Knowledge hiding in organizations: Causes, impacts, and the ways forward

This article is part of a series on knowledge withholding, hiding, and hoarding.

We’ve previously reported on research which argues that, in addition to seeing knowledge as something positive to be beneficially managed, organizations also need to consider knowledge risks1. One of the identified knowledge risks is knowledge hiding. This is closely related to knowledge hoarding2, which we’ve also previously explored.

Both knowledge hoarding and knowledge hiding are the opposite of knowledge sharing. Knowledge hiding is the intentional concealment of knowledge requested by another individual, whereas knowledge hoarding is defined as the accumulation of knowledge that may or may not be shared at a later date.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the causes and impacts of knowledge hiding, a newly published paper3 from researchers at the Birla Institute of Technology and Science in India carries out a retrospective narrative review of 35 research articles on knowledge hiding published between 2008 and 2018. From the review, ways forward are recommended.

The review followed the PRISMA guidelines4, and considered only peer‐reviewed journal articles. To add rigor to the methodology, the research profiling approach was integrated into the narrative review. Research profiling generates central issues related to a topic, emphasizes techniques to study individuals from the scholarly community engaged in the particular research domain, and determines how the research domain has progressed over time.

Causes and impacts

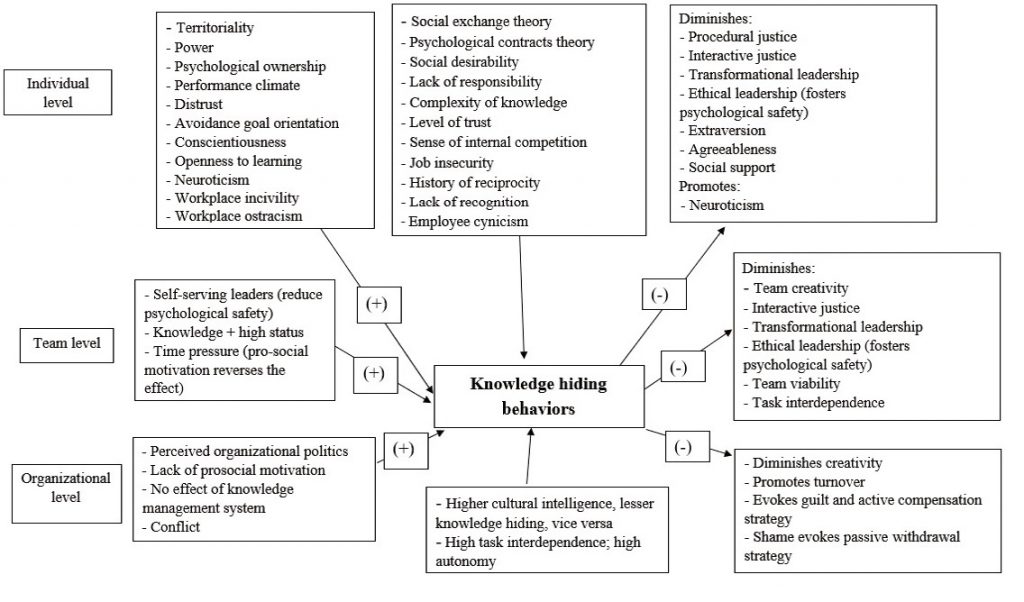

The causes (+) and impacts (-) of knowledge hiding identified in the review are summarized in Figure 1.

Implications for organizations and managers

From their findings, the authors make the following recommendations:

- Conducting training that enhances the emotional intelligence5 of employees may prevent employees from engaging in knowledge hiding practices, and can build accountability among employees.

- Promoting prosocial behaviours and organizational citizenship among employees and ingraining a sense of community will largely reduce knowledge hiding behaviours.

- Trust6 has been identified as a significant predictor of knowledge hiding, so managers should work on building trust among employees through conducting workshops that aim at building cohesion among employees.

- Constantly sharing feedback with employees (say, every fortnight or once a month) may facilitate a mastery climate among teams. A mastery climate7 promotes cooperation, learning, and skill development, which in turn promote knowledge sharing. Nurturing a mastery climate in an organization also promotes psychological safety8 and will help reduce knowledge hiding behaviors among teams.

- Perspective‐taking that involves employees getting to know each other may reduce knowledge hiding.

- Time pressure has been identified as an antecedent of knowledge hiding, so organizations seeking to promote knowledge transfer may decrease role overload, role ambiguity, work overload, and sudden deadlines. Organizations may become more productive if employees face less time pressure for completing tasks urgently.

- Knowledge hiding has emotional sentiments attached to it and is based on the emotion‐based reciprocity mechanism9. Therefore, if employees are made to emotionally attach themselves, they may become involved in moral and organization‐oriented behaviour rather than immoral and self‐oriented behaviour.

- Building ethical values among employees can reduce the adverse effects of abusive supervision among employees.

- Identifying neurotic10 employees and training them can help reduce knowledge hiding behaviours in the workplace.

- Personal competitiveness can be an antecedent of evasive knowledge hiding, and training can prove beneficial in up‐skilling and making employees competent.

- The theory of planned behaviour11 can explain whether employees plan to hide knowledge.

Article source: Dynamic Relationships Management Journal, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Header image source: Robin Higgins on Pixabay, Public Domain.

References:

- Durst, S., & Zieba, M. (2018). Mapping knowledge risks: towards a better understanding of knowledge management. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 1-13. ↩

- Bilginoğlu, E. (2019). Knowledge hoarding: A literature review. Management Science Letters, 9(1), 61-72. ↩

- Ruparel, N., & Choubisa, R. (2020). Knowledge hiding in organizations: A retrospective narrative review and the way forward. Dynamic Relationships Management Journal, 9(1), 5‐22. ↩

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339: b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj. b2535. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. ↩

- Hornung, O., & Smolnik, S. (2018, January). It’s Just Emotion Taking Me Over: Investigating the Role of Emotions in Knowledge Management Research. In Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. ↩

- Bendtsen, K. M., Uekermann, F., & Haerter, J. O. (2016). Expert Game experiment predicts emergence of trust in professional communication networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(43), 12099-12104. ↩

- Penn State University (2014). Mastery-Motivational Climate. ↩

- Delizonna, L. (2017). High-performing teams need psychological safety. Here’s how to create It. Harvard Business Review, 8, 1-5. ↩

- Schweinfurth, M. K., & Call, J. (2019). Reciprocity: Different behavioural strategies, cognitive mechanisms and psychological processes. Learning & behavior, 47(4), 284-301. ↩

- Sullivan, M. S. (2012). A study of the relationship between personality types and the acceptance of technical knowledge management systems (TKMS) (Doctoral dissertation, Capella University). ↩

- Nguyen, Tuyet-Mai, Nham, Phong Tuan, & Hoang, Viet-Ngu (2019). The theory of planned behavior and knowledge sharing: A systematic re-view and meta-analytic structural equation modelling. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 49(1), pp. 76-94. ↩

Also published on Medium.