Digital Amnesia: Memory, internet and modern life

Do you panic when you think you’ve lost your phone? Or do you feel sad at the thought of losing pictures and texts forever? Research has shown that you are definitely not alone – these feelings are more common than you might think. According to a recent study commissioned by global cybersecurity company Kaspersky Lab spanning more than 6 regions including UK, Germany, Spain, Italy, France and Benelux, emotional and psychological reliance on devices is a side effect of Digital Amnesia.

Digital Amnesia is a phenomenon coined as part of the Kaspersky Lab study referring to “the experience of forgetting information that you trust a digital device to store and remember for you”. It is becoming increasingly common in the age of the internet to just look something up instead of remembering it (there’s even a cheeky site parodying this called let me google that for you). When presented with a question, over half of the UK respondents (52.1%) in the study would attempt to look something up on the internet first. Once the information was used, over a third of the UK people surveyed (33.4%) would then forget it. A further 17.7% in the study did not even note down the information as they were confident that it would be able to be retrieved again. These figures were at the most extreme end and it is worth comparing the UK figures with those of other locations included in the study. Nonetheless, it does confirm that many people are “[using] the internet as an extension of their brain”.

This study shows that this reliance on the internet and devices has increased with time, noting that:

“across Europe, more than half of adult consumers could phone the house they lived in aged 10, but not their children or the office – without first looking up the number. Around a third could not remember their partner’s number… Yet up to 60% have perfect recall of their home phone numbers when aged 10 and 15 – often reflecting the needs of an age when connected devices were not the ubiquitous companions they are now, if they existed at all.”

The presence of the internet and devices then is changing how we remember, and perhaps we are conditioning ourselves to forget pieces of information because we can simply find the information when we need it. It also shows that we trust the device to remember it for us. As Rodriguez comments, the devices can “often remember more about our lives than we do”. Moreover, Dockrill posits that the upside to forgetting ‘facts’ that we can look up on the internet is that we can “optimise the recollection of things that we really think are important.”

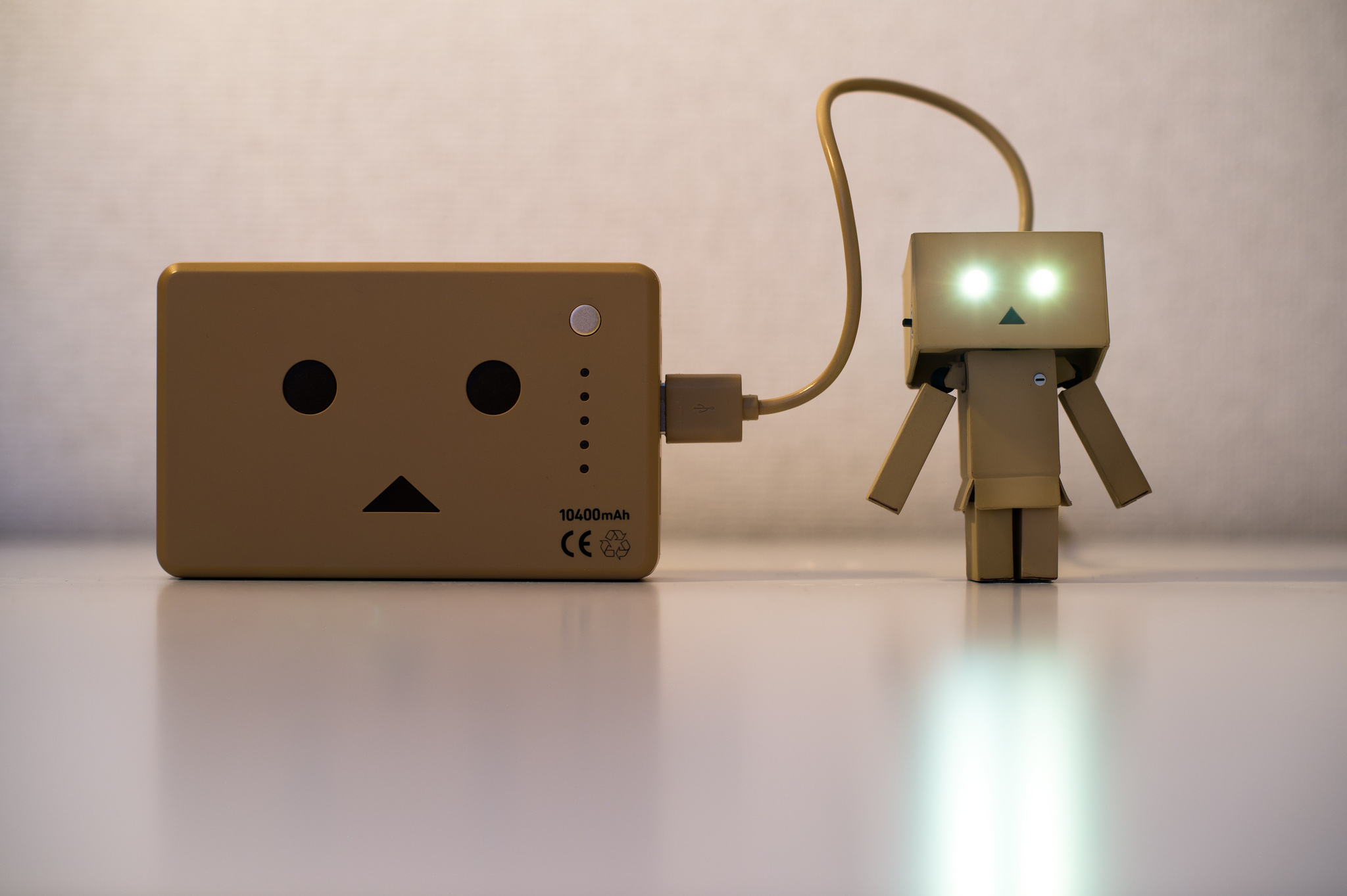

This means the loss of a device or access to data has a marked “emotional impact” according to the Kaspersky Lab study. This is because the loss of a device or access to data can evoke emotions of sadness because you might have lost photos which you took to commemorate an event. Or even losing the ability to contact someone because you cannot recall their number. The study also links the emotion of panic at the loss of a device or access to data because it is the only place or copy where the information is stored. This means that a backup or copies of information could change how we feel about loss of a device. Increased opportunities to back up files in the cloud and apps to transfer phone data such as Samsung Smart Switch continue to shape and challenge where we store our memories. Moreover, mobiles are a means to access apps, so the device itself is not as significant if the data can be accessed through other screens. This confirms that the internet is really being used as an extension of the brain.

Dr Maria Limber notes in the Kaspersky Lab that there are limitations to entrusting our memories to pictures on devices as “more often people remember the same events, the more likely they forget other relevant memories that are not captured in pictures”. It also raises the question of accuracy – in the age where photos are often filtered before being posted, are we in a sense altering memories? As this study on photo filters notes, filtered photos affected rates of engagement with the photo. Researchers suggest that “filtered photos are 21% more likely to be viewed and 45% more likely to be commented on by consumers of photographs.” This means that people are more likely to engage with photos, in this case memories, that have been altered. This may have implications for the future especially if those same images are pulled up again and displayed to friends to reference an event.

With the rise of Digital Amnesia and the delegation of remembering to digital devices, further avenues of research could include the possible effects of withholding technology unintentionally due to the effects of the digital divide or intentionally as a disciplinary measure.

Image source: Recharging Danbo Power by Takashi Hososhima is licensed by CC BY-SA 2.0.

Also published on Medium.