Indigenous knowledge offers solutions, but its use must be based on meaningful collaboration with Indigenous communities

Tara McAllister, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington; Cate Macinnis-Ng, University of Auckland, and Dan C H Hikuroa, University of Auckland

As global environmental challenges grow, people and societies are increasingly looking to Indigenous knowledge for solutions.

Indigenous knowledge is particularly appealing for addressing climate change because it includes long histories and guidance on how to live with, and as part of, nature. It is also based on a holistic understanding of interactions between living and non-living aspects of the environment.

However, without meaningful collaborations with Indigenous communities, the use of Indigenous knowledge can be tokenistic, extractive and harmful.

Our newly published work explores the concept of kaitiakitanga. This is often translated as guardianship, stewardship or the “principle and practices of inter-generational sustainability”.

We want to encourage Western-trained scientists to work in partnership with Māori and meaningfully acknowledge Māori values and knowledge in their work in conservation and resource management.

Kaitiakitanga is more than guardianship

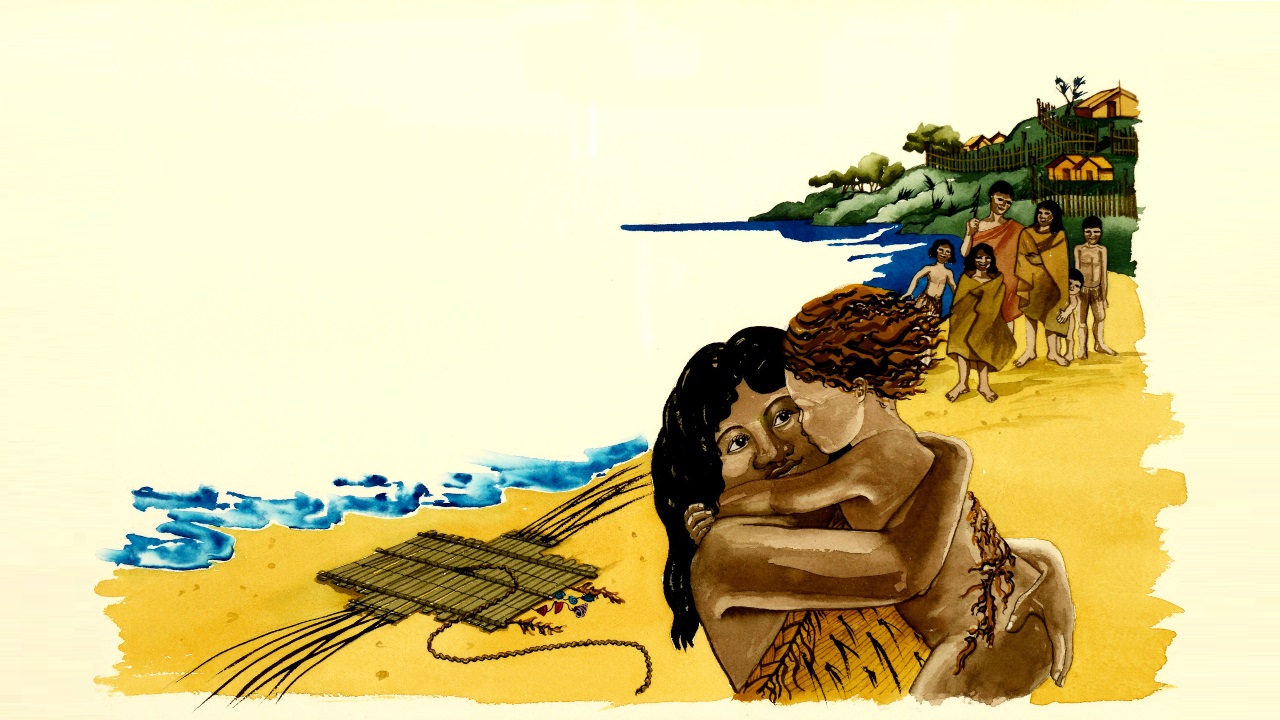

Indigenous knowledge includes innovations, observations, and oral and written histories that have been developed by Indigenous peoples across the world for millennia.

This knowledge is living, dynamic and evolving. In Aotearoa New Zealand, mātauranga Māori is the distinct knowledge developed by Māori. It includes culture, values and world view.

The concept of kaitiakitanga is often (mis)used in the context of conservation and resource management in Aotearoa. In our work, we highlight how kaitiakitanga is inherently linked to other concepts. It is difficult to translate these concepts directly but they include tikanga (Māori customs), whakapapa (genealogy), rangatiratanga (sovereignty) and much more.

One of the key conceptual differences between kaitiakitanga and conservation is that for kaitiakitanga, we consider being part of te taiao (the environment) and manage our relationships accordingly. Conservation is characterised by humans managing the environment as if they were separate from it.

The Honourable Justice Joe Williams describes kaitiakitanga as “the obligation to care for one’s own”, indicating the intrinsic link between people and the environment.

We caution against simplistic definitions of kaitiakitanga. They often divorce it from its cultural context. Simplistic definitions reduce the richness of the concept and also fail to recognise the differences in how kaitiakitanga is conceptualised and practised.

Instead, we encourage Western-trained researchers to gain a deeper understanding of concepts that underpin kaitiakitanga and work with mana whenua to further develop understanding.

Kaitiakitanga and conservation in practice

There is a growing number of examples of successful collaborations between mana whenua and researchers. Exploring these projects will allow researchers to gain insights into how to contribute in an effective and respectful way.

For instance, a study of the traditional harvest and management of sooty shearwater in the Marlborough Sounds shows the importance of including cultural harvest in species conservation management.

Similarly, putting Indigenous knowledge at the centre of the translocation of rare species improves conservation outcomes.

Rāhui in conservation

Rāhui is a customary process that can be used by mana whenua to restrict access to a certain resource or area of land to allow recovery. It includes an holistic understanding of the environmental problem, and social and political control.

Rāhui has been used to reduce the spread of kauri dieback disease in the Waitakere Ranges. It has also been used to protect kaimoana (including scallops, mussels, crayfish and pāua) on Waiheke Island.

Other examples include rāhui covering forests, lakes, beaches and marine areas for durations from days to decades. Rāhui are widely used but highly specific to local conditions. For iwi to be able to implement rāhui, they need to have rangatiratanga, as kaitiakitanga is both an affirmation and manifestation of rangatiratanga.

An effective way forward

Empowering Māori researchers and communities is central to worthwhile collaborations. We encourage non-Māori researchers to approach partnership with an awareness of the limits of their training and knowledge.

Embracing a mindset of intellectual humility will more likely create conditions for meaningful co-created work. While establishing and maintaining collaborations can be time-consuming, our collective experience is that taking time to develop trust and understanding is essential for successful outcomes.

We hope our work will provide some inspiration and guidance for established practitioners and students alike.

There are a number of other examples of how mātauranga and ecology can work together. The New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research has dedicated a special issue to mātauranga Māori and how it is shaping marine conservation. Others have explored how respectful collaborations can support better teaching of science and better research outcomes.![]()

Tara McAllister, Research Fellow, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington; Cate Macinnis-Ng, Associate Professor in Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, and Dan C H Hikuroa, Senior Lecturer in Māori Studies, University of Auckland

Article source: This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Header image source: Archives New Zealand on Flickr, CC BY 2.0.