Tacit knowledge is no longer the preserve of humans

Tensions within the study and practice of knowledge management (KM) have long been an issue. At one end we have debates around some of the more philosophical questions such as what is information and knowledge, how do they differ and can we actually capture the tacit knowledge held in human brains and codify it within an information system? At the sharper, implementation end, the field of KM is littered with systems and solutions that over-promised and under-delivered. However, the rise of AI-based KM offerings raises some fundamental questions that could overturn many of the core tenets underpinning KM.

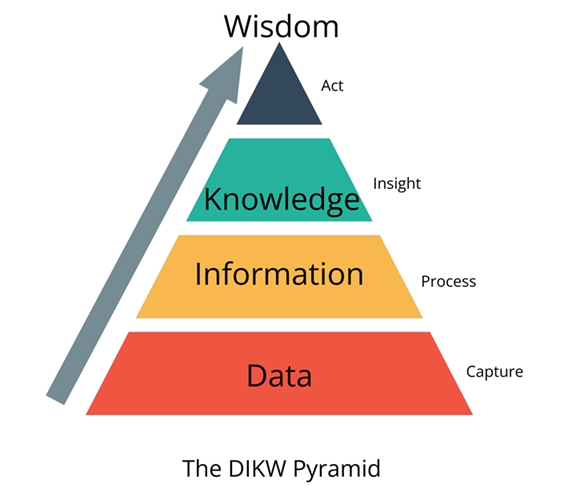

Although taken less seriously than it once was, the data, information, knowledge, wisdom (DIKW) pyramid offers a useful way of conceptualising the way raw inputs of data are transformed into actionable insights that can guide the actions of organisations. Technology has traditionally been more concentrated at the first levels of the pyramid through the capture, processing and making sense of raw data1 as well as organising and presenting information in ways understandable by humans.

The knowledge element has typically been a mix of the codification of human tacit knowledge and machine-generated actionable insights such as predictive scoring and forecasting. While a rather nebulous term in the context of KM, wisdom has usually been seen as the individual and collective learning accrued from the three other stages.

AI has the potential to upend this process and remove human inputs out of KM altogether in many instances. A recent paper2 in the journal Knowledge defined tacit knowledge as “the individual knowledge obtained through experiential learning and processed by the cognitive unconscious part of the brain.” Wisdom is defined by Jashapara3 as “the ability to act critically or practically in a given situation” Recent advances in AI have seen machines taking over these hitherto human activities in a number of situations.

Writing in Wired magazine4, David Weinberger points to the growing discord between computers operating to rules and models created by humans and those that are acting in a far more autonomous manner, “Advances in computer software, enabled by our newly capacious, networked hardware, are enabling computers not only to start without models – rule sets that express how the elements of a system affect one another – but to generate their own, albeit ones that may not look much like what humans would create. We are increasingly relying on machines that derive conclusions from models that they themselves have created, models that are often beyond human comprehension, models that “think” about the world differently than we do.”

A prime example is Google’s AlphaGo that beat the Go world champion in 2016 in a game that has far more possible moves than chess. Using a deep learning approach combined with a neural network, AlphaGo made winning moves never previously used by any human players and radically transformed our understanding of the game through the creation of new knowledge.

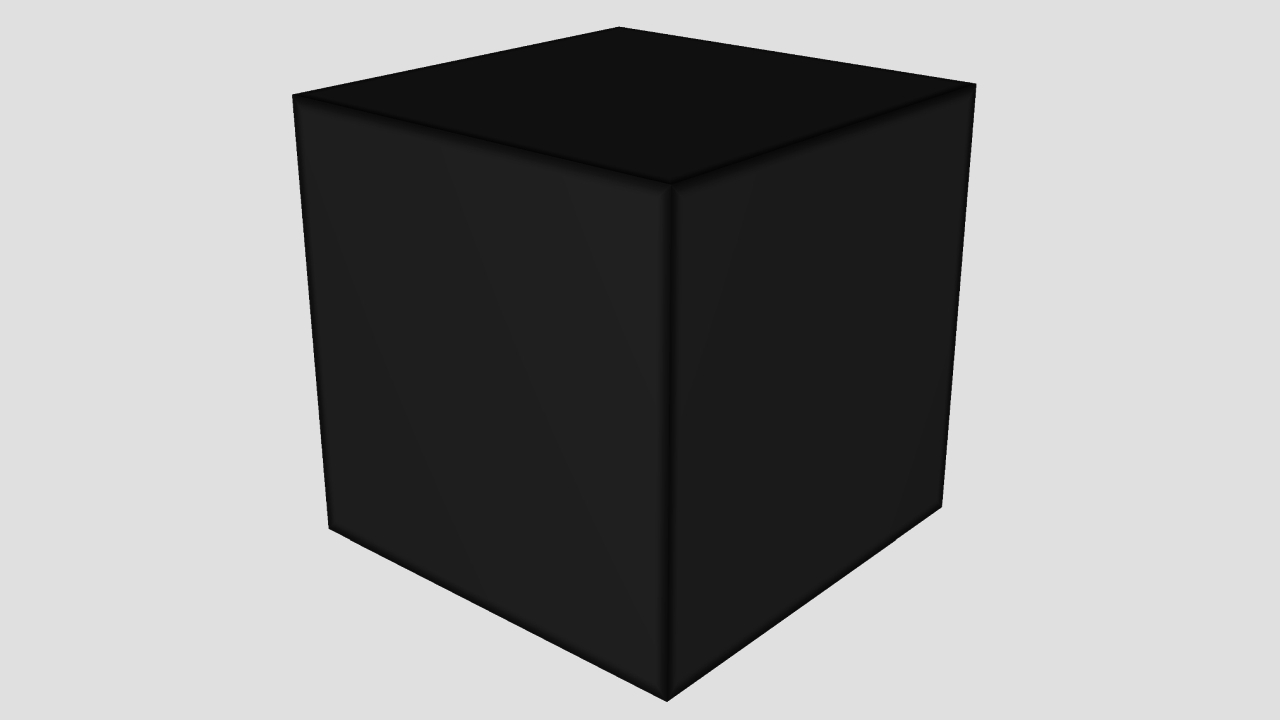

Here lies the potential problem for KM programs and the firms deploying them. As more decision making is devolved to computers using AI, the creation of knowledge and wisdom will increasingly be held within machines rather than the humans working in these organisations. The reasoning behind the outputs of large language models via products such as ChatGPT are a mystery to users but also to many of the AI programmers that created them. We risk handing over an organisation’s collective knowledge and wisdom to black boxes that lack transparency and accountability for their actions.

Trying to capture tacit knowledge from human actors will no longer be the challenge for KM developers and practitioners. The focus will be attempting to understand the “knowledge” and “wisdom” held within these black boxes and how it came to be created.

Header image source: 35393 on Pixabay.

References:

- Davenport, T. H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge: How organizations manage what they know. Boston: Harvard Business Press. ↩

- Bratianu, C., & Bejinaru, R. (2023). From Knowledge to Wisdom: Looking beyond the Knowledge Hierarchy. Knowledge, 3(2), 196-214. ↩

- Jakubik, M., & Müürsepp, P. (2022). From knowledge to wisdom: will wisdom management replace knowledge management?. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 31(3), 367-389. ↩

- Weinberger, D. (2017, April 18). Our Machines Now Have Knowledge We’ll Never Understand. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/our-machines-now-have-knowledge-well-never-understand/. ↩