Knowledge exchange and creation at the grassroots

The terms knowledge sharing, knowledge transfer, knowledge exchange, knowledge translation, knowledge co-creation – to name but a few – are all describing roughly the same phenomenon. No term is necessarily better than the other. They come from different traditions but all serve their purpose.

The recent paper Knowledge, social capital, and grassroots development: insights from rural Bangladesh1 applies the influential Nahapiet and Ghoshal framework2 on social capital and knowledge creation and exchange in firms to processes of knowledge creation and exchange in a development project in Bangladesh.

In this paper, we found that trust appeared to play an even more important role in knowledge creation and exchange at the grassroots than in organizations (and probably also communities of practice). To quote from the paper: “Gift, trust and positive feelings are the hidden mechanisms of this development [project].” For me, however, the biggest eye-opener was the fact that trust is very contextual:

Linked to the exchange of gifts, trust appears to play a far more important role in [Bangladesh] than it does in the Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) framework, possibly because the project was taking place in a context with low levels of trust – where NGOs are not trusted and where women are not trusted to be able to contribute to their own, their household’s and their community’s development. Fisher has identified the link between trust and knowledge, arguing that ‘trust provides an essential catalyst enabling passive information to be transformed into usable knowledge’ (Fisher, 2013, p. 13).

This latter part of the quote gives a nice link to the contribution of trust to knowledge.

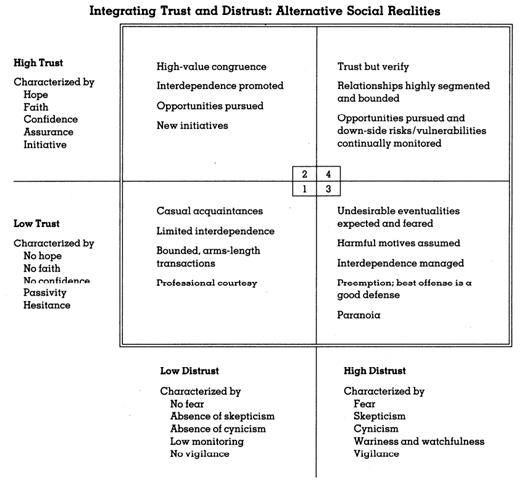

An earlier paper from the same project Trust building and entrepreneurial behaviour in a distrusting environment: a longitudinal study from Bangladesh4 by Jeroen Maas and colleagues uses a conceptual framework developed by Lewicki and colleagues (1998) that considers ‘trust’ and ‘distrust’ to be different phenomenon that co-exist. In this framework, trust represents a continuum, ranging from low trust to high trust while distrust is a continuum ranging from low distrust to high distrust as you can see in Figure 1.

What implications does this have for knowledge sharing in organisations and in CoPs? I believe that for knowledge sharing to work very well, organizations need to offer a high trust-low distrust environment, although knowledge sharing can probably also work in a high trust-high distrust environment when the incentives are clear. What implications does this have for our work in international development? When introducing development interventions, we need to recognise that people who are living in environments of high distrust, characterized by fear and wariness, find it more difficult to trust because mistrust is safer. And that if they are encouraged to trust, they will be taking enormous risks which they often can’t afford. This means that development projects which are changing modalities of trust need to be long term and also to bear the risk taken by the poor people they are trying to help. This was indeed that case in the development project in Bangladesh.

This short article was posted in response to the discussion chain ‘Understanding the role that trust plays in Knowledge transfer and our over reliance on technology’ on 23 April 2018 on the discussion list of the KM4Dev community.

Header image source: Image 1630493 by Myriams-Fotos on Pixabay is in the Public Domain.

References:

- Cummings, S., Seferiadis, A. A., Maas, J., Bunders, J. F., & Zweekhorst, M. B. (2018). Knowledge, Social Capital, and Grassroots Development: Insights from Rural Bangladesh. The Journal of Development Studies, 1-16. ↩

- Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. The Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242-266. ↩

- Fisher, R. (2013). ‘A gentleman’s handshake’: the role of social capital and trust in transforming information into usable knowledge. Journal of Rural studies, 31, 13-22. ↩

- Maas, J., Bunders, J. F., & Zweekhorst, M. B. (2014). Trust building and entrepreneurial behaviour in a distrusting environment: a longitudinal study from Bangladesh. International journal of business and globalisation, 14(1), 75-96. ↩

- Lewicki, R. J., McAllister, D. J., & Bies, R. J. (1998). Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities. Academy of management Review, 23(3), 438-458. ↩