The relationship between science and art [Arts & culture in KM part 9]

Often seen as opposites, science and art both depend on observation and synthesis.

This article is part 9 of a series exploring arts and culture in knowledge management.

When C P Snow, the British novelist and physical chemist, wrote in 1959 that “the intellectual life of the whole of Western society is increasingly being split into two polar groups”, he was talking of the differences between scientists and literary intellectuals. But he could as easily have been talking about science and the visual arts.

To many, science embodies the rational and analytical end of human experience, while art comes from the empathic and expressive. Science can prove truths to us, while art can only make us feel them.

These differences are compounded as science becomes responsible for the official narrative of our lives, through medicine and genetics, while contemporary art retains a mystical ‘outsider’ status, both in its intellectual obscurity and the inflated prices of the international art market. Nevertheless, where science meets art and the two work together, the result can be extraordinarily productive, as horizons are broadened and gaps in our understanding of both are filled.

In the 20th century, science has revolutionised art’s means of production, from the introduction of fast-drying polymer-based acrylic paints in the 1960s, to the ubiquity of computer-based image generation today. Science has also offered us a key to some of the traditional mysteries of artistic practice. For example, Dr John Tchalenko’s ‘painter’s eye’ project attempted to demystify the way in which a painter transfers the image of a model to paper by tracking eye and hand movements to discover the length of an artist’s visual memory: the time during which he or she can maintain the image in the mind as it is transferred to paper or canvas.

Science also provides aesthetic inspiration. In 1951, at the Festival of Britain, the Festival Pattern Group combined post-war optimism about both science and design. Textile, wallpaper, ceramic and other material designs were produced based on recent developments in X-ray crystallography, a technique that reveals the complex internal structure of chemical and biological substances. The designs pervaded the Festival, on London’s South Bank, including the wallpaper of the Regatta restaurant, but in the absence of mass production the styles never became widely popular.

In return for such advances, artists have often lent their services to promote the understanding of science. As anatomy became increasingly important to medicine in the 18th century, but cadavers to examine were in short supply, wax model making came into its own as a means of instructing both medics and the general public in the workings of the human machine.

Joseph Towne, the official model-maker at Guy’s Hospital in London, made over 1,000 anatomical models, some of which were on display in Exquisite Bodies, in his 50 years at the hospital. Even today sculptors like Eleanor Crook produce educational models that show in three dimensions what photography can’t.

We can now see what blood vessels, vitamins and cancer cells look like. Sometimes this requires direct collaboration between scientists and artists. Dave McCarthy and Annie Cavanagh produced an image of a fly on sugar crystals for which McCarthy operated an electron microscope to produce a black-and-white image, after which the colour was added by Cavanagh.

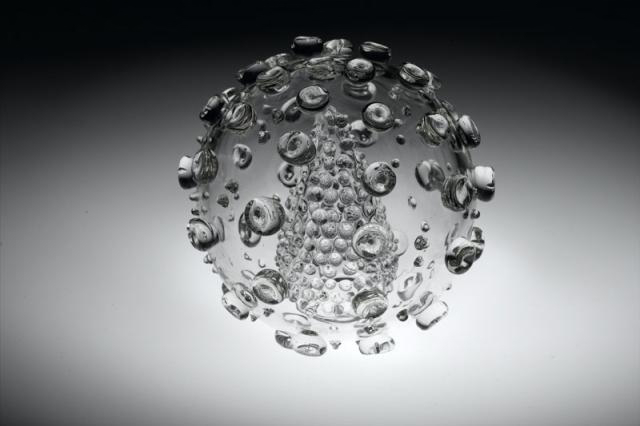

Though such images can be both beautiful and instructive, adding artificial colour to scientific images can be controversial. Luke Jerram’s series of blown-glass sculptures of viruses such as HIV and H1N1 present the microbes as transparent, devoid of any of the colour.

Jerram (who is himself colour-blind) feels that the artificial and garish colouring of images communicates unnecessary fear. His elegant and complex structures confer not only simplicity, but also some kind of beauty to widely reviled pathogens.

Science and art both rely on observation and synthesis: taking what is seen and creating something new from it. Our society could hardly exist without either, but when they come together our culture is enriched, sometimes in unexpected ways.

Article source: The relationship between science and art, Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0. Republished by permission.

Header image: From Luke Jerram’s series of blown-glass sculptures of viruses. Source: Wellcome Collection, © Luke Jerram, CC BY 4.0.