Planning for the fascinating social complexity of Chinese cities, and what it can teach the west

This article is part of an ongoing series of articles on stakeholder engagement, and also part of an ongoing series of articles on cultural awareness in KM.

Our view of the world can distort our knowledge

After seeing “what it can teach the west” in the headline for this article, you may well have started reading it with raised eyebrows and a furrowed brow. After all, you’ve looked with wide-eyed wonder at all those negative stories about urban development in China, like the ones about the ghost cities. What positive messages could there possibly be for the west in this?

I too viewed the stories about ghost cities with wide-eyed wonder, but I expect that my surprise was for very different reasons.

One of the most well-known of the western media’s ghost city reports is the 60 Minutes television story, “China’s Real Estate Bubble”, which first aired on 3 March 2013 and was rebroadcast on 3 August 2014. Information from the story was also repeated by other news outlets, for example Business Insider and News Limited.

The primary location for the 60 Minutes story was Zhengdong New Area, a district of Zhengzhou, the capital city of Henan province in central China.

I watched the story in stunned amazement, having been to Zhengdong New Area in August 2009, January 2011, and May 2012. It was certainly quiet in 2009, but had very much picked up pace by January 2011, and was abuzz in May 2012, before the 60 Minutes story first went to air. Wade Shephard confirms this in his report of a visit to Zhengdong New Area at the same time as the 60 Minutes story:

The area that 60 Minutes shot in surely looked “ghost-like” on film, but when I arrived there I found an entirely different scene. I found a sparkling new financial district that was full of sparkling new cars, well-dressed pedestrians, corporate offices of major businesses, skyscrapers full of occupied offices, expensive coffee houses, laundry hanging in the windows of luxury condos, there were cars parked in nearly every available parking space, and signs of life everywhere. There was nothing desolate about the Zhengdong CBD, it appeared to be functioning as planned.

By 2015, Zhengdong New Area was thriving, with a population of over 1.4 million people, as well as being a key business, industry, and education centre and a major transport hub.

This isn’t at all surprising. Henan province has a population of more than 100 million. It had previously been considered one of the most underdeveloped provinces in China, so under the leadership of Li Keqiang, who is now Chinese Premier, a program of intensive urbanization and industrialization was initiated. The establishment of Zhengdong New Area has been a key part of this urbanization program. Only a small percentage of Henan’s 100 million people would need to move to Zhengdong New Area to populate it, and that’s exactly what’s been happening.

It’s the same with China’s other supposed ghost cities. As Wade Shepard states:

For the past few years I’ve been chasing reports of ghost cities cities around China, but I rarely ever find one that qualifies for this title. Though the international media claims that China is building cities for nobody I often find something very different upon arrival.

Why do the ghost city stories perpetuate? Perhaps it’s because people in western countries are unable to comprehend the implications of China’s massive and urbanizing population. Just Henan province alone has 100 million people, which is equivalent to nearly one-third of the entire population of the United States (325 million) and four times the population of the whole of Australia (24 million, the same as just the Chinese city of Shanghai). Or perhaps it’s a way of masking jealous fears about the future in western countries, for example in response to the rise of ghost towns in the tragically decaying world of America’s industrial heartlands. Or perhaps it’s just plain old stereotyping, with “Westerners … so convinced China is a dystopian hellscape they’ll share anything that confirms it.” An example of this are recent stories claiming that restaurants and food stores in the United States could be selling imported rat meat from China as chicken wings. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) exposed the stories as fake news, but not before they had been widely shared by people who should have known better.

However it’s caused, the perpetuation of the ghost city myth means that people in western countries don’t have an accurate knowledge of China’s cities. But it’s not just the media and the general public who circulate myths about Chinese cities, unfortunately academia is guilty of it too.

A classic example can be found in the caption to the image below, which heads the article “Our cities need to go on a resource diet”, published on The Conversation in December last year. The article itself is excellent, and very much recommended reading, but sadly the caption below the image perpetuates a widely-circulated myth in regard to one of China’s icon cities, Shenzhen.

The city of Shenzhen is located adjacent to Hong Kong in the Pearl River Delta area of south-eastern China’s Guangdong province. It was established in 1980 by then Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping as China’s first Special Economic Zone.

While it’s true to say that Shenzhen has over the past 35 years grown from a fishing town into the megacity it is today, it’s not true to say that Shenzhen was a fishing town 35 years ago. These seemingly similar expressions actually have very different meanings. As Shenzhen has grown from one small fishing village, which was located in the current Shenzhen district of Luohu, it has encompassed a large number of other villages. Rather than Shenzhen being “a fishing town 35 years ago”, it was actually 304 villages1 with a combined population of around 300,000 people2.

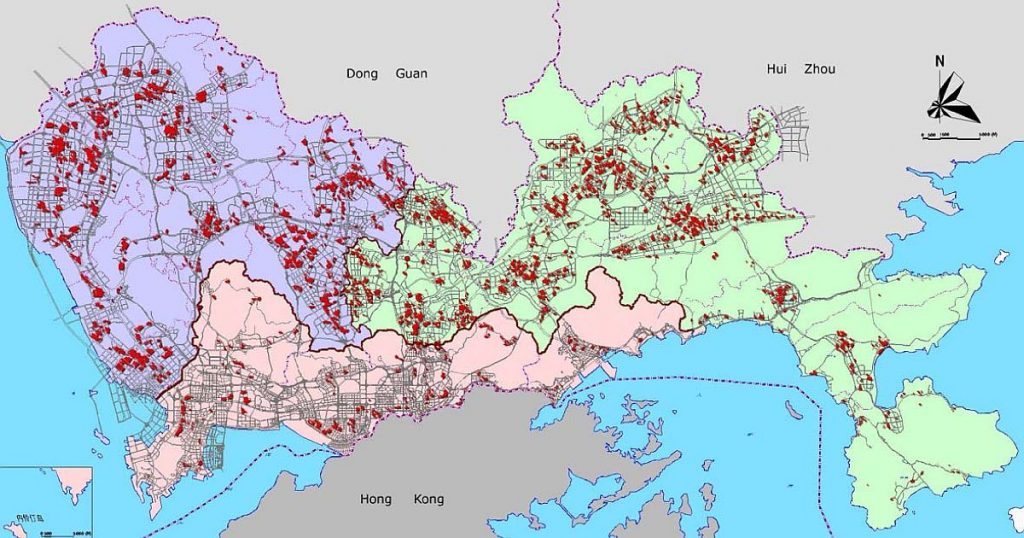

Before you consider making excuses for the caption error made by the authors of the article “Our cities need to go on a resource diet”, be aware that the article authors could and should have been aware of two doctoral dissertations investigating Shenzhen’s villages: “Villages” in Shenzhen—Persistence and Transformation of an Old Social System in an Emerging Mega City3 and Shenzhen’s Urban Villages: Surviving Three Decades of Economic Reform and Urban Expansion4. The following map comes from the first of these dissertations. Further, an awareness of China’s historically large population combined with a knowledge of historic landscape settlement patterns in China should have alerted them that it would be extremely unlikely for a landscape like that of Shenzhen to have had just one town.

The myth of Shenzhen previously being just one fishing town is itself false knowledge, which people shouldn’t be spreading. But the impact is greater than just the spread of false knowledge. The perpetuation of the myth has meant that a fascinating story about Shenzhen’s villages is being overlooked, a story which contains important knowledge of potential benefit to urban planning in western countries.

If you’re worried that “village” and “town” are being used interchangeably, the term “village” in China describes a settlement that is typically much more substantial than a village in western countries, and more like a town. For example, the following image shows Shenzhen’s Huanggang village in the 1970s, prior to the establishment of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone. It probably better fits the definition of town, as it is a substantial built-up area with a name and defined boundaries, and was politically self-governed.

Also evident in the image is the extent of landscape modification that had occurred before Shenzhen’s phase of growth into a megacity began. This further highlights the inappropriateness of circulating the myth that Shenzhen was “a fishing town 35 years ago.”

How have Shenzhen’s villages persisted?

Remarkably, rather than just being bulldozed as the megacity of Shenzhen was established and has continued to expand, many of Shenzhen’s villages continue to persist as “urban villages” scattered throughout the modern city. Anywhere in Shenzhen, people can step from wide tree-lined streets of glittering modern skyscrapers into another world: the bustling narrow alleyways of villages.

As the two doctoral dissertations discuss, not only do the urban villages persist, but so do a range of historic buildings central to village life, for example temples and ancestral halls, as well as many cultural traditions. For the two years I lived in Shenzhen, I spent many fascinating hours exploring the villages. I was guided by the first of the two doctoral dissertations, “Villages” in Shenzhen—Persistence and Transformation of an Old Social System in an Emerging Mega City, and insightful articles written by my friend James Baquet in the Shenzhen Daily, the city’s English language newspaper. The photograph at the head of this article is of a temple in Shixia village, which was one of several villages close to the apartment building where I lived for my first year in Shenzhen. As well as the temple, Shixia village also has ancestral halls, a village square with ancient trees, and a watchtower (diaolou) that had been recently restored.

Shenzhen’s villages have persisted despite the emergence of significant social complexities5, including:

- the urban villages now being home to around half of Shenzhen’s population of 12 million people, many of them “migrant workers” who have come to Shenzhen from other parts of China

- the construction of a significant number of illegal buildings that don’t comply with modern building or safety standards

- many people considering the villages to be undesirable urban slums and havens for crime.

As in western cities, Shenzhen’s villages face strong pressure from the local government to modernize, and from the development industry to redevelop. How have they been able to resist this pressure?

The doctoral dissertation Shenzhen’s Urban Villages: Surviving Three Decades of Economic Reform and Urban Expansion advises that, despite the political power of village councils having been reduced, the villages have still been able to effect a high degree of self-government through the establishment of urban village companies6:

A clear milestone was reached in 1992, when the villagers were persuaded by the city government to establish village joint-stock companies. From this point on, most of the former village chiefs became the new chairpersons of the village companies. Political administration became the monopoly of the city government.

and:

…the urban village company has essentially become a form of localized shadow government within the Chinese city. Through elections, via the urban village company, the urban villagers have in theory participated in democratic self-government within the city of Shenzhen.

As in western cities, this self-government obviously has to occur within the constraints of government policy and planning, and also in the face of developers who are making attractive offers. But through their urban village companies, the villagers are able to work with both government and developers to achieve the best possible outcomes that meet government objectives, facilitate development opportunities, and very importantly allow for the villages to maintain their sense of community and cultural traditions.

How can this self-government approach help the west?

In its abstract, the doctoral dissertation Shenzhen’s Urban Villages: Surviving Three Decades of Economic Reform and Urban Expansion states that7:

This thesis … [presents] the urban villages of Shenzhen as self-governing urban communities with flaws but [that] are overall beneficial for their residents of original villagers and rural-to-urban migrants.

Further, Juan Du, Assistant Professor in the Department of Architecture at the University of Hong Kong, advises that8:

In essence, these Villages in the City have become providers of affordable housing, close-knit social networks, and mixed-use developments … Not recognizing the historical significance of Shenzhen’s past and present would lead to a missed opportunity to learn from such a sweeping, although unplanned, urban experimentation at a massive scale. Shenzhen, examined as China’s accidental invention toward a radical hybrid urban structure could serve as a conceptual model for sustainable urban development in the Greater Pearl River Delta region and around the world.

Let’s contrast this with a recent urban planning process in Australia.

The Toowoomba Region is a local government area located around 2 hours drive west of Brisbane, the capital city of the Australian state of Queensland. It was created in 2008 through the amalgamation of eight smaller local government areas, including the Shire of Crows Nest where I worked as natural resource management officer on a one-year project in 2001-2002. The project was commended for the way in which it engaged the community.

Toowoomba Regional Council recently released the draft Highfields Cultural Precinct Master Plan for public consultation. As is the case in Shenzhen, the city of Toowoomba is a growing urban and regional centre (although at an obviously much smaller scale). Because of this, both Toowoomba Region Council and the development industry see the rural residential area of Highfields, which is located just north of Toowoomba city, as becoming a more significant urban area with a substantially higher population. Highfields was already the fastest growing location in Queensland between 2001 and 2011. The draft Highfields Cultural Precinct Master Plan was prepared in response to this anticipated future growth and an identified need for new cultural facilities.

If implemented, the plan would bring about significant change to Highfields, including the proposed resumption of up to 14 homes and negative impacts on the Charles and Motee Rogers Bushland Reserve. Because of my previous involvement with this bushland reserve, a community group that is fighting to save it has informed me about the draft plan and sought my advice.

As a result of the scope of the proposed changes and a lack of consultation with existing residents, the draft plan triggered outrage, leading to the establishment of the Hands Off Our Highfields community group. One of the elected Toowoomba Region Councillors made the following statements on social media in regard to the draft plan consultation:

Toowoomba Region Council’s actions in regard to the draft Highfields Cultural Precinct Master Plan are completely at odds with the democratic self-governance achieved in Shenzhen’s urban villages.

As well as being authoritarian rather than democratic, Toowoomba Region Council’s process with the draft Highfields Cultural Precinct Master Plan has been a serious knowledge management failure. Council has tragically wasted an opportunity to inform Highfields residents about its intent for the area, and to then work with them in a cooperative atmosphere of knowledge exchange to develop a master plan that would facilitate the best possible outcomes for everyone.

Highfields has a strong sense of community, just like in Shenzhen’s urban villages. Everyone in that Highfields community has knowledge, ideas, and perspectives that are of value. Including the widest range of knowledge, ideas, and perspectives in decision-making processes enriches those processes and leads to better outcomes.

Indeed, as I’ve previously discussed in RealKM Magazine, I have already implemented Australian projects in which residents and other stakeholders have been given a high-level of decision-making power, for example the Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills Project. This project was carried out in an area located just a short distance to the east of Highfields, and was very successful. I’ve also talked about the dangers posed by leaving people with important knowledge out of decision-making processes.

In the face of the community backlash, Toowoomba Region Council has since backed away from the controversial aspects of the draft Highfields Cultural Precinct Master Plan. However, there’s currently nothing to stop them reintroducing those aspects of the plan at some point in the future, or to prevent them from carrying out similarly flawed processes elsewhere. Or to prevent other Queensland local governments from doing the same thing.

The lessons

Governments at all levels in western countries like Australia need to look at the self-government that has been achieved in Shenzhen’s urban villages, and consider how they might be able to achieve similar. The urban village company model of Shenzhen’s villages is one way in which this can be done, and has the advantage of being a secure long-term arrangement. However, there are other approaches, for example the approach I took in the Helidon Hills.

Additionally, the general public, media, and academics in western countries need to look at how they can overcome their inaccurate views of countries like China. In doing so, they need to stop circulating false knowledge, and can bring about the situation where they open themselves up to potentially rich sources of knowledge that they may have previously ignored or overlooked. A good place to start is becoming aware of cognitive biases.

Header image: Temple building, Shixia village, Shenzhen (photograph by author). Image is licenced by CC BY 2.0.

References:

- Ma, H. (2006). “Villages” in Shenzhen—Persistence and Transformation of an Old Social System in an Emerging Mega City (Doctoral dissertation, Bauhaus University, Weimar, Germany), p. 25. Retrieved from http://e-pub.uni-weimar.de/opus4/files/771/MaHang.pdf ↩

- Da Wei David Wang. (2013). Shenzhen’s Urban Villages: Surviving Three Decades of Economic Reform and Urban Expansion (Doctoral dissertation, University of Western Australia), p. 51. Retrieved from http://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/files/3239567/Wang_Da_Wei_David_2013.pdf ↩

- Ma, H. (2006). “Villages” in Shenzhen—Persistence and Transformation of an Old Social System in an Emerging Mega City (Doctoral dissertation, Bauhaus University, Weimar, Germany). Retrieved from http://e-pub.uni-weimar.de/opus4/files/771/MaHang.pdf ↩

- Da Wei David Wang. (2013). Shenzhen’s Urban Villages: Surviving Three Decades of Economic Reform and Urban Expansion (Doctoral dissertation, University of Western Australia). Retrieved from http://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/files/3239567/Wang_Da_Wei_David_2013.pdf ↩

- Da Wei David Wang. (2013). Shenzhen’s Urban Villages: Surviving Three Decades of Economic Reform and Urban Expansion (Doctoral dissertation, University of Western Australia). Retrieved from http://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/files/3239567/Wang_Da_Wei_David_2013.pdf ↩

- Da Wei David Wang. (2013). Shenzhen’s Urban Villages: Surviving Three Decades of Economic Reform and Urban Expansion (Doctoral dissertation, University of Western Australia), pp. 62 & 100. Retrieved from http://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/files/3239567/Wang_Da_Wei_David_2013.pdf ↩

- Da Wei David Wang. (2013). Shenzhen’s Urban Villages: Surviving Three Decades of Economic Reform and Urban Expansion (Doctoral dissertation, University of Western Australia), p. i. Retrieved from http://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/files/3239567/Wang_Da_Wei_David_2013.pdf ↩

- Du, J. (2009). Urban Myth of the New Contemporary Chinese City, Journal of Architectural Education 63(2), 65-66. ↩