How Japan revolutionized football with knowledge

At the 2022 Qatar World Cup, an Asian team shocked the world—Japan. Japan successively defeated Spain and Germany, emerging from the “group of death”. As a long-time loyal fan of the Japanese team, I retrospect the reform journey of Japanese football and discovered its notable emphasis on knowledge management.

1. Start with anime

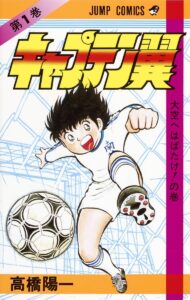

Diverging from the traditional verbal and practical training given by coach, Japan initially propagated football knowledge through anime1. In 1981, Japan decided on a football reform. The Japanese realized that for sports in the country to rise, the “children” were key. That year, a manga2 called “Captain Tsubasa“3 began serialization in Japan’s most popular magazines. Three years later, it was adapted into an animated series and aired nationwide on TV.

“Captain Tsubasa” not only delivered the basics of football techniques and strategies but also showcased the players’ mindset, teamwork, and competitive spirit. Serving as an information medium, it effectively conveyed the culture and knowledge of football to a vast young audience. In 1981, when “Captain Tsubasa” started its serialization, the number of registered football players in Japan was just 68,900. By 1988, when its serialization ended, the figure had surpassed 240,000. In less than a decade, the number of elementary and middle school football teams in Japan almost tripled. The number of elementary school football players registered with the Japan Football Association also increased from 110,000 to 260,000. In 2002, of the 23 players in the Japanese national team that participated in that World Cup, 16 said that they developed a love for football after watching “Captain Tsubasa.”

2. Integrating football with local communities

2.1 Team naming

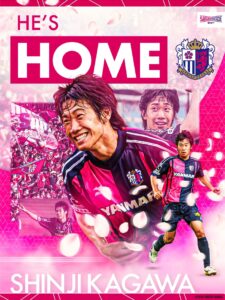

The J-League (Japan’s top professional football league) introduced a concept of “community-based” football. The J-League requires all football clubs to avoid corporate sponsor names and instead adopt a “region + nickname” naming format to give every citizen a sense of belonging and identification. Japan believes that while companies might change, clubs bearing the names of locales will better integrate with the community.

Whether related to local fauna, flora, food, or even hot springs, anything could be taken as a team name—like “Shimizu Heartbeat” from Shizuoka, symbolizing the heart’s excitement when one thinks of football; “Osaka Sakura” and “Kitakyushu Sunflower” carry the names of city flowers; “Kashima Antlers,” aiming to be loved like a deer by locals while its sharp antlers point towards victory; port city teams often associate with the sea: Yokohama Mariners, Kobe Victory Ship, Nagoya Orcas, and Zanpier Kamatama Sea.

2.2 Stadium is more than a pitch

In J-League, each club’s main stadium is referred to as its “hometown.” The pitch belongs to the people; teams have no proprietary rights over it. Every year, the J-League officially publishes a hometown activity survey report, detailing what each club has done in the past year—a report every resident has the right to download and view for free. In April 2021, the J-League released a detailed 128-page activity survey, detailing how each club conducted its hometown activities, integrating “community” with “football.”

Such activities are tailored to local characteristics and closely aligned with community residents’ lives. For example, in Akita Prefecture, which has the highest aging rate, club players exercise and walk with the residents, and the club’s nutritionists prepare nutritious lunches. In flood-prone Yamagata Prefecture, football clubs collaborate with the fire brigade to establish flood prevention systems. The “Urawa Red Diamonds,” named after roses, plant roses in city parks with the locals as a gesture of gratitude.

All these efforts not only unite local communities but also sow the seed in countless children’s hearts that “football is a beautiful sport.”

3. School football

Looking at the sports growth systems worldwide, only Japan’s dual-track system is impeccable. This dual track means club youth training + school football. The key lies with the latter—school football. From elementary school to university, every school has a comprehensive training system, professional football pitches, and matches. Kids can be students while being professional football players, without hindering their academic degree.

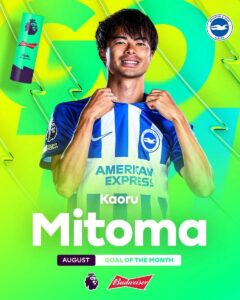

It might be hard to imagine, but the “Japanese High School Championship” is one of the most popular sports events in the country. It’s evident that Japanese school football is highly professionalized. Most Japanese players come from the “Japanese High School Championship,” and their performance in this event attracts professional club contracts. Players can also choose to delay signing and further their studies in universities. Since university teams are on par with professional clubs, their skills won’t diminish. After graduation, they can still become professional players. Mitoma, who recently shone brightly with Brighton & Hove Albion in the English Premier League, became a professional player only after completing his studies at Tsukuba University.

The advantage of this approach is if players can’t sign with a professional club due to their limits or injuries, they can still seek regular jobs based on their educational qualifications. Parents also feel reassured, agreeing to let their children pursue football. In contrast, in Europe and South America, players lack skills outside football. Once eliminated, it’s too late to return to university.

4. Youth training philosophy

Japan divides the youth football training into different stages, clearly defining the objectives and content for each stage. This structured knowledge management method ensures that players receive appropriate training and support at every developmental age. Japan splits youth football training into five stages:

- ages 8-9 as the enlightenment period

- ages 10-15 as the basic technique and tactics learning and transitioning to practical matches period

- ages 16-17 as the practical match period

- ages 18-21 as the maturity period

- ages 21 and above as the completion period.

Japanese football believes that the human nervous system develops the fastest when a child enters primary school, with the brain already achieving 90% of an adult’s capacity. However, body muscles and stamina aren’t sufficient, making them prone to injuries. For young kids and early-grade primary students, the first step is to let them enjoy the sport, maintain focus, train briefly but intensively, acquiring more skills and body memory during the period of rapid neural development, emphasizing “accuracy over power.”

Junior high is a tricky phase. Exceptional primary school players might suddenly decline, while an average child might start to excel. Coaches should help maintain and improve their current capabilities and stabilize their psychological state. Generally, preschoolers up to 5 years primarily “play,” developing an interest in outdoor activities. Primary school onwards, they cultivate a good judgment and feel for football, emphasizing football technique and mental fortitude during junior high and later.

Thus, the primary mission during the elementary and junior high stages is to cultivate student interest in football, teach basic techniques and tactics, and participate in appropriate-level matches. The high school phase’s main goal is to solidify skills through real matches and prepare for the selection of outstanding football talents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the reform of Japanese football utilized knowledge management principles effectively. Through structured training, cultural promotion, and community engagement, Japan successfully enhanced football’s popularity and standards. Plus, I sincerely hope that Japan’s neighbor—my homeland China—can learn from these successful knowledge management examples and save struggling Chinese football4.

Article source: Adapted from How Japan Revolutionized Football with Knowledge, prepared as part of the requirements for completion of course KM6304 Knowledge Management Strategies and Policies in the Nanyang Technological University Singapore Master of Science in Knowledge Management (KM).

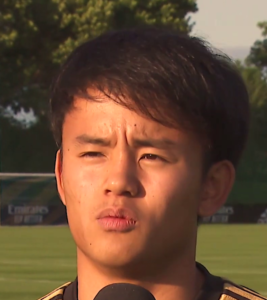

Header image source: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0.

References:

- Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0. ↩

- Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0. ↩

- Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0. ↩

- AFP. (2024, January 23). Chinese fans round on national team after Asian Cup ‘disaster’. Yahoo Sports. https://uk.sports.yahoo.com/news/chinese-fans-round-national-team-083840069.html. ↩