Knowledge-related justice in international development

Instead of the common focus on understanding the multitude of epistemic injustices, our newly published paper1 in the journal Sustainable Development puts forward a new perspective on knowledge-related justice which can help us in our efforts to counteract injustices in international development.

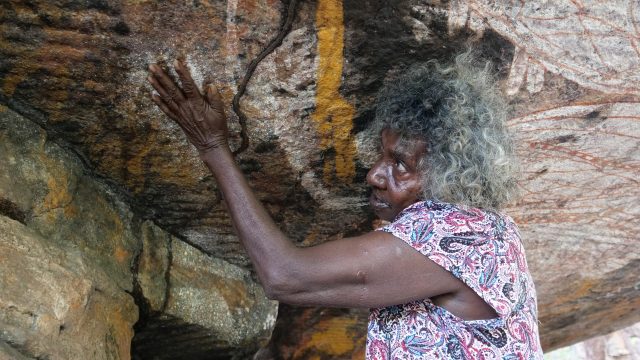

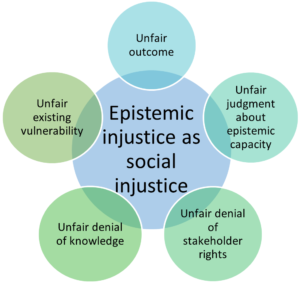

Epistemic2 means of or relating to knowledge or knowing. Epistemic injustice comprises unfair treatment related to knowledge in which the voices, experiences and problems of marginalized individuals, communities and societies are not listened to and not believed, often because of intersectional prejudices towards their gender, race, sexuality, nationality or ability. Intersectional prejudices3 refers to the ways in which different aspects of a person’s identity can expose them to overlapping forms of discrimination and marginalization (Figure 1). Skin colour, gender, nationality, disability, and sexual orientation interact, contributing to unequal outcomes in ways that cannot be attributed to one dimension alone.

Epistemic injustice can cause existential suffering, leading to imprisonment when the testimony of a defendant is not believed or, ultimately, even to death when a patient’s description of their symptoms is not taken seriously. As writer and journalist Rebecca Solnit contends4: ‘If our voices are essential aspects of our humanity, to be rendered voiceless is to be dehumanised or excluded from one’s humanity.’ You can see an introduction to epistemic justice in the YouTube video by Attic Philosophy.

The philosophical concept of epistemic injustice has received considerable attention since it was first introduced by Miranda Fricker in her 2007 book Epistemic Injustice5, but actions to reduce epistemic injustice are still in their infancy. Epistemic injustice is increasingly being employed to delineate individual and collective injustice in healthcare, information sciences, education and international development.

Embedded in many other forms of social injustice and inequality, epistemic injustice is a particularly serious problem for international development because of the way in which local knowledges and local stakeholders are often marginalized, undermining the global community’s ability to deal with ‘wicked’ problems, such as climate change.

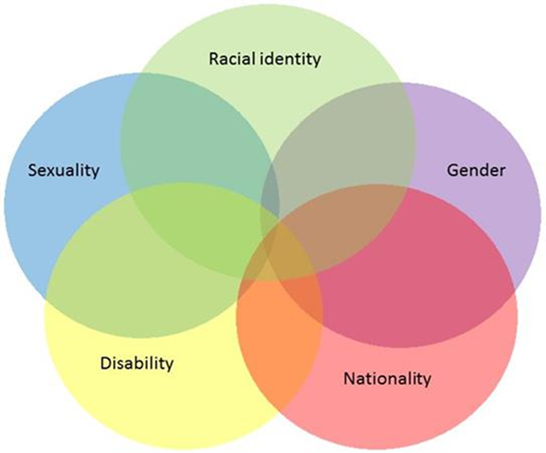

Building on the more conceptually developed, philosophical framework of epistemic injustice and recent research from other fields, our paper develops a holistic action-oriented framework of epistemic justice, namely fair treatment in knowledge-related and communicative practices, for international development and beyond. It also adds to the current framework of individual and collective injustice by including a range of new insights on structural and systemic epistemic injustice, such as linguistic injustice and epistemicide (death of knowledge systems).

Articles6 by Beth Patin and colleagues applying the concept of epistemic injustice to the information professions were particularly important in our efforts to apply the concept in international development.

In our paper, we have developed a new action-oriented framework of epistemic justice (Figure 2) with the idea that a positive focus is more likely to support change for the better, rather than only focusing on what is wrong. This new framework aims to provide an organizing structure with anchor points and signposts which can support development actors—and particularly development organizations, their staff and consultants—in their efforts to develop more just knowledge practices and to identify and preserve existing just practices. These signposts include network justice and the decolonization of knowledge but also valuing indigenous knowledge.

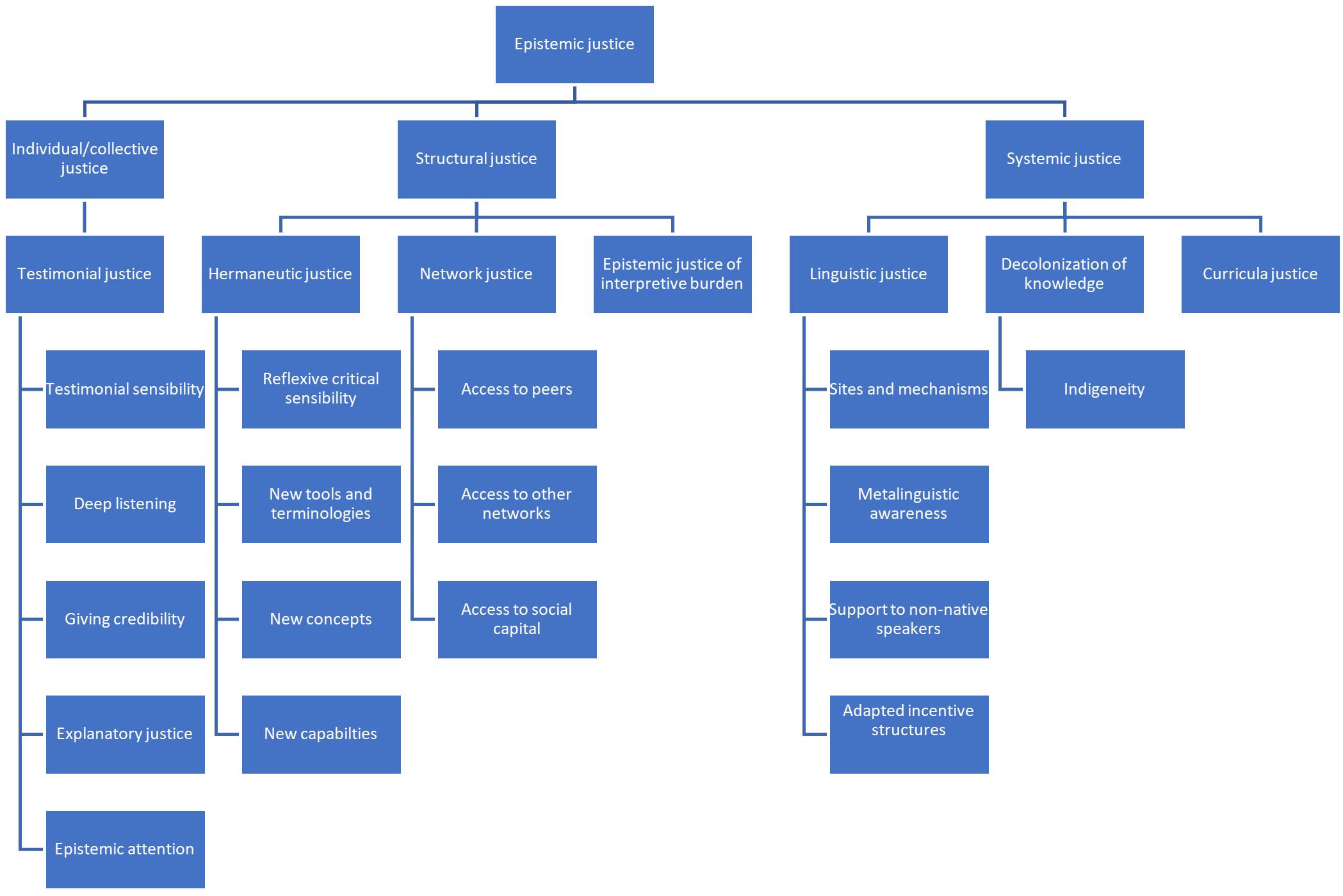

In our paper, we also stress the link between epistemic justice and social justice, arguing that there can be no social justice without epistemic justice. We employed Morten Fibieger Byskov’s recent framework of epistemic injustice7 as social injustice (Figure 3) to clearly show that epistemic injustice is a form of social injustice with particular relevance to international development. The marginalization of local people in development is often based on unfair judgement of epistemic capacity, unfair denial of their rights as stakeholders and unfair denial of their knowledge, based on an unfair existing vulnerability and leading to an unfair outcome. These five criteria determine whether epistemic injustice can be considered to be a social injustice.

Biographies:

|

Sarah Cummings, PhD is an experienced researcher and consultant with a focus on knowledge in global development, based at the Knowledge, Technology and Innovation department of Wageningen University & Research, The Netherlands. She is a member of the Knowledge Management for Development (KM4Dev) community and Editor-in-Chief of the Knowledge Management for Development Journal. |

|

Charles Dhewa is a proactive Knowledge Management Specialist committed to exceptional practical achievements in agriculture and rural development. He is the Chief Executive Officer of Knowledge Transfer Africa (Pvt) Ltd which he founded in 2006 after realizing that agricultural value chain actors in developing countries needed a knowledge broker to keep reminding them of what they could be forgetting. Among other qualifications, he holds a Master of Philosophy (MPhil) in Information and Knowledge Management from Stellenbosch University, South Africa. He is a regular blogger with his thought leadership ideas filtering into newspapers, radio and several twitter-streams. |

|

Gladys Kemboi is a Knowledge Management Specialist with over 10 years’ experience in implementing KM strategy, shaping strategies for strengthening local, regional and global experience. She is currently Global Learning and Knowledge Management Advisor at Jhpiego, an international, non-profit health organization affiliated with The Johns Hopkins University, USA. |

|

Stacey Young, PhD is USAID’s first Agency Knowledge Management and Organizational Learning Officer, leading Agency-wide knowledge and learning approaches. She also co-chairs the Multi-Donor Learning Partnership of nine major donor organizations working to advance organizational learning and knowledge management in international development. |

Article source: Doing epistemic justice in sustainable development: Applying the philosophical concept of epistemic injustice to the real world, CC BY 4.0.

Header image source: Created from Gerd Altmann and Gordon Johnson on Pixabay, Public Domain.

References:

- Cummings, S., Dhewa, C., Kemboi, G., & Young, S. (2023). Doing epistemic justice in sustainable development: Applying the philosophical concept of epistemic injustice to the real world. Sustainable Development, 1– 13. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2497. ↩

- Merriam Webster. ↩

- State Government of Victoria. (2021, February 8). Understanding intersectionality: Definition of intersectionality and how it can lead to overlapping of discrimination and marginalisation. ↩

- Solnit, R. (2017, March 8). Silence and powerlessness go hand in hand – women’s voices must be heard. The Guardian. ↩

- Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic justice: power and the politics of knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↩

- Patin, B., Sebastian, M., Yeon, J., Bertolini, D., & Grimm, A. (2021) Interrupting Epistemicide: A Practical Framework for Naming, Identifying, and Ending Epistemic Injustice in the Information Professions. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 72(10), 1306-1318. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24479. ↩

- Byskov, M.F. (2021). What makes epistemic injustice an “injustice”? Journal of Social Philosophy, 52(1), 114–131. ↩