The future of knowledge management: an agenda for research and practice

From time to time, academic journals publish notable reviews looking at the past and future of knowledge management (KM). Previous such reviews include Johannes Schenk’s 2023 systematic review1 which identified eight emerging innovative concepts in KM, and Alexander Serenko’s 2021 structured literature review2 of scientometric research of the KM discipline.

The findings of reviews like these are very important for KM practice. For example, some of the eight emerging innovative concepts in KM identified in Schenk’s review are receiving much less attention from KM practitioners than others, which is a concern, and the significant implications flowing from Serenko’s review include the need to consider that KM may exist as a cluster of divergent schools of thought rather than a single discipline.

Now, coinciding with its 20th anniversary, the journal Knowledge Management Research & Practice (KMRP) has published a new narrative review3 titled “The future of knowledge management: an agenda for research and practice.” KMRP is focused on the interplay between research and practice, so the findings of the review are of particular relevance to evidence-based practice in KM. The first issue of KMRP was published in May 2003, and the twentieth volume at the end of 2022. The review is authored by John Edwards and Antti Lönnqvist, who are both members of the KMRP Editorial Board.

In this RealKM Magazine article, I summarise Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review and raise further important perspectives in additional commentary, including alerting to significant issues that I consider are missing from the review. The structure of sections 1 to 5 below is as follows:

- Sections 1 and 2: Edwards and Lönnqvist first look at selected past KM activity, including descriptions, predictions, initiatives and other research agendas.

- Section 3: Edwards and Lönnqvist state that their review looks backwards only in order to look forward, so they then merge their retrospective into a consideration of the current states of KM literature and KM practice, raising some issues that they consider need to be taken into account for the future.

- Section 4: Finally, Edwards and Lönnqvist synthesize an agenda that they contend is focused on research on practice, not just research and practice.

- Section 5: I alert to significant issues that I consider are missing from Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review.

1. What is KM?

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- KM is a broad area, with contributions from many different disciplines.

- There is still no generally agreed definition of KM. On the one hand, this is not necessarily a problem, as artificial intelligence faces the same issue but is not being held back by it. On the other hand, it makes it harder to explain KM, its benefits and its challenges to others, whether they are people outside the field or those who might possibly be encouraged to join it.

- Non-specialists find it difficult to appreciate the added value of KM for their managerial work because KM literature deals with somewhat technical tasks related to knowledge, whereas managers deal with general management type challenges.

- Authors often show a curious reluctance to be precise about what they mean by KM. It has been argued that KM authors ought to present an ‘operational definition’ of KM, but there are many different definitions of KM and knowledge, and a study found that two-thirds of the KM papers considered did not define their terms fully.

2. Looking backwards to look forward

2.1. Past descriptions of KM

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- There are numerous descriptions of the state of KM, and/or how KM got into that state, including the theoretical background to KM.

- Four main clusters of topics were identified in a 2020 bibliometric analysis of KMRP literature4:

-

- Knowledge sharing, including knowledge transfer and knowledge exchange, and also covering trust and organisational support (the largest cluster).

- Knowledge management itself, including tacit knowledge, codification and innovation.

- Intellectual capital, including social capital, relational capital and knowledge asset.

- Social networking, absorptive capacity, networked innovation, supply chain and collaboration (the smallest cluster).

-

2.2. “Pre-KMRP” predictions about the future of KM

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- In 1997, the person generally credited with popularising the term KM, Karl Wiig5 thought that over a decade or two, KM would be assimilated into the daily mainstream work and become ‘second nature’.

- In 2001, another of the pioneers of KM, Larry Prusak6 thought that KM would either go in the direction put forward by Wiig, or alternatively have no legacy because it would be hijacked by sales representatives and sloganeers.

- This does not seem to have happened, but currently in most organisations, KM has not become a natural part of how people organise work. There has been much work on standards: for example ISO 30401:2018, but KM does not seem to be as widely known or used as might be hoped.

- Two studies made different predictions in regard to KM based on artificial intelligence (AI): a 2000 study by Smith and Farquhar7 that was very optimistic, and a 2001 study by Liebowitz8 that offered more measured reasoning.

- KM has not had a major impact on libraries, despite the prediction that it would become increasingly important.

Bruce Boyes’ commentary:

- It’s not surprising to see the newly emerged Global Organizational Think Tank on Tacit Knowledge Management (GO-TKM) seeking to chart a new path for KM, given that what has been known as KM has not become a natural part of how people organise work, and also the less than positive state of KM as raised by Edwards and Lönnqvist in sections 1 above and 3.1 below.

- Liebowitz’s more measured reasoning in regard to KM and AI has proven to be a more accurate prediction, with the KM community only now paying widespread attention to AI, more than 20 years after Liebowitz’s paper. However, this attention is unfortunately in large part reactive in response to the hype surrounding the release of ChatGPT rather than through proactive strategy. This aligns with the issue of a lack of breakthrough developments in KM raised by Edwards and Lönnqvist in section 3.1 below, with Liebowitz in 2001 as uncertain as Prusak about whether KM had a future.

2.3. Past research agendas

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- Many authors have offered their view of a KM research agenda.

- Perhaps the most comprehensive attempt by Heisig and colleagues9 came up with eight very broad themes: business strategy, intellectual capital, decision-making, knowledge sharing, organisational learning, innovation performance, productivity, and competitive advantage.

- Some of these themes had already been extensively researched. Heisig and colleagues made the point that that this shows KM is such a broad and complex field that experts were not aware of all of the research that had been done. But it could also be argued that KM scholars themselves need better KM.

Bruce Boyes’ commentary:

- KM practitioners are apparently just as unaware of the current broad themes of KM as are KM researchers. Illustrating this, I’ve encountered in recent times leading experts in the organizational KM theme who are unaware of the extensive work that has been and continues to be done on the KM for development theme. This aligns with the issue of most published KM research focusing on

the organization, as raised by Edwards and Lönnqvist in section 3.5 below. Organizational KM and KM for development are distinct enough areas of focus to warrant considersation as potentially seperate disciplines of KM.

2.4. Past initiatives

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- Many authors have suggested frameworks for KM practice, as it is after all one of the things that academic authors do in the hope of making a name for themselves.

- Arguably more usefully, Liebowitz10 offered five specific practical suggestions for the early days of KM in an organisation: run a series of KM forums; conduct a knowledge audit of a targeted area; attend KM seminars and conferences; bring in KM advisors to shape a KM strategy; and develop a repository for best practices/lessons learned/“yellow pages”.

- These would still be well worth following for any organisation that has never engaged with KM.

- Others have proposed more specific directions in which KM should assist and/or develop, such as ‘sensible organisation’ by incorporating more creativity and diversity into structures, processes and human resources.

- There has also been the suggestion that editors and business schools should provide room for discussions of research findings between scholars and stakeholders, as well as calls for more problem-driven KM research.

3. Aspects and issues

3.1. Is KM dying?

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- Authors remained obsessed for a very long time with whether or not KM was a fad that would soon disappear, until analyses such as those of Wallace and colleagues11 and Serenko and Bontis12 laid that to rest.

- However, concern about whether or not KM is dying continues in the wider KM community.

- One possible cause for this is that there have not been many breakthrough developments in KM research in recent years. Much of the research is about making minor additions to what is already known, and many articles are still relying on well-known models such as Nonaka’s SECI model13 as their starting point. At the same time, some related disciplines such as analytics, big data, and artificial intelligence are developing very quickly.

- Another possible cause is the extent to which KM is actually practiced in organisations seems unclear; is KM a real organisational activity or mainly an academic exercise?

- A specific relevant issue is that there are very few published studies looking at the long-term effectiveness and/or impact of KM.

- Another issue to consider is that knowledge-related research themes have become popular within many established research fields. As this is the case, we may question whether a specialised research field of KM is still needed.

Bruce Boyes’ commentary:

- If it becomes widely successful, the newly emerged Global Organizational Think Tank on Tacit Knowledge Management (GO-TKM) could well mean that KM as we’ve known it is actually in its death throes, and also undergoing a much-needed rebirth. This is because GO-TKM is seeking to invigorate a new worldwide movement with a clear focus on just tacit knowledge management (TKM), against the backdrop of the less than positive state of traditional KM, as raised by Edwards and Lönnqvist in this section and sections 1 and 2.2 above.

- While undoubtably a very valuable perspective put forward by a highly respected pioneer in KM, it’s getting harder to ignore the long-held and growing criticisms of the evidence for and general applicability of Nonaka’s SECI model, for example as expressed by Gourlay and Nurse14 and Adesina and Ocholla15. Models from the earliest days of KM remain the focus when there are newer models drawing on the extensive body of research and practice knowledge that has since emerged. For example, David Williams’ action-knowledge-information (AKI) model16 is a highly coherent alternative to Ackoff’s data-information-knowledge-wisdom (DIKW) model17,18. AKI has been in existence for nearly a decade, but DIKW remains the overwhelming focus. This lack of evolution in the theoretical basis for KM practice means that it has stagnated and become increasingly irrelevant, as raised by Edwards and Lönnqvist in this section and sections 1 and 2.2 above.

3.2. Repeating the same mistakes

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- In 1998, Fahey and Prusak19 outlined the eleven deadliest sins of knowledge management:

-

- Not developing a working definition of knowledge.

- Emphasizing knowledge stock to the detriment of knowledge flow.

- Viewing knowledge as existing predominantly outside the heads of individuals.

- Not understanding that a fundamental intermediate purpose of managing knowledge is to create shared context.

- Paying little heed to the role and importance of tacit knowledge.

- Disentangling knowledge from its uses.

- Downplaying thinking and reasoning.

- Focusing on the past and the present and not the future.

- Failing to recognize the importance of experimentation.

- Substituting technical contact for human interface.

- Seeking to develop direct measures of knowledge.

-

- The eleven sins are still a useful ‘memory jogger’. Progress has been made on some of the sins, such as knowledge flow and tacit knowledge, but as Edwards and Lönnqvist raise in section 1 above, the lack of common definitions remains an issue.

3.3. KM and other new(ish) technologies

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- AI without effective KM is a waste of effort and money, with recent research by Leoni and colleagues20 showing that the effect of AI on manufacturing firm performance is fully mediated by KM processes. This is a really important result that deserves to be more widely known and replicated in other contexts.

- There remains scope for much more work on KM and AI, for example the uses of generative AI systems based on large language models.

- Most existing research in the big data literature does not seem to have been informed by KM concepts at all, although there have been a few examples of KM concepts being used in big data.

3.4. Problem-driven research

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- There is an issue about publishing problem-driven research in journals. A common form of problem-driven research is action research, but writing these studies up comprehensibly within the length typically allowed for a journal paper proves to be impossible. This needs to be overcome.

- The majority of submissions to KMRP nowadays are questionnaire-based statistical studies. Some may be considered mechanistic and repetitive with only marginal additions to existing knowledge, even though many are of high quality and provide novel findings. Problem-driven research can also provide novel findings that are relevant to practice.

3.5. Scope

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

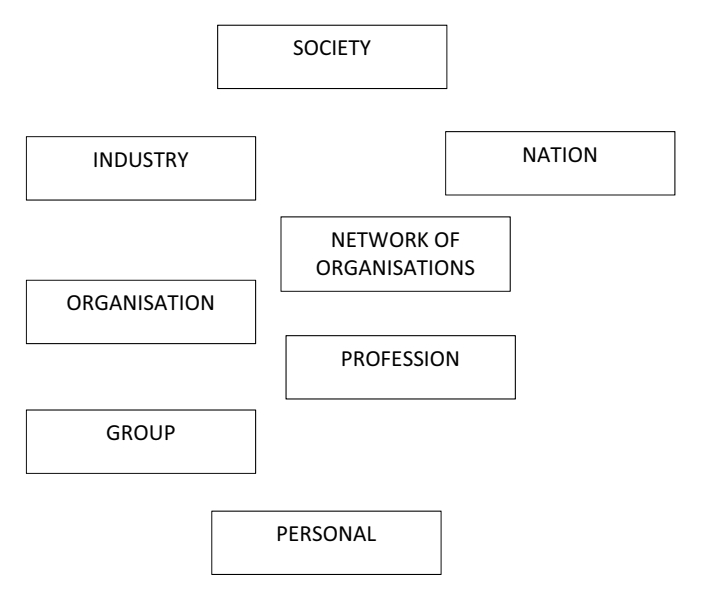

- KM can operate on several levels, including at least those shown in Figure 1.

- The placing of the levels is indicative, and is not clear-cut, and linkages have been omitted deliberately to avoid blinkered thinking.

- It could be argued that the focus of KM research on the organization has been taken too far, with most published KM research having this focus.

- Within organizations, trying to do KM at the group level can be more of a hindrance than a help – the classic criticism relating to organizational silos.

- There are wider societal implications of what an organization does.

- All KM needs to be grounded in personal KM, as all aspects of KM, including organizational KM, can be seen as stemming from the personal relevance of KM.

- The gap between academics and practitioners appears to have widened since 2013, with Serenko’s landmark 2021 review21 identifying that there is a need for knowledge brokers that may deliver the KM academic body of knowledge to practitioners.

Bruce Boyes’ commentary:

- There is some relationship between Edwards and Lönnqvist’s levels of KM in Figure 1 and my previous proposal that KM may exist as a cluster of divergent disciplines rather than a single discipline.

3.6. Fake knowledge

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- There are two related issues here, stemming from misinformation and disinformation, the latter being deliberate.

- Knowledge issues arising from misinformation cover three overlapping aspects: out-of-date knowledge, knowledge drawn from misleading data, and weak knowledge.

- Disinformation is intentional fake knowledge, and lifts the discussion about KM to a political and societal level. Nowadays, many people seem to reject institutional knowledge and become ‘Facebook or YouTube experts’.

- The use of propaganda (fake stories) to change how people think and to advance one’s political goals are most apparent at the personal, national and societal levels of Figure 1, though they do also appear at the industry level, as with the past actions of the oil companies with respect to climate change.

- There is also a small and very specific problem of deliberately fake knowledge in organisations – but that is one more within the orbit of ethics or criminal behaviour than KM.

Bruce Boyes’ commentary:

- Edwards and Lönnqvist’s raising of fake knowledge as a key issue for the future of KM is highly significant. It is the first notable discussion of this issue in the KM research literature since Steven Alter’s important 2006 paper22 “Goals and tactics on the dark side of knowledge management.”

- In addition to misinformation and disinformation, the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) also defines malinformation, with these three information activities together having the acronym MDM23:

– Misinformation misleads. It is false, but not created or shared with the intention of causing harm.

– Disinformation deceives. It is deliberately created to mislead, harm, or manipulate a person, social group, organization, or country.

– Malinformation sabotages. It is based on fact, but used out of context to mislead, harm, or manipulate.

4. Agenda

4.1. For those doing research

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- More research on what KM achieves – its impact on practice (UK academics and some others will already be feeling this impulse).

- More research that is not biased towards ‘the organization’.

- Progress towards a set of common processes, even if there will be no agreed definition.

- Don’t let the AI opportunity slip by: AI desperately needs KM, even if its practitioners do not realize it themselves.

- More research on what KM actually is in organizations (or elsewhere in society). Who is doing KM in practice and what is it that they are doing?

- More papers linking KM to some new phenomena. Nowadays, there are more papers about KM and sustainability. Perhaps there could be papers connecting KM and societal security or resilience.

4.2. For journal editors and reviewers

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- Insist that authors make it clear what they mean by KM, and perhaps by knowledge as well.

- The “so what” test – what will we do differently in future now that we have the result of this research?

- Be open-minded for new ideas and approaches even if the technical or methodological characteristics of the studies are different from what we are used to.

4.3. For those in and around KM

Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review:

- Talk it up, don’t talk it down.

- Diversity of perspectives is a strength, not a weakness.

- The key work has not always received the attention it deserves (except during the 1990s), even though the wider literature shows the importance of KM.

- More interesting research that questions established conclusions is required. Is what we have said interesting enough, we wonder?

Bruce Boyes’ commentary:

- In response to Edwards and Lönnqvist’s final question of “Is what we have said interesting enough, we wonder?”, my response is “absolutely!” Edwards and Lönnqvist’s KMRP review “The future of knowledge management: an agenda for research and practice” that I’ve summarized here is a most interesting landmark paper, and I’m very pleased to be able to help to communicate it to the wider KM community.

5. What’s missing?

Bruce Boyes’ commentary:

While Edwards and Lönnqvist’s review is comprehensive, there are three critical issues that I see as missing from section 3 above:

- Evidence-based KM: As documented in RealKM Magazine, evidence-based practice is vital for the credibility of KM, so it can help to reverse the less than positive state of KM raised by Edwards and Lönnqvist in sections 1, 2.2, and 3.1 above. It also has a critical role to play in bridging the research to practice gap identified by Edwards and Lönnqvist in section 3.5 above.

- Decolonization of knowledge: As I’ve previously alerted, the KM community needs to play a more active role in progressing the decolonization of knowledge and KM. This is already happening in the KM for Development (KM4Dev) community, which is playing a leading role in decolonization, as highlighted by our recent landmark paper24. However, the organizational KM aspect of the KM community is comparatively doing very little. Change is needed, and KM journals have a significant role to play in helping to facilitate this change.

- Open access journals: As I’ve previously highlighted, reiterated, and reported25, it will be impossible to effectively bridge the gap between KM research and practice while KM practitioners are unable to access KM research findings because they are hidden behind academic journal paywalls. While there are certainly significant challenges in bringing about universal open access, it has to happen so these challenges must be overcome. I suggest that the editors of KM journals convene an open access summit where they explore concrete actions to facilitate open access to all KM journal articles.

Header image source: Javier Allegue Barros on Unsplash.

References and notes:

- Schenk, J. (2023). Innovative Concepts within Knowledge Management. Proceedings of the 56th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 4901-4910. ↩

- Serenko, A. (2021). A structured literature review of scientometric research of the knowledge management discipline: a 2021 update. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25(8), 1889-1925. ↩

- Edwards, J., & Lönnqvist, A. (2023). The future of knowledge management: an agenda for research and practice. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 21(5), 909-916. ↩

- Schiuma, G., Kumar, S., Sureka, R., & Joshi, R. (2023). Research constituents and authorship patterns in the knowledge management research and practice: A bibliometric analysis. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 21(1), 129-145. ↩

- Wiig, K. M. (1997). Knowledge management: where did it come from and where will it go?. Expert systems with applications, 13(1), 1-14. ↩

- Prusak, L. (2001). Where did knowledge management come from?. IBM systems journal, 40(4), 1002-1007. ↩

- Smith, R. G., & Farquhar, A. (2000). The road ahead for knowledge management: an AI perspective. AI magazine, 21(4), 17-17. ↩

- Liebowitz, J. (2001). Knowledge management and its link to artificial intelligence. Expert systems with applications, 20(1), 1-6. ↩

- Heisig, P., Suraj, O. A., Kianto, A., Kemboi, C., Arrau, G. P., & Easa, N. F. (2016). Knowledge management and business performance: global experts’ views on future research needs. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(6), 1169-1198. ↩

- Liebowitz, J. (2001). Knowledge management and its link to artificial intelligence. Expert systems with applications, 20(1), 1-6. ↩

- Wallace, D. P., Van Fleet, C., & Downs, L. J. (2011). The research core of the knowledge management literature. International Journal of Information Management, 31(1), 14-20. ↩

- Serenko, A., & Bontis, N. (2013). The intellectual core and impact of the knowledge management academic discipline. Journal of knowledge management, 17(1), 137-155. ↩

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14-37. ↩

- Gourlay, S., & Nurse, A. (2005). Flaws in the “engine” of knowledge creation. Challenges and Issues in Knowledge Management, 293-251. ↩

- Adesina, A. O., & Ocholla, D. N. (2019). The SECI Model in Knowledge Management Practices: Past, Present and Future. Mousaion, 37(3). ↩

- Williams, D. (2014). Models, metaphors and symbols for information and knowledge systems. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 10(1), 80-109. ↩

- Ackoff, R. L. (1989). From Data to Wisdom. Journal of Applied Systems Analysis, 16, 3-9. ↩

- Nikhil Sharma identifies a number of other people as having put forward earlier conceptualizations of DIKW, but Russell Ackoff is considered to have pioneered DIKW in KM. Ackoff’s model had the additional layer of ‘understanding’, that is, data-information-knowledge-understanding-wisdom. ↩

- Fahey, L., & Prusak, L. (1998). The eleven deadliest sins of knowledge management. California management review, 40(3), 265-276. ↩

- Leoni, L., Ardolino, M., El Baz, J., Gueli, G., & Bacchetti, A. (2022). The mediating role of knowledge management processes in the effective use of artificial intelligence in manufacturing firms. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 42(13), 411-437. ↩

- Serenko, A. (2021). A structured literature review of scientometric research of the knowledge management discipline: a 2021 update. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25(8), 1889-1925. ↩

- Alter, S. (2006, January). Goals and tactics on the dark side of knowledge management. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’06) (Vol. 7, pp. 144a-144a). IEEE. ↩

- CISA. (2023). Information Manipulation. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). ↩

- Boyes, B., Cummings, S., Habtemariam, F. T., & Kemboi, G. (2023). ‘We have a dream’: proposing decolonization of knowledge as a sixth generation of knowledge management for sustainable development. Knowledge Management for Development Journal, 17(1/2), 17-41. ↩

- Eve, M. P., & Gray, J. (Eds.) (2020). Reassembling scholarly communications: Histories, infrastructures, and global politics of Open Access. MIT Press. ↩

Bruce:

This is a necessary and extremely useful piece on the academic “state” of KM. I appreciate your compiling it.

I found your commentaries to be equally as useful as the main article!

Big win and a link i’ve bookmarked for regular reference!