Five questions about psychological safety, answered

Originally published in ScienceForWork.

Key points

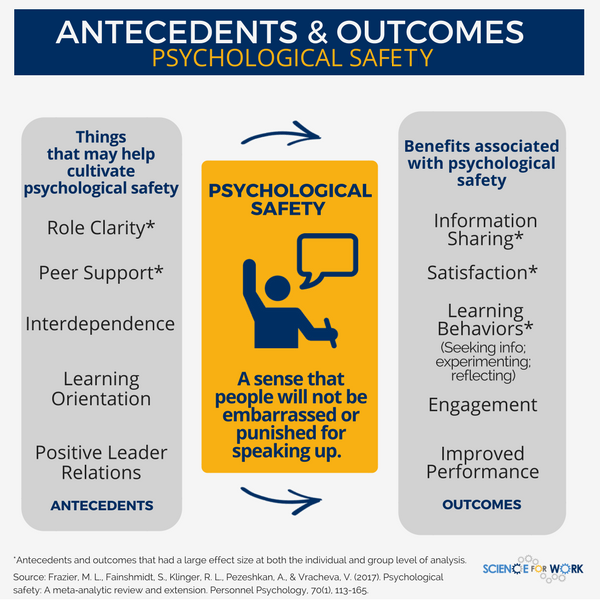

- Psychological safety exists when people feel their team is a place where they can speak up, offer ideas, and ask questions without fear of being punished or embarrassed.

- Perceptions of psychological safety are strongly related to learning behaviors, such as information sharing, asking for help and experimenting, as well as employee satisfaction.

- Things that may help to cultivate psychological safety include support from your colleagues and a clear understanding of your job responsibilities.

Psychological safety gets another look

Although the concept of psychological safety has been around since the 1960s, it recently came storming into the mainstream when research by Google on high-performing teams hit the news. While Google’s research, which focused on 180 of its teams, is illuminating, this evidence summary highlights some of the findings from a new meta-analysis on the topic by Lance Frazier and colleagues1.* They reviewed samples from 117 studies representing over 22,000 individuals and nearly 5,000 groups!

Specifically, we’ll review the answers to five important questions about psychological safety in light of these findings. Keep in mind, most of the studies included in the meta-analysis were cross-sectional, so we cannot make causal conclusions from these findings. However, we can better understand some of the factors that may contribute to psychological safety, as well as its potential outcomes.

One: What is psychological safety?

Psychological safety relates to a person’s perspective on how threatening or rewarding it is to take interpersonal risks at work. For instance, is this a place where new ideas are welcomed and built upon? Or picked apart and ridiculed? Will my colleagues embarrass or punish me for offering a different point of view, or for admitting I don’t understand something?

You might be thinking, “Is this just a fancy way of saying trust?” Although trust and psychological safety have a lot in common, they are not completely interchangeable concepts. A key difference is that psychological safety is thought to be experienced at the group level — most people on a team tend to have the same perceptions of it. While trust usually relates to interactions between two individuals or parties2,3.

Two: What benefits might arise when psychological safety exists?

Psychological safety may help to create an environment conducive to learning. Frazier and colleagues found it was strongly linked to information sharing as well as learning behaviors. Practically speaking, this might look like a team where members are more likely to discuss mistakes, share ideas, ask for and receive feedback and experiment. Sounds like a great team! Perhaps, then, it shouldn’t be surprising that psychological safety is also strongly linked to employee satisfaction!

Three: What might help to cultivate psychological safety?

Psychological safety is strongly associated with role clarity and peer support. You can probably see the logic in this. If you have a good understanding of what’s expected of you on the job and feel encouraged by your colleagues, you may feel more confident speaking up, as well as be more supportive when others do so. Additionally, the degree of interdependence on a team may play a role. For instance, if the team is one where you must count on your colleagues to get the job done, psychological safety may be more likely to develop, than on a team where most folks can complete their tasks without much help from others.

Four: Does culture make a difference?

If you work outside your home country, or in a culturally diverse team, should you think about psychological safety differently? Frazier and colleagues offer initial evidence that suggests, “Yes!” Specifically, they looked at how the role of psychological safety may differ based on “uncertainty avoidance”(UA), i.e., how much people prefer a structured and defined environment. People in high UA cultures tend to value stability, formal rules and social norms (e.g., Germany and Japan). Those in low UA cultures tend to be relatively more informal and unstructured (e.g., US and Denmark). In sum, this study indicates that psychological safety may be even more important in high UA cultures, where individuals may be culturally predisposed to avoid the type of risk-taking required to ask questions, contribute ideas and offer productive challenge to their colleagues.

Five: Can you have too much psychological safety?

Unfortunately, research to date has not yet adequately investigated if there are potential downsides to psychological safety. For instance, could it be linked with an increased likelihood for unethical behavior? Are their potential consequences for individuals, beyond what they may experience as part of their team, that should be accounted for when taking interpersonal risks? Although there is a growing body of support for the productive role of psychological safety, it’s also important to keep in mind such unanswered questions.

Takeaways for your practice

Are you interested in building a team where people ask questions, seek feedback, are willing to experiment and aim to learn from mistakes? Then make sure it feels rewarding rather than threatening for team members to do so. To cultivate psychological safety on your team, you may want to consider:

- Clarifying roles. Ensure team members understand their respective roles and responsibilities, as well as how they contribute to the team’s purpose.

- Modeling the way. Leaders can help set the tone by being curious, asking questions, and exhibiting a tolerance for mistakes.

- Considering culture. A sense of peer and organizational support may be particularly relevant in developing psychological safety in cultures that value stability and rules.

- For more ideas, you may want to check out this guide from Google’s re:Work.

Trustworthiness score

We critically evaluated the trustworthiness of the study we used to inform this Evidence Summary. We found that the design of the study was moderately appropriate to demonstrate a causal relationship, such as effect or impact. Therefore, based on this source of evidence, the claim that psychological safety has a causal effect on the outcomes considered is eighty percent (80%) trustworthy. We conclude that there’s a twenty percent (20%) chance that the results are due to alternative explanations, including random effects.

*Note: In their meta-analysis, Frazier and colleagues investigated numerous potential outcomes of psychological safety, as well as a variety of factors that may contribute to its development. For the most part, their hypothesized associations were supported and found to be statistically significant. However, the strength of many of these relationships was moderate. In this evidence summary, we chose to highlight findings that reflect strong relationships, because these are most likely to have a noticeable impact. For a full discussion of the study findings, please see Frazier (2017).

ScienceForWork

ScienceForWork is an independent, non-profit foundation of evidence-based practitioners who want to make work better. Its mission is to provide decision-makers with trustworthy and useful insights from the science of organizations and people management.

Article source: The article Five questions about psychological safety, answered is published by ScienceForWork under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Header image source: Fauxels from Pexels.

References:

- Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta‐analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113-165. ↩

- Edmondson, A. C., Kramer, R. M., & Cook, K. S. (2004). Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches, 12, 239-272. ↩

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative science quarterly, 44(2), 350-383. ↩