Co-creative approaches to knowledge production and implementation series (part 5): Case study of a co-creative approach to providing technical assistance

This article is part 5 of a series of articles based on a special issue of the journal Evidence & Policy.

In the first of the papers in the research section of the special issue, Yazejian and colleagues1 from the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explore the use of a co-creation approach when providing technical assistance to Head Start regional centres.

A national programme in the United States, Head Start has promoted school readiness by enhancing the social and cognitive development of children through the provision of educational, health, nutritional, social, and other services to enrolled children and families.

A large national technical assistance centre has provided technical assistance to Head Start regions to strengthen their use of implementation science in the application of evidence-based practices to improve outcomes for children and families served by Head Start programmes. Implementation science has been defined as the study and application of methods and processes designed to support achievement of a programme or activity that has clearly defined components.

The goal of the Head Start technical assistance was ‘to advance best practices in the identification, development, and promotion of the implementation of evidence-based development and teaching and learning practices that are culturally and linguistically responsive and lead to positive child outcomes across early childhood programs’.

In its administration of technical assistance to regions, the national centre has used a ‘co-creation’ model. Co-creation is the active involvement of stakeholders in all stages of the production and implementation process resulting in service models, approaches, and practices that are contextualised and tailored to settings. Over a two-year period, three Head Start regions identified a set of improvement objectives, and the national centre used a responsive, co-creation technical assistance approach to support the regions in meeting their objectives.

Co-creative technical assistance approach

Yazejian and colleagues advise that technical assistance approaches can vary along dimensions related to dosage2, delivery methods, and levels of collaboration.

Knowledge of best practices for the provision of technical assistance is at an early stage. Generally, a higher dose of technical assistance has been found to relate to greater improvements in capacity and/or implementation. Both in-person and virtual technical assistance can be effective, but generally on-site technical assistance, compared to technical assistance that is telephone- or email-based, has been shown to be more likely to lead to chances for experiential learning and demonstration of skills. The quality of the collaborative relationship between technical assistance providers and participants has emerged as critical to successful implementation of practices.

Co-creation approaches to providing technical assistance have emerged as an important component of effective and sustainable implementation capacity building. Through co-creation, recipients and beneficiaries of technical assistance are actively involved in all stages of planning and implementing the technical assistance resulting in models, approaches, and practices that are contextualised and tailored to their settings. The goal of contextualisation is to ensure there is a match between technical assistance and the values, needs, skills, and resources of those delivering interventions, systems stakeholders, and service beneficiaries.

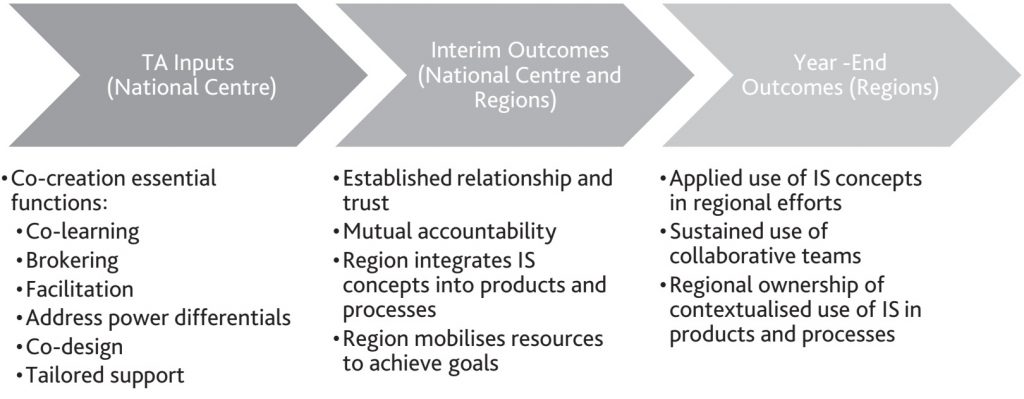

The co-creative technical assistance approach examined by Yazejian and colleagues was designed to strengthen the integration and application of implementation science concepts in the Head Start regions in order to increase capacity for the service and systems changes needed to enable the use of evidence-based approaches. There is increasing attention in the academic literature to specific competencies needed to facilitate implementation and evidence use. As shown in Figure 1, the co-creative technical assistance approach for the current project relied on a model of change that specified essential functions and interim and project-end outcomes.

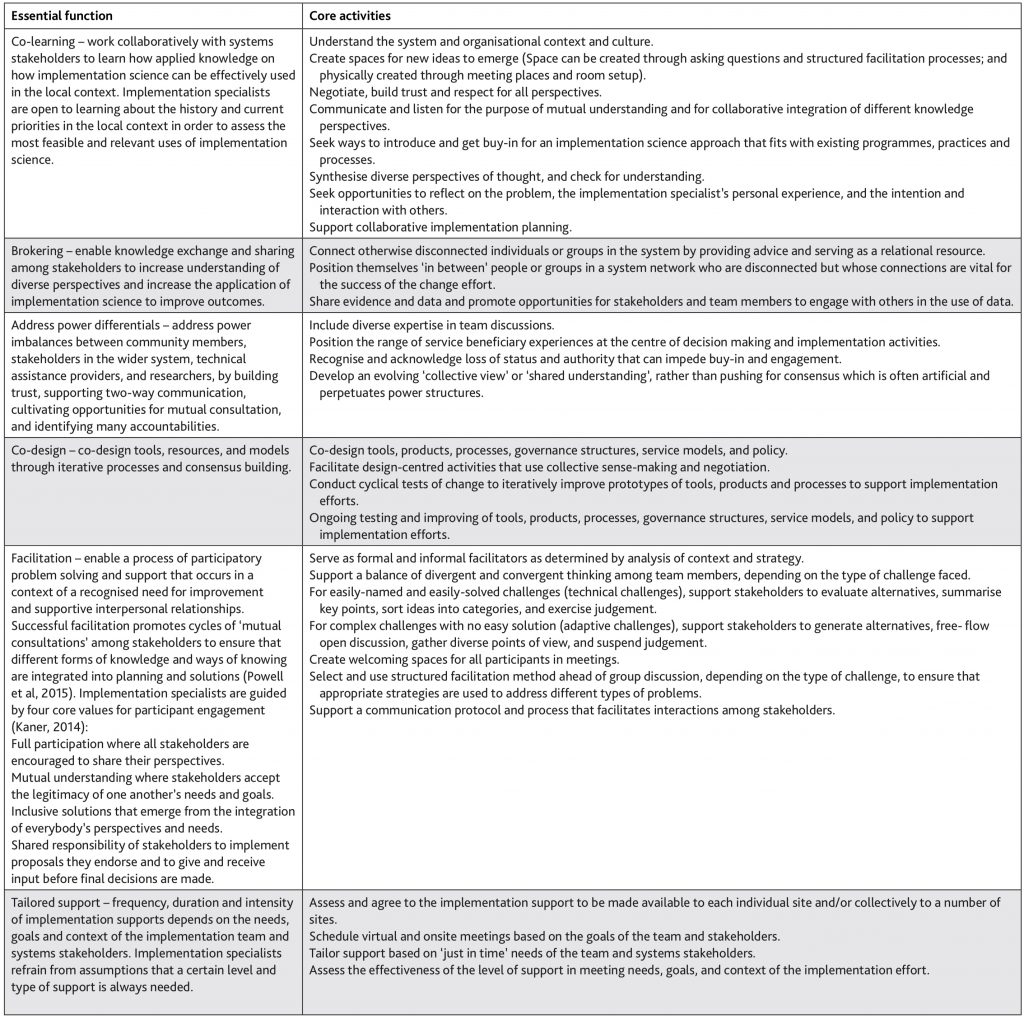

As detailed in Figure 2, the essential functions that supported co-creation included co-learning, brokering, facilitation, addressing power differentials, co-design, and tailored support, with each of these defined as part of a practice profile for the implementation specialists delivering the technical assistance.

The three regions that participated in the project began with a strong interest and readiness to engage the technical assistance staff to help build their implementation capacity. Each region identified a core team that would participate in technical assistance activities and communicate and coordinate with regional staff beyond the core team. Each region also identified one or two specific areas of need for technical assistance support that were individualised for their region.

One region (Region A) expressed an interest in a virtual webinar series that would most efficiently engage their core and broader staff in learning about implementation science principles, while the other two (Regions B and C) each expressed interest in a more intensive technical assistance approach that would help to further assess specific needs within their broader interest of incorporating implementation science principles into their grantee support processes.

From the beginning of the process with the regions, the technical assistance team used the co-creative approach by first discussing roles and expectations with each region using a ‘Give and Get’ activity that attempted to set the stage for shared expectations and clear roles. This was designed to allow each region to arrive at a shared agreement with the technical assistance staff on what regional staff would contribute to the technical assistance process (through participation and development work), and what to expect from the technical assistance staff (through guidance and facilitation).

The technical assistance staff also used initial meetings to assess current capacity with the regions, and facilitated discussions on identifying next steps in their work. These specific activities were not prescribed but emerged out of a co-creative process with each region.

Over the two-year period, the technical assistance staff met in-person and virtually and communicated electronically with regional staff in the provision of technical assistance . Each meeting and interaction, and the frequency with which they occurred, was tailored to the region’s needs and goals. For example, in-person meetings were scheduled when the region felt as though they would benefit most from the in-person support. Tailored support can be contrasted with traditional technical assistance models that prescribe the dosage of support prior to the engagement with the recipient.

Participant experiences and interim outcomes

Data gathered for the purposes of informing the technical assistance were analysed by Yazejian and colleagues as secondary data for their paper. Three sources of data – observation, survey, and listening session – were summarised to determine whether the technical assistance providers succeeded in delivering technical assistance that was co-creative.

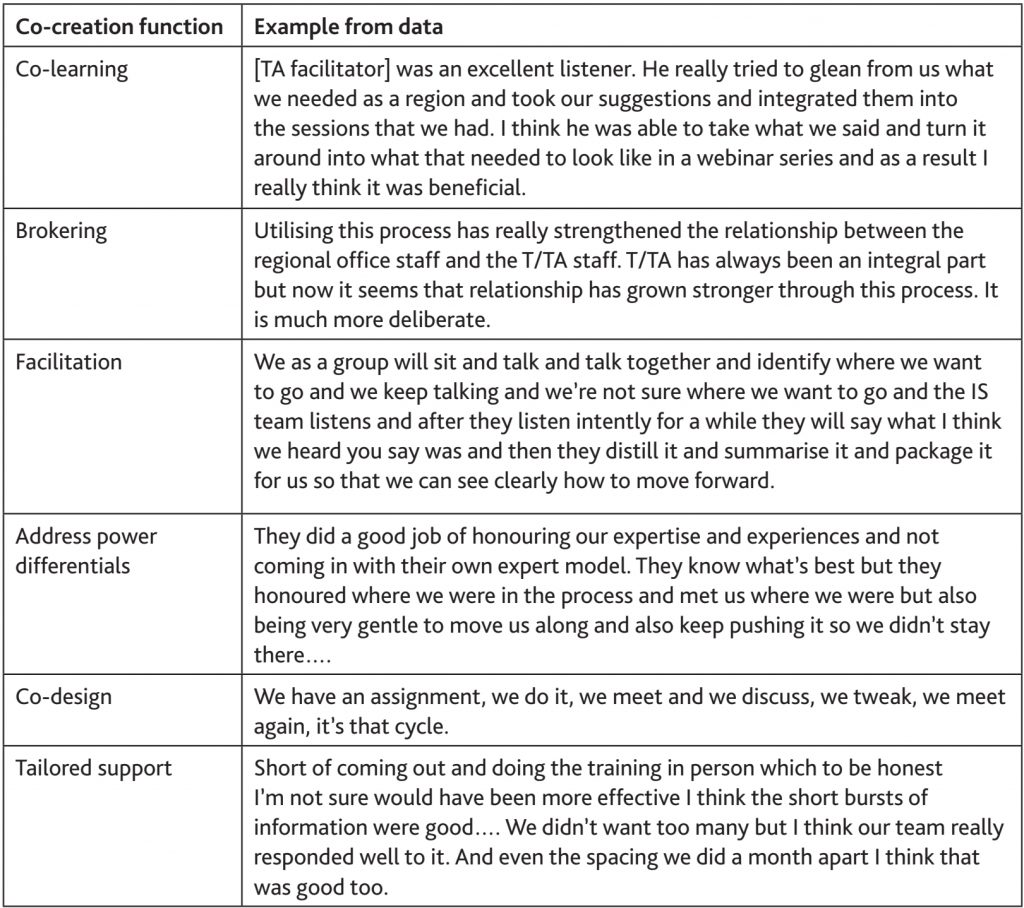

All three sources of data suggested that the technical assistance providers delivered technical assistance that actively involved participants and was contextualised and tailored to each region’s needs. Facilitation was mentioned most frequently for regions B and C, while tailored support was mentioned most frequently by participants in region A. Co-learning was the second most mentioned category overall, after facilitation. Figure 3 provides an example from the data of each of the co-creation essential functions as reported by participants during the listening sessions.

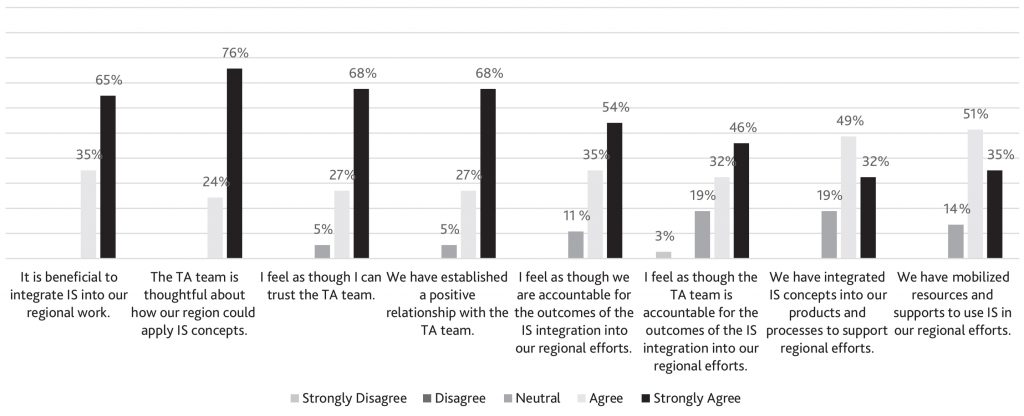

Data from the listening sessions supported the achievement of interim outcomes. Figure 4 presents survey data, which demonstrate that participants generally agreed or strongly agreed that trust was established, there was mutual accountability in the work, and integration of implementation science was beneficial to regional work. There was less strong agreement that implementation science concepts were integrated into regional products and processes.

Support for co-creation

Yazejian and colleagues state that their small-scale study provides initial evidence that using a co-creation approach in the delivery of technical assistance is achievable and can be associated with positive outcomes.

Using existing data from multiple sources, the analyses showed that the technical assistance providers succeeded in delivering technical assistance that was perceived by both observers and participants as involving participants and being tailored to their settings and needs. Evidence also suggested that the interim outcomes of trust, mutual accountability, and some integration of implementation science concepts into ongoing regional work were achieved.

Previous research has found that in general, higher doses of technical assistance have been related to greater improvements in capacity and implementation. In the current examination, the frequency and dosage of service provided was relatively low overall and was particularly low for region A, which requested virtual technical assistance. Even with this low dosage, a co-creation technical assistance approach was successfully delivered and was related to interim outcomes.

The study is small, and additional evidence is needed; nevertheless, as funds for professional development have become more limited, finding effective virtual delivery mechanisms that do not rely solely on didactic approaches will be critical. A co-creation approach that is tailored to recipients’ needs shows promise as one that works for both in-person and virtual delivery of technical assistance, and should be further explored for evidence of effectiveness across providers and domains.

Yazejian and colleagues advise that their study fills a need in the literature by examining technical assistance that was delivered within the confines of a specific framework, namely co-creation. It also provides a specific definition of co-creation functions that corresponds to competencies needed to facilitate use of implementation strategies. Within this co-creation framework, evidence suggests that the three different regions in this analysis may have experienced different levels of each of the co-creation components, based on mentions during listening sessions and coding of observation data.

Since each region identified different goals in collaboration with the technical assistance consultants, the mentions of specific co-creation activities would not be expected to be the same across regions. Rather, the mentions for specific co-creation activities highlights the specific focal areas of the work with each region and the tailoring of services to needs. For example, technical assistance consultants working with Region C focused their efforts largely on facilitating a process with the Region C implementation team leadership, so it is not surprising that facilitation was mentioned more often than the other categories of co-creation. In comparison, Region A work was delivered virtually via webinar and therefore included a larger proportion of didactic content relative to the other regions; that facilitation was mentioned less often aligns with the focus of the activities that were conducted with Region A.

Next part (part 6): What qualities and considerations should characterise co-creative research?

Article source: Adapted from the paper Co-creative technical assistance: essential functions and interim outcomes published in the Evidence & Policy special issue Co-creative approaches to knowledge production: what next for bridging the research to practice gap?, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Acknowledgements: This series has been made possible by the publication of the special issue as open access and under a Creative Commons license. The guest editors and paper authors are commended for their leadership in this regard.

Header image source: Adapted from an image by Michelle Pacansky-Brock on Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

References and notes:

- Yazejian, N., Metz, A., Morgan, J., Louison, L., Bartley, L., Fleming, W. O., … & Schroeder, J. (2019). Co-creative technical assistance: essential functions and interim outcomes. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 15(3), 339-352. ↩

- The amount and frequency of technical assistance given. ↩

Also published on Medium.