Knowledge-focused design thinking

Once an innovation buzzword, the concept of “design thinking” has now become a widely diffused practice. Indeed, a 2018 systematic review1 of research on design thinking reports that “prominent academic journals, including Journal of Product Innovation Management and Academy of Management Journal have identified design thinking as a critical concept in both innovation and general management.”

In this article, I explore the application of the design thinking methodology to understand and define organizational knowledge needs, select the optimal solutions, and implement them in an agile manner.

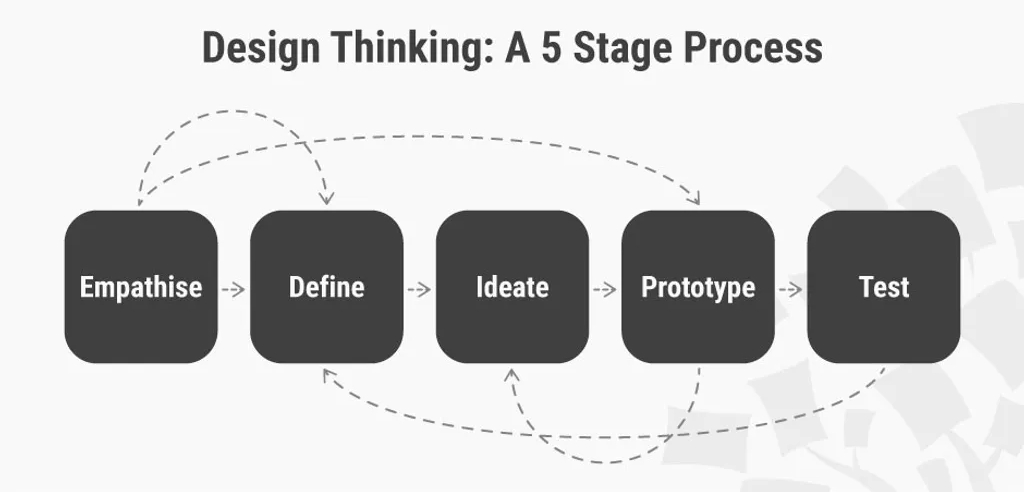

Design thinking is a human-centered process for creative problem solving that iterates between user perspective (problem space) and product specification (solution space). It can be defined2 as a process that “brings together what is desirable from a human point of view with what is technologically feasible and economically viable. It also allows people who aren’t trained as designers to use creative tools to address a vast range of challenges.”

A designer can be described3 as someone “who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.”

There are many approaches to the utilization of design thinking. The discussion here makes use of the five-phase design thinking model4 proposed by the Hasso-Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford University.

The empathy phase is a rigorous process for understanding the real needs of knowledge workers or clients about all knowledge-related aspects. It is common when asking a question regarding one’s needs to receive an answer that describes a desired specific solution, not the actual need. A well-known example is Henry Ford’s quotation7: “If I had asked people what they wanted they would have said faster horses.” The empathy stage includes three types of activities: observation, participation, and interviewing.

Observation is watching the activity from a vantage point without involvement of any type, like an anthropologist watching the behavior of an ancient tribe from a distance.

Participation is to do the same thing as the knowledge worker (or the client) to share their feelings (like walking in their shoes or entering their heads).

A knowledge worker’s schedule may include information and knowledge acquisition and curation, creation of new knowledge, implementing (using) knowledge, documentation, participation in meetings, designing, making decisions, involvement in organizational processes alone or as a team member, reading and writing emails, etc.

The knowledge-focused empathy phase should consider the various aspects of the knowledge-related work of typical knowledge workers (preferably grouped under personas):

- what information and knowledge do they need to perform well

- locations and methods to acquire external or internal information and knowledge

- bottlenecks and difficulties in the information flows

- the types of knowledge they need and cannot get

- experts relevant for help in resolving problems, their availability and their contact information

- participation in a community (or communities) of practice at work

- knowledge contribution

- reuse of knowledge contributed by other workers

- knowledge organizational culture (tolerant toward mistakes, attitude toward knowledge sharing)

- existence of knowledge governance

- technological infrastructure (systems existence performance and ease of use)

- pain points

- envisioned infrastructure for better or easier functioning

- how do they consider themselves regarding knowledge – user, creator, broker

- the number of emails they receive daily and the way to deal with them, do they feel overloaded with information

- how much time they spend daily searching for information

- the use of knowledge for decision making

- the level of confidence in local information

- awareness of mechanisms for dissipating new or updated knowledge in relevant interest groups (e.g. communities of practice) and using these communities for creation of new knowledge

- etc.

The AEIOU framework9 helps in the empathy phase by providing guidance: “AEIOU is a framework which guides designers in thinking through a scenario or a problem from a variety of perspectives.”

The AEIOU framework includes five perspectives: activities, environments, interactions, objects, and users. Using it helps obtaining comprehensive answers in the empathy phase. These perspectives are different for various knowledge-related processes, e.g., the knowledge required for starting a project differs from the knowledge required to evaluate the status of a project. Organizational processes are usually different10 for company business models – asset builders, service providers, technology creators, and network orchestrators.

The empathy phase should be performed for representative users from different units or different working styles (should be listed as personas in the final report).

Observations are especially suitable for jobs that do not require a high level of proficiency such as call center workers or office receptionists. Spending a couple of hours watching them can provide insights into their operational routines and prepare questions for a deeper understanding of the types of knowledge they use and the ease of obtaining answers to problems that they do not know how to handle.

Participation in group activities such as meetings, brainstorming sessions, or design reviews is especially useful in understanding knowledge workers’ routines. Typical insights are sources of knowledge that are used (explicit/tacit), problems such as ease/difficulty of retrieving required documents during the meeting, the use of old (not up to date information), recording and distributing the minutes, etc. Participating in the work of professionals such as nurses or service engineers is not realistic.

Interviews are usually very helpful in understanding knowledge-related issues. Detailed guidance on performing interviews is given by IDEO.org11. I prefer semi-structured interviews which include open questions such as ‘what is the most disturbing problem in accessing knowledge?’, or ‘how do you think things could be improved?’. The interviews should focus on the use of knowledge in work processes. Sample questions:

- What knowledge do you rely on when performing the activity?

- Can you access the knowledge without assistance?

- Do you know who to ask regarding knowledge that you need?

- Who should know?

- Is the knowledge up to date?

- Bottlenecks in knowledge flow.

- Points that require improvement.

- Where is knowledge created in the process?

- Where is it stored? a central location? Private?

- How is it organized?

- To whom is the created knowledge accessible?

Accumulating all the acquired information and making sense of it constitutes the “define” phase.

Einstein advises12 to devote the main effort to the most important part in the process – the first two phases: “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

The remaining three phases will be then performed, including updating the “define” phase (design thinking is a non-linear process). The ideate phase can make use of many tips for KM solutions13 that offer a great user experience.

Finally, the results should comply with the three basic requirements14:

- Technically feasible: They can be developed into functional products or processes.

- Economically viable: The business can afford to implement them.

- Desirable for the user: They meet a real human need.

Emphasis points

Needs vs. requirements (or demands)

It happens quite often that a knowledge worker/client saw a system such as SharePoint, in another organization, and requests its implementation being sure that it will solve all the problems. However, professional examination of the real needs may reveal that another system is more appropriate for the specific need. Identification of the real needs allows therefore to choose the most appropriate solution from those available on the market and not be limited to a single solution determined by the user or client.

The advantage of co-creation

Design thinking is a human-centered process15. The basics of this are:

- Thinking about what people want to do rather than what the technology can do.

- Designing new ways to connect people with people.

- Involving people in the design process.

- Designing for diversity.

Working together with the users/clients and getting them to be involved in all the design thinking phases results in the distillation of the real needs through the lens of ease, convenience, and efficiency in performing their tasks so they can do their work, easier, faster and to provide better results. Mutual agreement on the needs and the solution makes users feel that they are legitimate participants because they took part in devising the solution and it was not imposed on them. This feeling is important especially when the implementation results in new work routines. In other words – it assists change management.

Knowledge and knowledge management – the foundation for ideation

Einstein contended that16: “The only source of knowledge is experience.” The various ideas on how to respond to the needs that have been defined, are based on previous experiences and knowledge. The way similar problems were solved in other organizations, the relative performance of competitive solutions, the service level, the possible effect of the organizational culture concerning KM on the suggested solution, etc.

Iteration

Design thinking is an agile, non-linear process. This philosophy translates into successive iterations among the five phases until consensus is achieved. Once a solution is decided upon in the ideate phase a prototype should be built and tested. The testing can be performed in a small unit e.g., a part of the R&D department, or by a small group of vigilant knowledge champions. The testers’ bad experiences are translated into prototype fixes that are then re-tested until good user experience is achieved.

Having accomplished these steps is helpful in the successful implementation of a knowledge management initiative.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Balaji Iyer, Rudolf D’Souza, Bruce Boyes and Yair Dembinski for helpful suggestions that greatly improved the article.

Header image source: Arek Socha on Pixabay.

References:

- Micheli, P., Wilner, S. J., Bhatti, S. H., Mura, M., & Beverland, M. B. (2019). Doing design thinking: Conceptual review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 36(2), 124-148. ↩

- Brown, T. (n.d.). Design Thinking Defined. ↩

- Simon, H.A. (1996). The Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd Edition, p. 111, MIT Press, ISBN: 978026219051. ↩

- Stevens, E. (2021, November 23). What Is Design Thinking? A Comprehensive Beginner’s Guide. Career Foundry. ↩

- Dam, R.F. (2021). 5 Stages in the Design Thinking Process. ↩

- Stevens, E. (2021, August 5). What Is Empathy in Design Thinking? A Comprehensive Guide. Career Foundry. ↩

- Unicornsulting. (n.d.). Henry Ford and Empathy. ↩

- Fletcher, K. (2017, June 13). Bronislaw Malinowski – LSE pioneer of social anthropology. LSE History. ↩

- Pandey B.K. (2021, May 29). AEIOU of Design Thinking. LinkedIn Pulse. ↩

- Collins, R. (2019, January 22). The Digital Transformation of the Firm. LinkedIn Pulse. ↩

- IDEO.org. (2015). The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design. ↩

- Einstein, A. (n.d.). Goodreads Quotable Quotes. ↩

- Garfield, S. (2017). Proven Practices for Promoting a Knowledge Management Program, p. 93. Lucidea Press, ISBN 978-1-7750631-0-0. ↩

- Stevens, E. (2020, January 30). What is design thinking, and how do we apply it? Inside Design. ↩

- Benyon, D. (2019). Designing User Experience, Fourth Edition, p.23. Pearson Education Limited, UK, ISBN 9781292155517. ↩

- Einstein, A. (n.d.). Goodreads Quotable Quotes. ↩