Taking responsibility for complexity (section 3.1.6): Supporting networked governance

This article is part of section 3.1 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems.

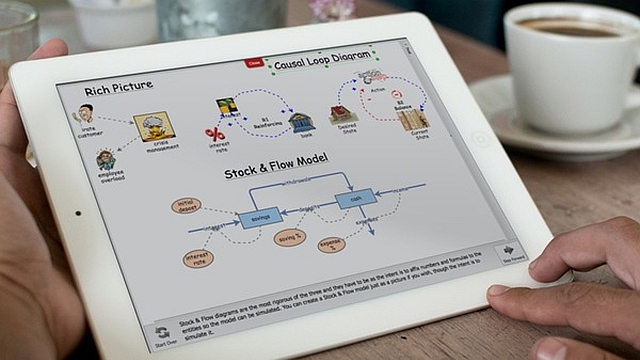

Since traditional command and control approaches are less relevant for complex problems, implementation must draw on other ways to embed accountability, as well as different ways of thinking about responsibility and mandate. What this implies is a networked approach to policy and governance. A number of experts in public sector management have hailed this as an emerging form of policy implementation1, and it has also recently been proposed as key to improving the work of international development agencies 2. Governance by network involves agencies working with a variety of institutions, engaging service providers and other organisations (including civil society organisations (CSOs), local government agencies, etc.) and collaborating with a variety of actors who have the capacity, knowledge and legitimacy to address a particular problem3. In the UK, the Institute for Government have recently argued that, since policy-making and implementation are intrinsically linked, with outcomes changing throughout implementation and central government are unable to directly control how changes happen, it must instead work towards ‘System Stewardship’, helping to oversee the ways in which policy is adapted and attempting to steer actors towards certain outcomes if appropriate4.

Given that most complex issues encountered do require the voluntary collaboration of different actors and institutions, it is crucial to build up relationships. Strong social capital and positive institutional links between the actors involved are needed, and arrangements for joint or delegated action should be negotiated. Relationships need to represent something more like agreements and fair partnerships based on shared principles, values and aims5. This means relationship management should be seen as a key activity, along with related skills and systems6. This is echoed in the literature on organisational participation and promoting collaboration within organisations, which shows that attempts to tackle problems in a decentralised manner must be supported by training in relationship skills, such as communication and conflict resolution7.

Accountability structures should focus more on holding teams, units or organisations responsible for their mission, rather than solely for delivering outcomes. Research has shown that, in facing complex tasks, accountability based on principles rather than outcomes has a positive effect on cognitive efforts put into decisions8. This could mean, for example, NGOs and other partners being funded based on, and evaluated against, their core values and mission rather than outcomes they may not be able to predict or control. Similarly, approaches to the networked organisation in the private sector emphasise the value of focusing on the functional descriptions of different teams or units, with ‘role clarity and task ambiguity,’ achieved by defining roles sharply but giving teams latitude on approach9.

Organisations becoming good ‘listeners’ and participatory processes need to be central to implementation and management: coherent and sustainable polycentric arrangements require the building of open lines of communication and linkages between different institutions and fora. One priority is for programme evaluations shaped around consultations with partners and beneficiaries. In this, there are areas of promising good practice, such as ActionAid’s Accountability, Learning and Planning System (ALPS), which is stimulating ongoing change in the agency’s planning, strategy, appraisals, annual reports and strategic reviews, bringing them more in line with principles of downward accountability. This has included revolutionary new practices, such as scrapping the requirement for formal annual reports from country offices in favour of annual participatory review and reflection processes, which engage the poor and other stakeholders in honest and open dialogue. Also, individual performance appraisal should focus on systems such as ‘360 degree appraisal.’

Building trust within organisations or teams is also important, and can be supported by a variety of policies. Focusing performance bonuses on teamwork and collaborative success is one approach10, with organisational participation shown to be promoted where compensation is built on collective achievements (e.g. profit sharing). ‘Signature’ relationship management practices have proven highly successful, ensuring that new teams and units are populated in part by people who already know and trust each other11. Informal dynamics are also important, so efforts should be made to build a sense of community, to co-locate key staff and to emphasise organisational symbols and culture. Methods should be put in place to effectively manage conflict in a consistent way, and should be an integral part of business processes such as planning and budgeting12.

Next part (section 3.1.7): Leadership and facilitation.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity.

Article source: Jones, H. (2011). Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems. Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Working Paper 330. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/6485.pdf). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

References and notes:

- One of three emerging forms of policy implementation: reinvented government built around performance-managed bureaucracies, governance by network, and governance by market. Kamarck, E. (2007). The End of Government … As We Know It: Making Public Policy Work. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner. ↩

- Barder, O. (2009). ‘Beyond Planning: Markets and Networks for Better Aid.’ Washington, DC: CGD. ↩

- Kamarck, E. (2007). The End of Government … As We Know It: Making Public Policy Work. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner. ↩

- Hallsworth, M. (2011). ‘System Stewardship: the future of policy making?’, Working Paper. London: Institute for Government. ↩

- Roche, C. (1999). Impact Assessment for Development Agencies: Learning to Value Change. Oxford: Oxfam. ↩

- Eyben, R. (ed.) (2006). Relationships for Aid. London: Earthscan. ↩

- Harvard Business Review (2009). Collaborating across Silos. Boston: MA Harvard Business Press. ↩

- Lerner, J. and Tetlock, P. (1999) ‘Accounting for the Effects of Accountability.’ Psychological Bulletin 125(2): 255-275. ↩

- Gratton, L. and Erikson, E. (2007). ‘Eight Ways to Build Collaborative Teams.’ Harvard Business Review 85(11): 101-109. ↩

- Evans, P. and Wolf, B. (2009). ‘Collaboration rules’, in Collaborating across Silos, Harvard Business Review, Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA. ↩

- Gratton, L. and Erikson, E. (2007). ‘Eight Ways to Build Collaborative Teams.’ Harvard Business Review 85(11): 101-109. ↩

- Weiss, J. and Hughes, J. (2005). ‘Want collaboration? Accept – and actively manage – conflict’, Harvard Business Review 83(3):92-101. ↩