Community development in disaster-stricken nations through a knowledge management lens

In this personal reflection for a Master’s course assignment, I examine my past experiences in community development projects with non-profit organisations in disaster-stricken nations through a knowledge management (KM) lens. There were numerous parallels between such projects and KM initiatives. That included the importance of establishing a good reputation as a knowledge contributor to secure stakeholders’ support, and aligning personal and organisational values to sustain project motivation. Success factors such as technology and people should be critically examined and harnessed for future readiness and resilience. Continuous learning, unlearning, and relearning would be expected as we increasingly work in multicultural teams and across contexts. Finally, we should also consider the impact and sustainability of projects – not at completion, but right from the start before it all begins.

In the past decade, community development projects brought me to Cambodia, Laos, then Nepal – beautiful lands scarred by disasters such as civil wars and earthquakes.

where we contributed to the improvement of rural roads.

Source: © Jennifer Koh, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Embarking on such projects in dynamic, foreign environments was no child’s play. It entailed dealing with change, and change was hard.

Knowledge reputation and stakeholders’ support

My risk-adverse parents expressed much resistance to my participation. To them, international issues were beyond their immediate purview. They could not comprehend why individuals would want to volunteer when there were other matters requiring attention at home.

Concurrently, they were sceptical that individuals like me who had only experienced peace and stability would have any relevant know-how to contribute. I had yet to establish a good reputation of a knowledge seller in this area and could not secure their trust. Deep down, I understood this opposition as implicitly stemming from their unspoken love and concern for me.

Such projects were also costly. They demanded significant amount of time, physical labour, and financial resources, among others, from all involved. Much had to be committed, and much had to be sacrificed.

Source: © Jennifer Koh, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

It was not hard to understand why many projects that struggled to secure stakeholder support could not take off.

Strategic alignment of personal and organisational values

Why did I still choose to proceed, then?

In retrospect, I was very much in pursuit of a purpose-driven life, where this purpose entailed supporting humanitarian goals of rebuilding communities and healing lives. This was important to me. It acted as my bearing, steering many of my subsequent decisions such as building a career in the social service sector in Singapore and participating in international community development projects with non-profit organisations.

The alignment of personal and organisational values was critical. On a subjective level, it enabled me to feel meaningfully engaged as I volunteered with like-minded peers. I felt belonged. It kept me going, despite the challenges faced.

Source: © Jennifer Koh, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

On a pragmatic level, the non-profit organisations and communities in-need benefitted from our contributions for as long as we stayed. They needed to attract volunteers with the same values, and sustain them. Otherwise, brain drain and knowledge leaks vis-à-vis volunteer attrition would undermine organisational ability to operate in an efficient, effective, and productive manner to achieve humanitarian goals.

They therefore took great care to check for values alignment from the beginning, through interviews and screening. Thereafter, they sustained volunteers’ motivation and capabilities to contribute through activities such as team bonding sessions and training workshops.

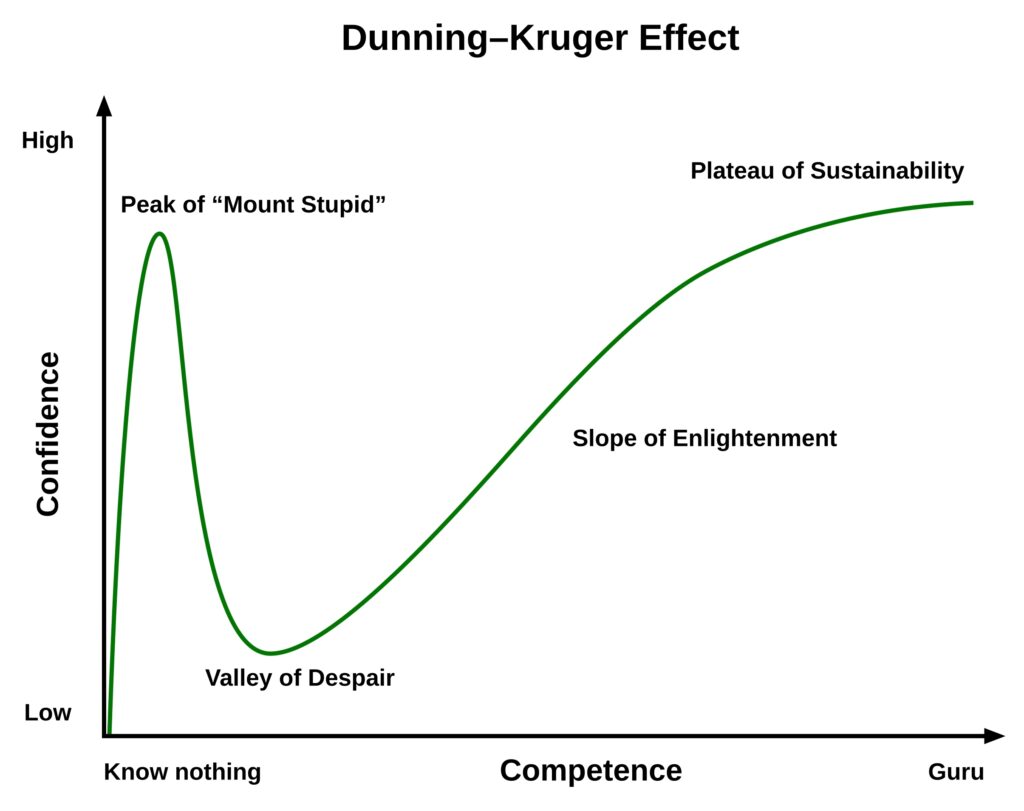

Complacency: confidence > competence

Truth be told, a part of me felt confident to continue with the third trip to Nepal come what may. I saw myself as a knowledge seller, with experience from earlier projects that I could contribute. Furthermore, I had been reading up to acquire new knowledge, and exchanging it with teammates to prepare ourselves. We would also have a senior team leader with prior project experience in Nepal, supported by a Nepali guide and translator. Both of them would be our knowledge brokers, assisting us to navigate the local environment and paving access to social capital and resources.

Oh my, I might have overestimated my skills and competencies. I soon experienced gaps between expectation and reality, and between head knowledge and practice.

Source: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

Things were still manageable when we were in Kathmandu, the capital, as resources were generally within reach. Gaps and unexpected issues increasingly surfaced as we headed off to the village.

So, what happened?

Rethinking technology

Technology was one of those surprises.

It had been such a ubiquitous part of our lives in Singapore that I did not think much about it.

Similarly, in Kathmandu, the mobile phone signal was stable and taken for granted. It enabled our navigation to the market square to obtain logistics, and supported instantaneous communication with loved ones back home. Likewise, it gave online access to codified, explicit knowledge, such as about places where we could purchase additional project supplies.

However, after an eight-hour bumpy ride across mountain peaks and valleys to reach the village of Bhusapheda some 120km away, everything changed.

Bhusapheda was relatively untouched by information and communication technology (ICT). The mobile signal was weak and intermittent. When some of us accidentally headed out to a construction site without an essential tool, we could not simply call or text other teammates to pick that up and bring it along. We had to walk back to retrieve it. How we missed the convenience of ICT!

Source: © Jennifer Koh, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

That aside, a silver lining was that for the first time in a long while, our eyes and attention were hardly glued to screens.

In the daytime, we engaged in long, deep conversations unmediated by technology as we walked and laboured. At night, us city dwellers sat in awe of the beauty of forgotten stars in the night sky.

Future readiness and resilience

That set me thinking about the significance of technology, particularly ICT, in our social and organisational lives. It has been embedded in and intertwined with so many processes that we struggle to imagine a reality without it.

It is almost as though technology = life.

But it is not. Technology is a means to an end, not the end itself. With or without technology, our lives must still go on.

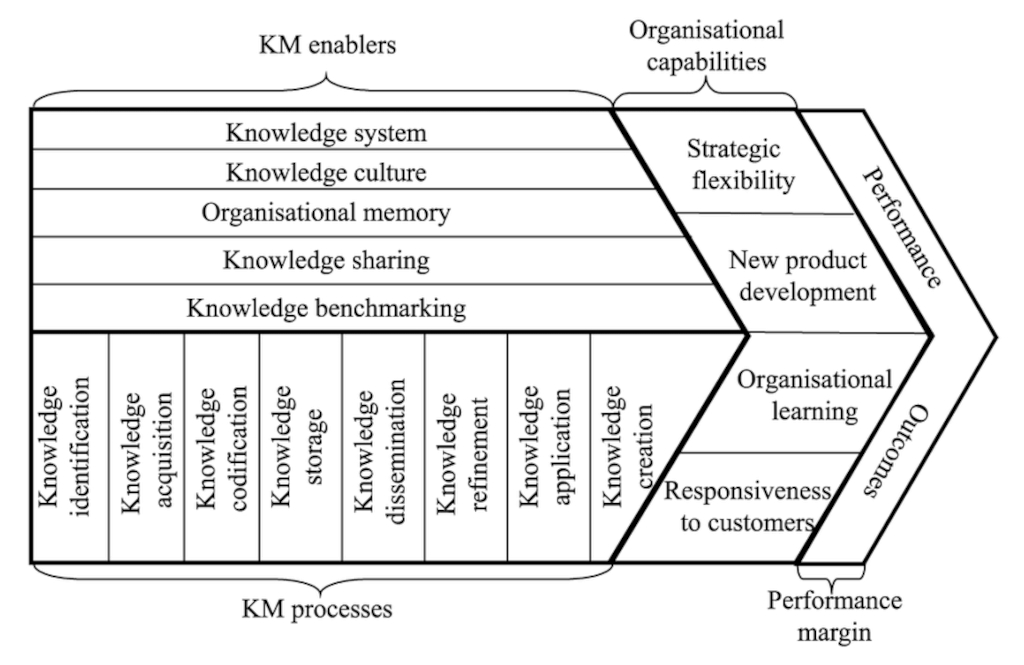

The same applies to knowledge management (KM) initiatives. While technology is a critical success factor1, it is not the only one. KM must remain sufficiently ready and resilient to march ahead. There are other enablers, such as our leadership, culture, strategies, frameworks, and processes that we may harness to drive change and achieve impact.

Source: © Jennifer Koh, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Collective sense-making and learning

What happened if we needed answers to issues or situations new to us?

While we no longer had access to our beloved internet to search for answers, we continued to have each other. And that was good to get us going. Knowledge resides in people; we are our greatest assets.

Individually, we had limited information. When we huddled, we could share our tacit knowledge and open up that space for others to join. They could expand existing ideas or share alternative perspectives. Through such creative dialogue, new collective knowledge was created and we used that to inform decision-making to achieve our shared goals.

That happened often. We exchanged ideas using a mix of English and Nepali, aided by a local translator. With that, knowledge was continuously shaped and contextualised with our understanding of local realities. Solutions were birthed and experimented.

Source: © Mark Yeow, taken for #LoveNepal Team 12, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Sometimes, we succeeded. We celebrated small wins as a team. On other occasions, we struggled. Our team leader played a crucial role in creating a conducive and safe space for learning and continual improvement. He did not point out those struggles as mistakes or failures. He did not push blame. Conversely, he encouraged us to talk about such issues and how that affected us at our during-action reviews. In a participative manner, he facilitated discussions for collective sense-making and solutioning.

For instance, we encountered challenges when trying to install new shower stalls on the challenging terrain. We did not have suitable pipes or water hoses to channel the spring water. Nightfall was approaching, and we needed to get something up and running urgently. After several attempts, we decided to use pails as stop-gap measures. We took a break to regain morale, then regrouped to troubleshoot and refine. We continued to learn by doing and eventually figured it out.

Source: © Mark Yeow, taken for #LoveNepal Team 12, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

In addition, our team leader documented the struggles, enablers, and key learning takeaways at our after-action review. In this process, inputs from the locals were actively sought and considered. These codified insights had permanence, and were shared with the next team so they could take off from a better baseline. They would not have to reinvent the wheel if they encountered similar situations.

Unlearning and relearning

The learning curve was steep, so was the unlearning and relearning curve. This particularly stood out in how we approached “work”.

As our volunteering time in Nepal was limited, many of us wanted to contribute as much as we could. We were task-driven and did not mind working for longer durations with little break. There were so many things to do, but so little time!

Source: © Jennifer Koh, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

When the locals took breaks that were longer than expected, we were caught off-guard.

We asked, “Would you want to complete this quickly too?”.

“There was no rush”, they replied.

With probing, we learnt that the long breaks enabled them to walk home for lunch then nap and recharge, before returning to the work site. This was their routine and norm. Rest was as equally important as work. If they could not complete the work today, there was still tomorrow.

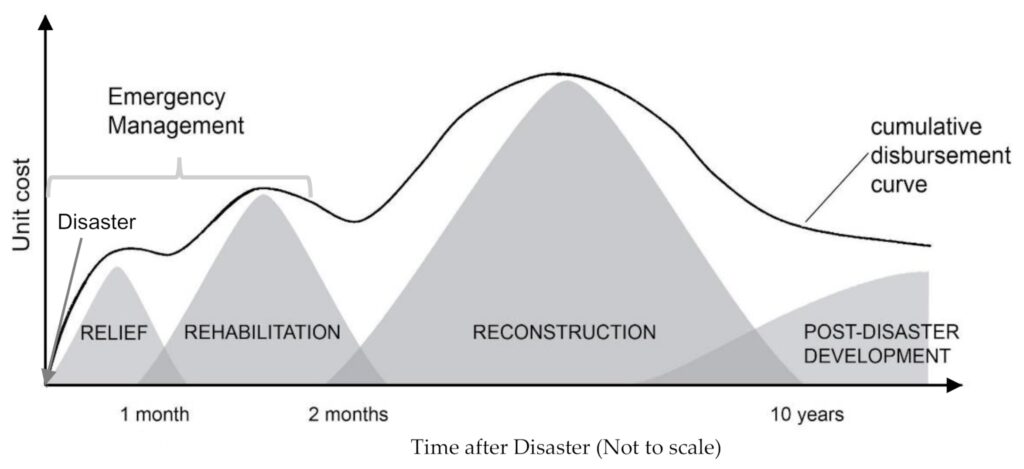

In retrospect, it might be helpful to contextualise this in different lived realities. My raw hypotheses are that: For the locals, their reality comprised long-drawn cycles of earthquakes, followed by post-disaster efforts. These had no clear start or end dates. Post-disaster development work would go on, for long. There was no need to rush.

Source: Chester et al., 20212.

We might not have been as culturally attuned as we aimed to be. That was a blindspot which we had to unlearn and replace with new sensitivities to differences to better function in multicultural teams and across contexts.

In search of impact

I started each project with a desire to make a difference, and I hoped to have achieved it by the time of completion. Yet, this impact oftentimes seemed elusive.

Part of this has to do with the difficulty of operationalising and measuring impact. For example, how do we measure the impact of “rebuilding communities and healing lives?” What standards do we use? Which indicators are included or excluded, and what could be the implications on the conclusions that we make? As hinted by my KM course instructor Rajesh Dhillon, it could help to think about the “value of the change you have brought to the people you visited.”

Without intentional impact monitoring and measurement, how would we know if any change had occurred in our project context? How then could we generate feasible recommendations to scale and sustain this change? Or rally stakeholders’ commitment of continued resources to subsequent iterations?

Turning back time to when it all begins, do we have the core skills and competencies to recognise and define this impact? Do we have access to knowledge resources and enabling systems and structures that we could use strategically to achieve it? How are we harnessing the value of knowledge? What else must we do?

Source: Wang and Ahmed, 20053, cited in Ermine, 20134.

I will leave these open for anyone who is keen to chime in… and for myself too, when I come back to this reflective space someday.

Appreciate any thoughts. In the comments below, let me know if anything speaks to you.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions in this personal reflection are solely mine, and not any of the organisations that I am or may be affiliated with.

Article source: Adapted from Community Development Seen Through Knowledge Management Lens.

Header image: Bhusapheda village, Janakpur zone, Nepal. Source: © Jennifer Koh, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

References:

- Heisig, P. (2009). Harmonisation of knowledge management–comparing 160 KM frameworks around the globe. Journal of knowledge management, 13(4), 4-31. ↩

- Chester M., El Asmar, M., Hayes S., & Desha, C. (2021). Post-Disaster Infrastructure Delivery for Resilience. Sustainability 13(6), 3458. ↩

- Wang, C. L., & Ahmed, P. K. (2005). The knowledge value chain: a pragmatic knowledge implementation network. Handbook of Business Strategy, 6(1), 321–326. ↩

- Ermine, J. (2013). A Knowledge Value Chain for Knowledge Management. Journal of Knowledge & Communication 3(2), 85-101. ↩