What more could be done to address the persistence of the conceptually flawed Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)?

This article is part of an ongoing series of articles on evidence-based knowledge management.

In our previous discussions in regard to evidence-based knowledge management, we’ve provided a number of examples of organisational practices for which the evidence base is either very limited, highly conflicting, or completely non-existent. These include Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Net Promoter Score, nudge management, predictive algorithms, team building events, and restrictions on the use of social network sites in the workplace.

But arguably the most significant example that could be given would be the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), which is an ever-popular personality assessment instrument. Personality has been found to influence1 information and knowledge sharing behaviours, so a number of authors have sought to correlate the MBTI with aspects of knowledge management, for example Kumar Agarwal & Anwarul Islam2, Dueck3, Durling, Cross, & Johnson4, and Froggatt & Bibby5.

Remarkably, the MBTI continues to persist despite scholarly criticism over many years. In a newly published paper6 in Social and Personality Psychology Compass, researchers Stein & Swan take up this vexed problem:

Given its popularity, continued scrutiny is warranted. Criticisms of the MBTI from the past few decades have focused on several of its problems while having ostensibly little impact on MBTI’s popularity. Conversely, as best we can tell, MBTI is not the radar of many social and personality psychologists. Therefore, the current paper builds on past criticisms by broadly focusing on the vast difference between the MBTI theory and what social and personality psychologists would consider a valid theory. We hope this will raise awareness of the psychological idea that is shaping the public’s view of psychology perhaps more than any other and provide a teaching reference to discuss its issues.

Educating scholars and the general public in this way is a laudable aim, but will it make a significant difference, given that the MBTI remains one of psychology’s most popular ideas despite its identified flaws?

I consider that there’s more that could be done, and to support my case I’ll draw on a parallel example from the field of medicine. But before I do that, a brief introduction to the MBTI and a summary of its issues.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)

The Myers‐Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is a personality assessment developed in the 1940s by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers (image above). It is based on the psychological types theory of influential Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung. As Stein & Swan state:

According to Jung, understanding people’s behavior meant understanding what personality “type” to which they belong. Jung suggested the popular view at the time – personality was random biological variation – was incorrect. He believed observable differences in personality were orderly and consistent. Thus, Jung divided personality into innate “types.”

The MBTI assessment is now taken by millions of people worldwide each year, and is widely used in organisations including 80 percent of Fortune 500 companies and 89 of the Fortune 100 companies. It is used in both hiring decisions and as a management instrument. For example, an article in Forbes states that:

Information from personality tests help companies better understand their employees’ strengths, weaknesses and the way they perceive and process information. There are 16 Myers Briggs personality types and once that is determined, an employee usually has a better understanding of the best way to approach work, manage their time, problem solve, make decisions and deal with stress.

Issues with the MBTI

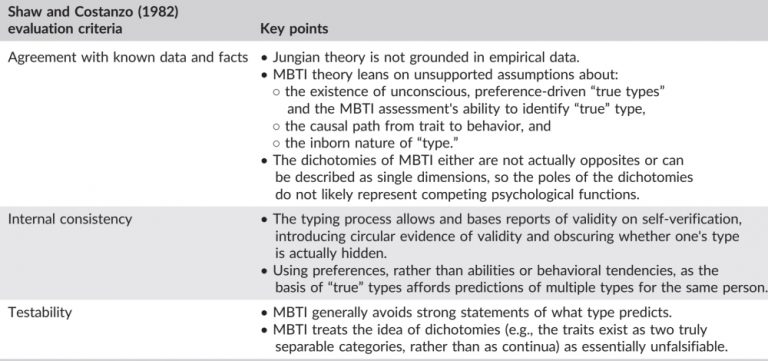

Stein & Swan have evaluated the validity of MBTI theory based on three criteria identified in the book7 Theories of Social Psychology:

(1) agreement with known data and facts (a theory’s ability to account for empirical evidence from other theories, and whether its claims can be rebuffed via pure logical argumentation),

(2) internal consistency (statements within the theory should not be contradictory with one another), and

(3) testability (ability to generate empirical predictions).

The results of their evaluation are shown in Figure 1. From these findings, they conclude that “the MBTI theory does not represent a suitable framework for understanding personality.”

In response to criticisms of the MBTI, its promoters argue that it’s descriptive rather than predictive, with the aim of helping users to gain a useful self-awareness. However, Stein & Swan state that:

This is an odd argument because decades of research on personality theories has been devoted to the … idea that predictive ability is necessary to the validity of a personality theory. Even if this is an attempt at a side step around criticism, it raises the issue of whether the process of giving people feedback on their “true self” – even inaccurate feedback – is useful.

Promoters of the MBTI also point to what they say are “[m]any studies over the years [that] have proven the validity of the MBTI instrument.” However, a systematic and critical review8 of the literature on learning styles alerts that:

The huge body of work which exists on the MBTI must be examined with the critical awareness that a considerable proportion (estimated to be between a third and a half of the published material) has been produced for conferences organised by the Center for the Application of Psychological Type or as papers for the Journal of Psychological Type, both of which are organised and edited by Myers-Briggs advocates. Pittenger asserts that ‘the research on the MBTI was designed to confirm not refute the MBTI theory’.

Stephen Bounds has exposed the serious flaws in one such piece of MBTI research in a previous RealKM Magazine article.

What more could we do?

Stein & Swan have written their paper as an educational resource, but in the closing comments of their paper they alert to a significant challenge in this regard:

if, as recent research suggests, people believe they are guided by deep, unobservable essences and that basing decisions on those deep desires is key to decision satisfaction [then] [t]he desire for this knowledge and the appeal of MBTI‐style theory is therefore an unfortunate combination, and attacking MBTI on theoretical or psychometric grounds might have little effect on what some people intuitively expect from MBTI, and/or encourage them to invent new reasons why MBTI is useful. A challenge for academics is to get others to share their valuation of the scientific process in creating knowledge about human behavior.

I contend that one way of meeting this challenge could be by providing a much starker contrast between scientifically valid theories and those that clearly aren’t. An example of this comes from the field of medicine, as shown in Figure 2.

Homeopathy is to medicine what the MBTI is to psychology – a popular idea that costs money but is very much divorced from the evidence. In February 2010, the UK House of Commons Science and Technology Committee handed down an Evidence Check report on homeopathy. The report found no credible evidence of efficacy for homeopathy, and in response was highly critical of the UK Government’s funding of homeopathy through the National Health Service (NHS) and the licensing of homeopathic products by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

In the wake of the House of Commons report, and frustrated with the persistence of homeopathy despite a lack of evidence to support it, the British Medical Association took the bold step of describing homeopathy as witchcraft. In the time since, the NHS has decided to stop funding homeopathy, with this decision upheld by the High Court. The licensing of homeopathic products by MHRA continues at this time, however the number and cost of homeopathic prescriptions has continued to greatly decline.

Could the MBTI be similarly described as witchcraft, as part of a stronger campaign to encourage a shift to evidence-based approaches in organisational and knowledge management? Perhaps this isn’t such a big step, given that research9 by Case & Phillipson has traced the alchemical and astrological origins of the MBTI:

It is in his detailed study of the works of a 16th-century Swiss alchemist, Paracelsus, that Jung makes the most direct comparison between the four astrological elements and his earlier work on the functions of consciousness and character typology … [T]he relevant passage … provides pivotal evidence for the case we are making about the relationship between the psychological types inherited by the MBTI and its alchemical/astrological origins.

From their findings, Case & Phillipson issue the following alert:

In the case of the MBTI, there is a considerable amount of academic research pursued in the name of establishing construct validity of the instruments used to generate the character typologies in order that clients can be assured of the scientific credibility of the interpretations offered. Much of this applied research in areas of career management and counselling, team building, cross-cultural studies and the like … and … conceals the astrological and alchemical origins that we have been at pains to demonstrate lie at the very heart of this typological scheme. This is where retro-organization theorizing enables us to challenge and expose the obfuscation and concealment at work. What results from the scientization of the MBTI we contend, however, is the substitution of one form of mystification – based in a premodern cosmology – by another form of mystification based on positivist scientism. [link added]

Header image source: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

References:

- Sullivan, M. S. (2012). A study of the relationship between personality types and the acceptance of technical knowledge management systems (TKMS) (Doctoral dissertation, Capella University). ↩

- Kumar Agarwal, N., & Anwarul Islam, M. (2014). Knowledge management implementation in a library: Mapping tools and technologies to phases of the KM cycle. Vine, 44(3), 322-344. ↩

- Dueck, G. (2001). Views of knowledge are human views. IBM Systems Journal, 40(4), 885-888. ↩

- Durling, D., Cross, N., & Johnson, J. (1996). Personality and learning preferences of students in design and design-related disciplines. IDATER 1996 Conference, Loughborough University. ↩

- Froggatt, T. J., & Bibby, N. J. (2007). An application of a psychometric personality type inventory to improve team development and performance. Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management Conference, Sydney, Australia. ↩

- Stein, R., & Swan, A. B. (2019). Evaluating the validity of Myers‐Briggs Type Indicator theory: A teaching tool and window into intuitive psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, e12434. ↩

- Shaw, M., & Costanzo, P. (1982). Theories of social psychology. New York: McGraw‐Hill. ↩

- Coffield, F., Moseley, D., Hall, E., & Ecclestone, K. (2004). Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review. Learning and Skills Research Centre, London. ↩

- Case, P., & Phillipson, G. (2004). Astrology, alchemy and retro-organization theory: An astro-genealogical critique of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator®. Organization, 11(4), 473-495. ↩

Also published on Medium.

In answer to your question “could the MBTI be similarly described as witchcraft”, the approach I’ve taken is to coin a phrase that seems to have the desired effect every time the topic of MBTI crops up:

Corporate Astrology

This phrase has the added bonus of injecting some levity into the conversation.

A lovely phrase – hope you don’t mind if I steal it!