The psychology behind knowledge hiding in organisations

This article is part of a series on knowledge withholding, hiding, and hoarding.

Research that I summarised1 in September 2020 recommended further investigation into the personal and contextual factors likely to significantly influence engagement in knowledge collection, knowledge donation, knowledge hiding, or knowledge hoarding behaviours. These personal and contextual factors were then explored in a paper2 published earlier this year.

Now, a newly published paper3 in the journal Administrative Sciences describes a study that has sought to understand the psychological process behind the knowledge hiding behaviors of employees in organisations. To do this, study authors Roksana Binte Rezwan and Yoshi Takahashi synthesized 88 previous studies on knowledge hiding through a systematic literature review. They then used the cognitive–motivational–relational (CMR) theory of emotion to create a framework for the review findings.

Knowledge hiding is defined as an intentional attempt by an individual to withhold or conceal knowledge that has been requested by another person. It takes place among coworkers, team members, and even between supervisors and subordinates.

Cognitive–motivational–relational (CMR) theory of emotion

Previous studies have used various variables and a range of theories to explain the relationships between those variables and knowledge hiding. These theories include construal theory, theory of knowledge stickiness, social exchange theory, conservation of resources theory, social learning, and psychological ownership theory.

However, Rezwan and Takahashi contend that while the richness of variables explored is useful for enhancing an understanding of knowledge hiding, those theories are not comprehensive enough to understand the overall picture. They advise that cognitive–motivational–relational (CMR) theory has advantages for understanding the psychological process behind knowledge hiding, based on its explicit identification of the role of emotion in this process. CMR theory is a theory of emotion, in which cognitive, motivational, and relational aspects are crucial to generating the emotions expected to cause an action.

CMR theory proposes 15 different emotions, along with their relational meanings. The meaning generation process for an event varies from person to person depending on their unique goals, motives, and desires. Further, meaning generation for an event has two underlying processes – primary appraisal and secondary appraisal.

Primary appraisal

In primary appraisal, people evaluate the person–environment relationship. People appraise whether an event has personal meaning to them in three ways. First, they identify whether the event is related to any of their goals (goal-relevant); second, they evaluate whether the event will take them further away from the goal or bring them closer to it (goal congruence); and, finally, they evaluate the content of the goal (goal content). Primary appraisal is unconscious, automatic, and involuntary; and involves identifying whether an event is harmful, threatening, challenging, or beneficial. Sometimes this primary appraisal is enough to cause a person to react with a particular emotion. For example, appraising an event as a threat might lead to anxiety. However, there may be a secondary appraisal before the individual experiences any emotions.

Secondary appraisal

Secondary appraisal, which is conscious, deliberate, and volitional, adds a more detailed evaluation of the person–environment relationship. There are three characteristics of a secondary appraisal. The first is blaming oneself or others with respect to an event; specifically, considering whether the event is non-directed or how much of it can be blamed on or credited to oneself or others. Blaming oneself or others is associated with anger, whereas being unable to direct blame at anyone in particular can lead to sadness. The second characteristic is coping potential, which is an individual’s confidence in being able to control a situation. The third characteristic is future outcome expectation. People evaluate whether acting in a certain way will bring them closer to their goal or take them further away from it.

Secondary appraisal is related to coping mechanisms. In problem-focused coping, a person copes with the situation by influencing the person–environment relationship. If that is not possible, then the individual brings about internal change or tries to see the situation differently to cope with the emotion, which is termed emotion-based coping,

CMR theory explains the psychological process behind knowledge hiding

Based on CMR theory, how an individual responds to a knowledge request depends on that person’s goal. In other words, a person (i.e., her/his goal)–environment relationship creates an emotional reaction that, in turn, leads to knowledge hiding.

The same sort of relationship can also be found in the original generation process of the person’s goal. In that initial process, a person–environment relationship is determined by internal attributes (person) and external attributes (environment). To this end, Rezwan and Takahashi propose that the integrated process of how knowledge hiding manifests can be better explained by dividing the process into two parts – the goal generation process of the individual in the organisational context and the knowledge-request event appraisal process, both of which have a CMR process of their own.

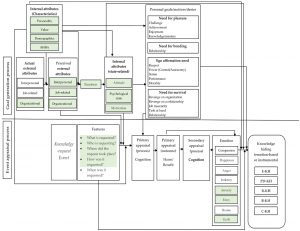

The integrated framework is shown in Figure 1. The goal generation process happens over time and arises from internal and external attributes. During a knowledge-request event, how the person appraises the features of the event depends on the person’s goal and the person–environment relationship in the goal generation process. The manifestation of knowledge hiding in the knowledge-request event is mediated by a process of primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, and emotion.

Goal generation process

When people join an organisation, their perceptions regarding actual external attributes (that is, colleagues, responsibilities, and the organisation itself) depend on their characteristic-related internal attributes (that is, personality, values, demographic characteristics, and abilities).

The types of emotions that employees experience in everyday work life arise from experiencing those perceived external attributes and their own characteristic-related internal attributes. Those overall emotions influence employees’ attitudes regarding the organisation, their psychological state, and motivation, which are state-related internal attributes (with primary and secondary appraisals for every occasion).

These attributes, along with characteristic-related internal attributes, guide the individual towards developing specific goals in the organisation. Those goals can be dispositional or dynamic depending on the situation.

A hierarchy of six goals has been proposed in CMR theory: affiliation, power/achievement, personal growth, altruism, stress avoidance, and sensation making. Rezwan and Takahashi developed an elaborated list of goals applicable in the context of knowledge hiding. They broadly categorised those goals into four types according to an employee’s needs within the organisation: pleasure, bonding, ego affirmation, and survival. The sources of these needs are rooted in basic biological needs.

An individual might be motivated to engage in workplace knowledge hiding for a range of possible personal goals broadly comprised by that list. For example, employees may derive pleasure from activities, achievements, challenges, or learning something new. People often feel the need to connect or bond with their coworkers and supervisors. Employees need to feel autonomous, esteemed, and valued, although some people might simply want to be respected, whereas some people might want to be acknowledged for their power, status, performance, knowledge, or moral values. During a knowledge request encounter, goals based on these needs might cause the employee to engage in knowledge hiding. Further, employees need a feeling of overall job security, which may sometimes express itself as taking revenge, and may also motivate knowledge hiding.

Knowledge-request event appraisal process

An individual’s goals establish the essential background context from which an employee appraises a knowledge-request event and manifests knowledge hiding. Based on CMR theory, Rezwan and Takahashi propose that a knowledge-request event can be interpreted differently by individuals through their cognitive appraisal processes. How an employee appraises the knowledge-request event first depends on which goal is most important to them at the time of the request, as well as internal and external attributes (stable person–environment relationship).

Moreover, Rezwan and Takahashi also note that the various features of the knowledge request may ultimately lead to knowledge hiding. A knowledge sharing request event includes five significant features based on who, what, when, where, and how questions. From these questions and the stable person–environment relationship (internal and external attributes), an employee evaluates whether the knowledge request is related to their personal goal and if the goal is at stake or not. From the primary appraisal process, the employee can immediately decide whether sharing knowledge will be harmful or beneficial to the goal, which is a cognitive process.

Any knowledge-request event appraised as harmful or beneficial will engender an emotional response. In the CMR theory-based framework, Rezwan and Takahashi have incorporated eight major emotions based on their relevance to a knowledge-request event: happiness, compassion, anger, jealousy, anxiety, envy, guilt, and shame. When individuals perceive the knowledge request as beneficial, they experience positive emotions, such as compassion or happiness. If they perceive it as harmful or threatening, negative emotions, such as anger, jealousy, anxiety, envy, shame, and guilt, may arise. An employee’s cognitive appraisal process can also include a secondary appraisal leading to an emotional response. In the secondary appraisal, the individual may think about how they might respond or cope with the knowledge-request event.

As shown in Figure 1, the emotions felt after the appraisal process drive the employees to manifest knowledge hiding as evasive knowledge hiding (E-KH), playing dumb knowledge hiding (PD-KH), rationalised knowledge hiding (R-KH), bullying knowledge hiding (B-KH), or counter questioning knowledge hiding (C-KH). This depends on the personal goal at stake, the features of the knowledge-request event (situation), and the stable person–environment relationship (internal and external attributes). In general, positive emotions lower knowledge hiding and negative emotions, such as envy, increase knowledge hiding. However, some negative emotions like guilt may also reduce knowledge hiding.

Employees’ knowledge hiding behavior can be either emotion-based or instrumental. Employees may engage in emotion-based knowledge hiding when reacting to the knowledge-request event; an emotion-based response is unconscious and derived from the feelings of the moment. An instrumental response, unlike reactional emotion-based responses, is consciously derived from the emotion felt in the situation.

It is important to understand that whether knowledge hiding is an unconscious or a conscious drive originates from the emotion experienced. If it is an unconscious drive, we can suggest solutions to help individuals understand the root of their knowledge hiding responses. If it is an instrumental response, we can direct our attention to the person–environment relationship or elements of the external attributes and internal attributes that might be responsible for an employee’s conscious drive to hide knowledge.

Rezwan and Takahashi advise that the CMR framework can be used to explain the relationships found in previous studies. For example, previous studies have explored how abusive supervision may increase knowledge hiding. When assessing the response to a simple knowledge request by a coworker, it may not be immediately clear how an abusive supervision event influences an employee’s knowledge hiding behavior with a coworker; however, the goal generation and knowledge-request event processes help in understanding this relationship.

The process starts when the employee perceives the supervisor’s behavior according to their own internal attributes, which leads to emotional responses such as anger or anxiety. These emotions may make the employee feel insecure about their job or feel betrayed by the employer (a psychological contract breach), which may lead to a desire to protect their job or to feeling vengeful toward the organisation. This may generate the goals of “protecting job” or “revenge.” Therefore, when a knowledge-request event occurs, the employee appraises the situation in light of the “protecting job” or “revenge” goals. This cognitive appraisal process may cause anger or anxiety and lead to knowledge hiding through the emotion-based (unconscious) or instrumental (conscious) response processes.

CMR theory can also explain how the appraisal processes of an individual deciding to hide knowledge affects the dimensions of knowledge hiding. For example, if employee X is working to meet a deadline, at that moment, the goal is “task at hand,” a survival need. If employee X is feeling burnt out with the primary goal of completing the task before the deadline, and employee Y makes a knowledge request, the knowledge request can be appraised as a threat to employee X’s goal, causing anxiety.

As a coping potential, if employee X is confident that they can hide knowledge, they may demonstrate deceptive knowledge hiding, such as evasive hiding or playing dumb. On the other hand, if employee X has high organisational identification, they may think that a knowledge hiding act will hamper their fellow employee’s image of them (ego) and affect that relationship negatively. Therefore, employee X may choose to manifest rationalised knowledge hiding instead of evasive hiding or playing dumb.

Among the three types of knowledge hiders, the rationalised knowledge hider is more shrewd because they handle the knowledge hiding situation diplomatically. The rationalised knowledge hider can both hide the intention of hiding and maintain an excellent relationship with the knowledge seeker. Therefore, even though employee X experiences anxiety, the E-KH and PD-KH tendencies may be lower, while the R-KH tendency may be higher when the need for bonding is stronger than the survival need.

Article source: The Psychology behind Knowledge Hiding in an Organization, CC BY 4.0.

Header image source: krakenimages on Unsplash.

References:

- Silva de Garcia, P., Oliveira, M., & Brohman, K. (2020). Knowledge sharing, hiding and hoarding: how are they related? Knowledge Management Research & Practice, DOI: 10.1080/14778238.2020.1774434. ↩

- Strik, N. P., Hamstra, M. R. W., & Segers, M. S. (2021). Antecedents of Knowledge Withholding: A Systematic Review & Integrative Framework. Group & Organization Management, 1059601121994379. ↩

- Rezwan, R. B., & Takahashi, Y. (2021). The Psychology behind Knowledge Hiding in an Organization. Administrative Sciences, 11(2), 57. ↩

Also published on Medium.