The case for indigenous knowledge systems and knowledge sovereignty (part 9): Knowledge systems of the Beni-Amer

This article is part 9 of a series of articles putting forward the case for indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) and knowledge sovereignty, featuring selected excerpts from the book Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders.

The description and analysis of indigenous pastoral knowledge and practice among the Beni-Amer have shown that this knowledge provides a sustainable livelihood for pastoral communities, contributing increased productivity as well as resilience in the face of environmental and political stresses. Comparisons with other pastoralist knowledge systems illustrate how these communities incorporate their own knowledge into their local livelihood strategies and integrate some aspects of western veterinary knowledge into their practice.

The Beni-Amer herders attach great importance to good management practices that enhance animal health and productivity. Their pastoral production practices have been systematically refined over time, as is evidenced by their having a production system which is scientifically sound. They understand the close relationship between livestock production, herd management and animal health, and have an awareness of how these three factors influence each other; this makes them successful professional herders. I have a high regard for this pluralism of knowledge.

As well as the technical and scientific skills of the Beni-Amer, their day-to-day work and their practices of cattle husbandry demonstrate their unique relationship with the land and with the animals, which is embedded in cultural and spiritual values. These understandings determine their milking and breeding practices, their herd composition and management, and their seasonal movements. The fact that they share veterinary knowledge with other pastoralist groups in the study area shows that they have an interest in improving the ways in which they care for their livestock, and that they are open to other methods and techniques. They are therefore in a good position to be the focus of research on ethnoveterinary knowledge and practices, and they can make a significant contribution to livestock research and to pastoral development more widely.

This combination of management strategies, breeding and herding techniques, and animal health is part of a complex yet rigorous knowledge system which is dynamic and adaptive, and encompasses the Beni-Amer’s cultural and ecological understanding of their environment. This means they are well placed for an uncertain future. This adaptiveness and resilience future-proofs them against a range of stresses, such as climate change, unfavourable government policies, natural resource conflicts, land grabbing, biodiversity loss and cattle raiding, and these threats are set to increase and intensify.

Although IK is negotiated by communities and adapted in response to experience, it also incorporates western science, in particular veterinary knowledge. The clash of paradigms between indigenous and scientific knowledge systems is evident in some of the policy decisions that have been made over recent decades. As demonstrated by the practices of the Beni-Amer cattle herders, IK is pluralistic, replicable and dynamic. It is not static, but is ever evolving through observation and practice. Its flexibility and adaptiveness make the case to sustain and build on IK, and this should be seen as a policy and research priority as we go forward into an uncertain future.

Pastoralists have generations of collective knowledge and experience of adapting to ecological and socio-economic changes, and have developed an immense wealth of indigenous knowledge and practices to deal with these changes. Their indigenous knowledge system is dynamic and characterised by flexibility and adaptability and is strongly integrated into their socio-cultural system. It is not easy to distinguish these practices from more recent processes of local innovation, which is equally a reflection of flexibility and adaptability. It is, however, important to give attention to local innovations, whether they are in response to climate change or to other changes, because they are sources of valuable new knowledge based on the deep-rooted experience of pastoralists1.

This adaptive nature of IKS means that practices can move with the times and be supplemented with modern technology, in particular in food production, so that new technologies such as genetic modification (GM) are not the only solution to food insecurity.

Pastoral communities around the world adapt to challenges on a daily basis to ensure their livelihood. They endure marginalisation and political alienation, as their mobility is crucial for their survival. There are many lessons to be learnt from the resilience of these communities as we all face new and emerging threats from climate change and globalisation. The case studies show how their IKS is evolving to deal with common challenges such as resource-based competition and conflict. Diversifying their economies has impacted on their social and cultural structures and threatens some of their traditional knowledge. Their ethno-botanical knowledge may be lost as they become less mobile and resources dwindle, and it is clear that agro-pastoral communities must all become involved in the conservation and management of plants, and medicinal plants in particular2.

Next part (part 10): Moving the debate forward.

Article source: Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

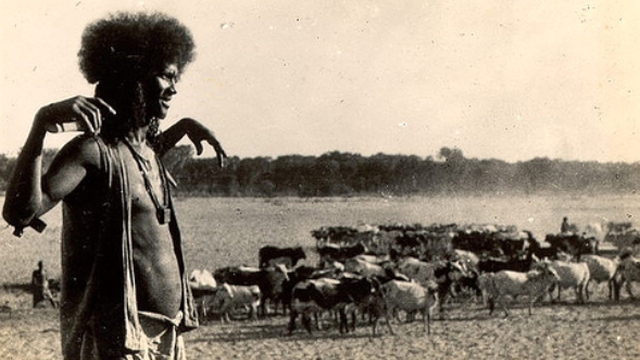

Header image source: Tigre man from Barka Valley is in the Public Domain. The Beni-Amer people probably emerged in the fourteenth century AD from the intermixing of the Beja and the Tigre.

See also: Cultural awareness in KM.

References:

- GebreMichael, Yohannes, Saidou Magagi, Wolfgang Bayer and Ann Waters-Bayer. 2011. ‘More than Climate Change: Pressures Leading to Innovation by Pastoralists in Ethiopia and Niger.’ Paper presented at the International Conference on the Future of Pastoralism, 21–3 March, organised by the Future Agricultures Consortium at the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex and Feinstein International Center of Tufts University. doi:10.1.1.417.2119. ↩

- Fenetahun, Yeneayehu. and Girma Eshetu. 2017. ‘A Review on Ethnobotanical Studies of Medicinal Plants Use by Agro-pastoral Communities in Ethiopia.’ Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies 5(1): 33–44. ↩