Just how rational is our thinking? Time for a reality check… [Thinking is hard series]

This article is part of the Thinking is hard series from Buster Benson, offering insights into the cognitive biases that distort our thinking, and exploring related topics such as debate, persuasion, and systems thinking.

We all like to think that we approach or respond to everything in a rational manner. However, the way our brains have evolved to deal with fundamental problems that humans face means that in reality we have a wide range of cognitive biases.

As defined by Wikipedia,

A cognitive bias refers to a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, whereby inferences about other people and situations may be drawn in an illogical fashion. Individuals create their own “subjective social reality” from their perception of the input. An individual’s construction of social reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behaviour in the social world. Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, or what is broadly called irrationality.

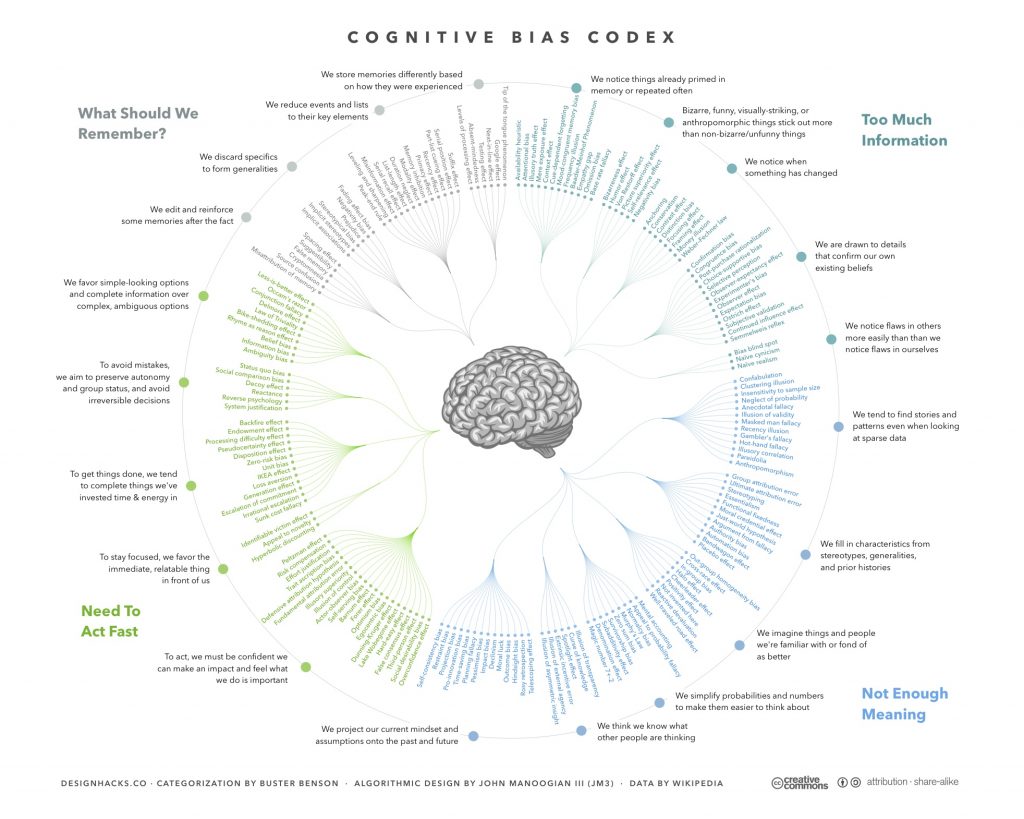

Buster Benson, a senior product manager at Slack Technologies, has taken the information contributed to the cognitive bias page on Wikipedia and turned it into a cognitive bias cheat sheet. To do this, he grouped a revised list of biases under 20 unique biased mental strategies that we use for very specific reasons. In turn, the 20 strategies are grouped under the four general mental problems that they are trying to address: information overload, lack of meaning, the need to act fast, and how to know what needs to be remembered for later:

- Information overload sucks, so we aggressively filter. Noise becomes signal.

- Lack of meaning is confusing, so we fill in the gaps. Signal becomes a story.

- Need to act fast lest we lose our chance, so we jump to conclusions. Stories become decisions.

- This isn’t getting easier, so we try to remember the important bits. Decisions inform our mental models of the world.

Our cognitive biases help us to survive in this world, but mean that we don’t see that world rationally. Further compounding the situation, our solutions to these problems also have problems:

- We don’t see everything. Some of the information we filter out is actually useful and important.

- Our search for meaning can conjure illusions. We sometimes imagine details that were filled in by our assumptions, and construct meaning and stories that aren’t really there.

- Quick decisions can be seriously flawed. Some of the quick reactions and decisions we jump to are unfair, self-serving, and counter-productive.

- Our memory reinforces errors. Some of the stuff we remember for later just makes all of the above systems more biased, and more damaging to our thought processes.

What can we do to address our cognitive biases?

Benson says that we need to learn to live with our cognitive biases, and recommends visiting his cheat sheet once in a while to remind ourselves of the four problems of the world and what our brain does to solve them.

A summary of cheat sheet is presented below. John Manoogian III has also produced the following graphical representation of the cheat sheet (click to enlarge).

Summary of cognitive biases

Problem 1: Too much information

- We notice things that are already primed in memory or repeated often.

- Bizarre/funny/visually-striking/anthropomorphic things stick out more than non-bizarre/unfunny things.

- We notice when something has changed.

- We are drawn to details that confirm our own existing beliefs.

- We notice flaws in others more easily than flaws in ourselves.

Problem 2: Not enough meaning

- We find stories and patterns even in sparse data.

- We fill in characteristics from stereotypes, generalities, and prior histories whenever there are new specific instances or gaps in information.

- We imagine things and people we’re familiar with or fond of as better than things and people we aren’t familiar with or fond of.

- We simplify probabilities and numbers to make them easier to think about.

- We think we know what others are thinking.

- We project our current mindset and assumptions onto the past and future.

Problem 3: Need to act fast

- In order to act, we need to be confident in our ability to make an impact and to feel like what we do is important.

- In order to stay focused, we favor the immediate, relatable thing in front of us over the delayed and distant.

- In order to get anything done, we’re motivated to complete things that we’ve already invested time and energy in.

- In order to avoid mistakes, we’re motivated to preserve our autonomy and status in a group, and to avoid irreversible decisions.

- We favor options that appear simple or that have more complete information over more complex, ambiguous options.

Problem 4: What should we remember?

- We edit and reinforce some memories after the fact.

- We discard specifics to form generalities.

- We reduce events and lists to their key elements.

- We store memories differently based on how they were experienced.

Also published on Medium.