking. Republished by permission.

Header image source: Diego Dotta on Open Clipart, Public Domain.