Co-creative approaches to knowledge production and implementation series (part 6): What qualities and considerations should characterise co-creative research?

This article is part 6 of a series of articles based on a special issue of the journal Evidence & Policy.

In the second of the papers in the research section of the special issue, Nicholas and colleagues1 seek to stimulate discussion on what qualities and considerations should characterise co-creative research.

The language of co-creation in research and consulting has become popular with policy makers, researchers and consultants wanting to support evidence-based change. However, Nicholas and colleagues advise that there is little agreement about what features research must have for it to be co-creative, and therefore for it to contribute to the growing body of practice and theory in that regard.

In response, the paper offers a framework to support researchers and practitioners in discussing the boundaries and the features that are beginning to characterise the discourse that is unfolding around the concept of co-creation.

The hope of Nicholas and colleagues is that a shared discourse of co-creation in research will provide a basis for critical reflection and improved practice, and a platform for debating issues of ethics, legitimacy and quality in strongly participative projects.

Such outcomes will not only guide research design and practice, but also assist funders and those who review and evaluate research. For example, funders will have a basis to assess the aptness and implications of a decision to adopt a co-creative methodology.

Defining co-creation

As a context for their framework, Nicholas and colleagues put forward a working definition of co-creation. They alert that there is no consensus among scholars on the term ‘co-creation’, although a number of definitions and distinctions have been suggested.

Nicholas and colleagues view co-creation as an approach to research that values the expertise and perspectives of those likely to be affected by the work, and those who utilise insights from the work. They distinguish co-creation from other concepts by relating it to the quality of processes and relationships developed through a programme of work, rather than by seeing it as merely a means to an end.

This is not to say that such processes are a sufficient end to justify the research, merely that it would be part of the desired outcome. Research design and chosen methodologies will still need to demonstrate that they are well suited to achieving conventional goals such as knowledge generation, hypothesis testing, and deepening understanding.

Nicholas and colleagues also suggest that co-creation in research can be guided by concepts from service-dominant logic2. A foundation of service-dominant logic is the concept of co-creation of value, and Nicholas and colleagues see co-creative research as co-creating value. As service-dominant logic has it, ‘value is cocreated by multiple actors, always including the beneficiary’, ‘all social and economic actors are resource integrators’, and value in human exchange is to be determined by the beneficiary.

This stands in contrast to solutions to social problems that require experts to devise strategies that those experts assume will be passively accepted by service recipients. Researchers, then, would not deliver value through their work, but rather participate in the creation of value. The difference is important: ‘delivery’ assumes that the control of value lies in the hands of the researcher alone, while ‘participating in the creation of value’ indicates that the researcher is just one contributor to synergistic value creation.

Nicholas and colleagues propose that co-creative research, characteristically, recognises that knowledge creation and social change are outcomes of engagement between multiple actors holding diverse expertise and perspectives, and often exercising unequal power.

Co-creation, then, is systemic in a sense: it considers the boundaries of who is and what issues are to be included, and the values that help determine those boundaries, and it assumes complex interactions between actors and with the environment.

Critical Systems Heuristics framework

The paper therefore takes a ‘systemic’ stance in exploring co-creation. Nicholas and colleagues consider it useful and important to make explicit that decisions about how to conduct research are made within a context of value judgements about what purposes to pursue, boundary judgements about whose views and what issues are relevant, and relationships between stakeholders who may make different value and boundary judgements.

If co-creative research is, as proposed in the paper, a way of working that is intentional about decisions of inclusion, then a framework drawn from the field of critical systems thinking, that defines being systemic in the above terms, is likely to prove useful in exploring core qualities at the heart (and soul) of what is distinctive about co-creative research. Critical systems thinking has been described as including an emphasis on power relations and how they affect both what problems are addressed and how they are perceived, and can be distinguished as the use of systems thinking in the service of reflective practice.

The critical systems thinking approach adopted in the paper is an application of Critical Systems Heuristics3, a framework developed by Werner Ulrich. Critical Systems Heuristics builds on systems philosophy, American philosophical pragmatism, and European critical social theory.

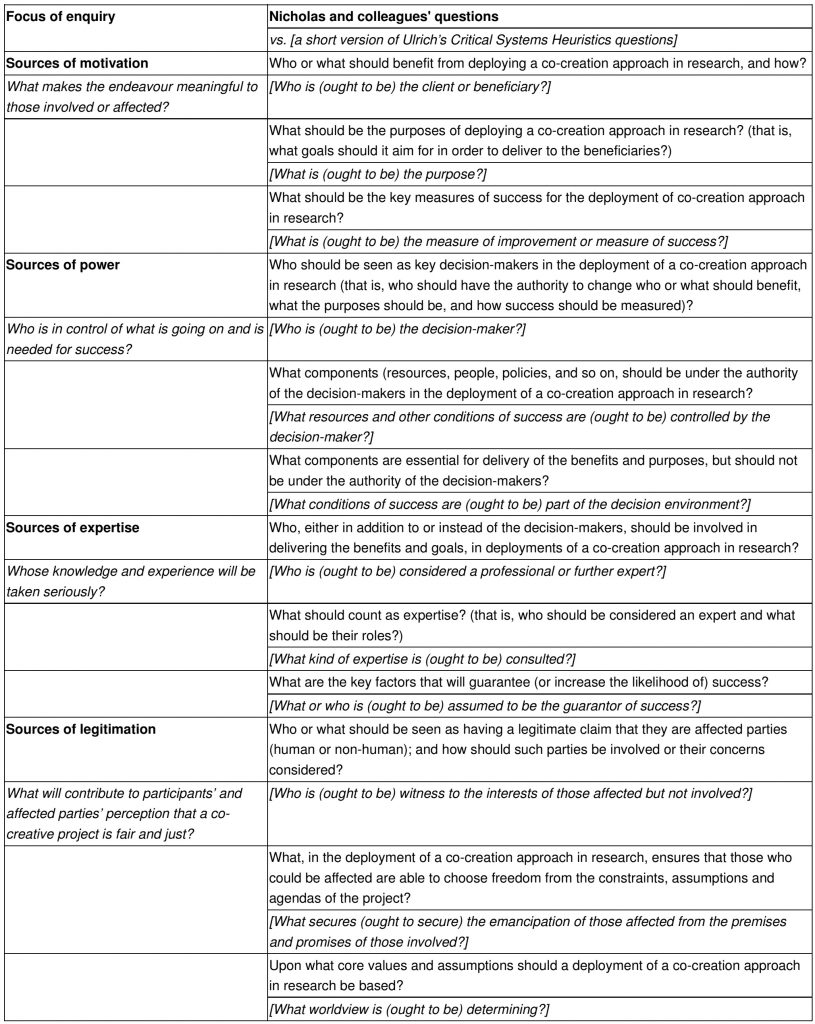

Critical Systems Heuristics offers a way to systematically reflect on practice to make explicit the boundary and value judgements implicit in it. It can be applied to truth claims, method selection, or intervention design. For the purposes of the paper, Critical Systems Heuristics provides a framework of twelve questions with which to interrogate research and social interventions. The twelve questions examine sources of motivation, power, expertise/knowledge, and legitimation. These questions can be applied to the situation as it is, and the situation as it is desired to be.

The framework can be used collaboratively with affected parties, thus addressing the Critical Systems Heuristics questions from multiple perspectives and establishing a basis for critique by parties with relatively less power than those who are directly involved in preparing or carrying out an intervention.

Critical Systems Heuristics is typically applied as a tool for reflective practice at project level (be it research or social intervention). Nicholas and colleagues are however applying it at a meta-level, to critically reflect on the framing of an emerging discourse, based on their collective experience of developing and evaluating systemic and participative methods.

When applied to a project, the questions serve as a discipline to make present the interests of those who may be affected but not involved in any meaningful way. The questions can be used by those in power to become aware of the way decisions can or do marginalise certain parties; and they can be used by the marginalised to challenge and critique the dominance of those controlling an agenda.

When applied at a meta-level, as Nicholas and colleagues do in relation to co-creative research, Critical Systems Heuristics questions surface assumptions about inclusion and roles, and can be used by those adopting the discourse to discuss desired norms for that discourse. They enhance debates about ethics, legitimacy, and quality. While they do suggest ways in which the Critical Systems Heuristics questions can guide project-level decisions, the main purpose of Nicholas and colleagues is to establish dialogue among researchers about what delimits co-creative research.

They have adapted the twelve questions to suit this task, as shown in Figure 1. The main changes to wording were to apply the enquiry specifically to the deployment of a co-creative approach to a project. The focus, then, is the framing of a project.

Detailed descriptions of each of the twelve questions in Figure 1 can be found in Nicholas and colleagues’ paper.

Nicholas and colleagues’ decision to use Ulrich’s Critical Systems Heuristics is based on their wish to demonstrate its potential usefulness for exposing the boundaries of, and assumptions flowing into, a concept like co-creation. Critical Systems Heuristics is presented in the paper as a tool to interrogate and discuss the boundaries of an emerging discourse, rather than as a definitive or required method or component of co-creative research.

They caution that it is possible that the scope and practice they have attached to the term co-creation will leave some researchers sceptical about its practical application. How can current funding mechanisms support an endeavour that claims at the outset that neither method nor participation is rigidly fixed? How can researchers and practitioners committed to co-creative practice generate the deliverables associated with merit attributions, such as peer-reviewed journal articles and generalisable knowledge? While acknowledging such concerns, Nicholas and colleagues have attempted to position co-creative practice in a way that will assist those choosing that path to argue the integrity and nature of their approach.

Inviting a reflective dialogue

Nicholas and colleagues’ offer their paper as an invitation to their colleagues in research who have adopted or are considering co-creative approaches, to enter a reflective dialogue about how co-creative choices and processes might be mutually appraised.

They look forward to robust critique of the framing of the paper, and hope that the outcome will be a self-critical discourse among researchers and practitioners about what to look for in projects that aspire to be co-creative.

Next part (part 7): Critical success factors for building trust and sharing power for co-creation in Aboriginal health research.

Article source: Adapted from the paper Towards a heart and soul for co-creative research practice: a systemic approach published in the Evidence & Policy special issue Co-creative approaches to knowledge production: what next for bridging the research to practice gap?, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Acknowledgements: This series has been made possible by the publication of the special issue as open access and under a Creative Commons license. The guest editors and paper authors are commended for their leadership in this regard.

Header image source: Adapted from an image by Michelle Pacansky-Brock on Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

References:

- Nicholas, G., Foote, J., Kainz, K., Midgley, G., Prager, K., & Zurbriggen, C. (2019). Towards a heart and soul for co-creative research practice: a systemic approach. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 15(3), 353-370. ↩

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2017). Service-dominant logic 2025. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(1), 46-67. ↩

- Ulrich, W. (2005). A brief introduction to critical systems heuristics (CSH). ECOSENSUS project site. ↩

Also published on Medium.