Co-creative approaches to knowledge production and implementation series (part 7): Critical success factors for building trust and sharing power for co-creation in Aboriginal health research

This article is part 7 of a series of articles based on a special issue of the journal Evidence & Policy.

In the third of the papers in the research section of the special issue, Sherriff and colleagues1 describe the critical success factors behind the Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH), focusing on how SEARCH was established, and continues to build trusting co-creative relationships. They also explore some continuing challenges and consider how the SEARCH partnership might be strengthened.

Sherriff and colleagues advise that historically, Aboriginal health research in Australia has been non-participatory, misrepresentative, and has produced few measurable improvements to community health. Recognising this, SEARCH was established to co-create and co-translate research. Over the past decade, SEARCH has built a sustainable partnership across policy, research, clinical and Aboriginal community sectors which has resulted in improvements in Aboriginal health through enhanced services, policies and programmes.

The study illustrates how SEARCH, a co-creative partnership between Aboriginal services, researchers, policymakers, and clinicians, has built trusting relationships that have led to tangible outcomes for Aboriginal communities. It is a ‘real world’ case example of a sustained and productive partnership in Aboriginal health demonstrates how co-creation principles can be operationalised through ethically-informed structures and processes.

The history of research in Aboriginal health

To illustrate why Aboriginal health research should be co-created with Aboriginal communities, Sherriff and colleagues begin their paper by charting the disturbing history of Aboriginal health research in Australia.

Historically, research involving Australian Aboriginal people has been problematic and has often been exploitative and invasive, consistently failing to recognise the diversity of Aboriginal cultures, values, kinship and spirituality. Moreover, it has failed to acknowledge the profound trauma of massacres, forced removal of children, dislocation from traditional lands and the ongoing impact of post-colonial experiences. As a result Aboriginal communities have been misrepresented in research findings and researchers have ridden roughshod over communities, cultures, practices and beliefs. Similar experiences have been observed globally in research with other Indigenous groups.

In recent years, there has been superficial compliance with ethical guidelines, and most reviews in Aboriginal health have had poor methodology and been conducted by non-Aboriginal researchers. Much research has reinforced a deficit view of Indigenous people, and many so-called evidence-based policies and programmes have been experienced as paternalistic and punitive. Further, research has primarily targeted rural and remote populations, despite more Aboriginal people living in urban and regional areas. Culturally inappropriate data collection and de-contextualised interpretation have not produced meaningful findings and Aboriginal communities report receiving few benefits, despite being one of the most researched populations in the world. In fact, Aboriginal people continue to experience much poorer health and wellbeing than the general Australian population as reflected by lower life expectancy, education and employment rates, and higher rates of hospitalisation, homelessness, family violence and incarceration.

Given this history there is, understandably, an often deep distrust by Aboriginal people towards research purporting to be for the good of their communities.

The need for co-creation

The tide is now turning, with Sherriff and colleagues reporting that it is now accepted that Aboriginal health research should be co-created with Aboriginal communities.

Co-creation is a primary mechanism for producing meaningful research for health policy and practice. Co-creation can facilitate critical thinking and cross-sector communication, integrate diverse forms of knowledge, generate local ownership of programmes, and harness frontline expertise in implementing and evaluating programmes in complex health systems.

Co-creation builds on participatory research methods that recognise power imbalances brought about by social inequities and use strength-based empowerment approaches to address community needs. These models aim to treat service users as active agents rather than recipients, and establish equal relationships where diverse forms of knowledge and experience are valued and used synergistically to produce practical outcomes. Such participative approaches are especially appropriate when working with Aboriginal people and other Indigenous groups as they address power imbalances and privilege forms of knowledge not typically acknowledged in research.

SEARCH and its achievements

The Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH) is a cohort study of 1669 Aboriginal children and their caregivers from urban and large regional areas of New South Wales (NSW), designed to address community-identified priorities, enable the informed and ethical engagement of community members in research processes, and facilitate the translation of culturally relevant research findings into improved health outcomes.

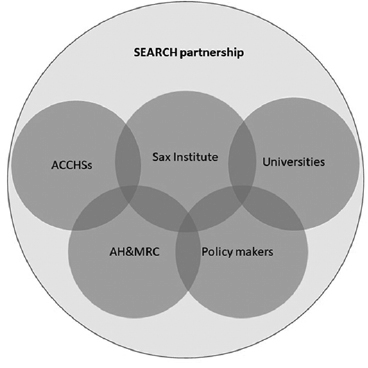

As shown in Figure 1, SEARCH is underpinned by a cross-sector research partnership which was established in 2008. ACCHSs: Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services; AH&MRC: Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Centre; Universities: University of Sydney, The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network, Australian National University, University of Melbourne, Flinders University, University of Wollongong; Policymakers: NSW Ministry of Health, NSW Family and Community Services, NSW Health Local Health Districts, NSW Department of Education.

Sherriff and colleagues report that, to date, SEARCH has successfully contributed to enhanced children’s access to specialist clinical services such as the Hearing, Ear Health and Language Services (HEALS) programme through which 1047 Aboriginal children have received care, including 7830 occasions of speech and language pathology services and 314 Ear Nose and Throat (ENT) surgeries . Findings from SEARCH have been used to redesign Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service (ACCHS) services, and new models of mental healthcare for Aboriginal children and adolescents are being introduced in some health districts. SEARCH’s high-quality data has been used to advocate for further funding for research and services; for example, it was used in a grant which resulted in $1 million for smoking cessation programmes and was instrumental in attracting funds for a speech pathologist at two ACCHSs. The dissemination of SEARCH findings has fostered the creation of closer working relationships between mainstream and Aboriginal services which, in turn, has strengthened pathways to services.

Critical success factors

To identify the critical success factors behind SEARCH, Sherriff and colleagues conducted semi-structured interviews with 26 stakeholders who were selected to obtain maximum diversity of roles and perspectives. Interview questions explored concepts that informed the development of SEARCH such as trust, transparency, leadership, governance, reciprocity and empowerment. Interviews lasted an average of 35 minutes. A large proportion of the participants were female, which broadly reflects the sex distribution of stakeholders involved in SEARCH.

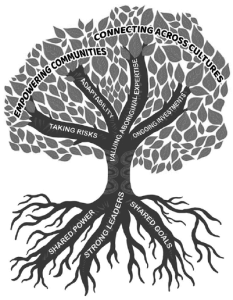

Nine critical success factors for trusting co-creation partnerships in SEARCH were identified: shared power; strong credible leadership; shared vision and goals; willingness to take risks; connecting across cultures; empowering the community; valuing local Aboriginal knowledge; ongoing investment and collaboration; and adaptability.

Figure 2 shows how these concepts relate to each other. Shared power, strong credible leadership, and shared vision and goals provide the foundation for trusting relationships. A willingness to take risks, ongoing investment and collaboration, valuing local Aboriginal expertise, and adaptability of the model ensure it is meaningful and sustainable. The reward is mutual learning achieved through connecting across cultures, and empowerment of Aboriginal communities through building capacity and improving health services.

Shared power

- Balancing control. Collective control, enshrined in SEARCH’s strong governance arrangements, was viewed as integral to co-production.

- Shared responsibilities. Governance in SEARCH is designed to facilitate the involvement of ACCHSs in decision making and data collection without overburdening them.

Strong credible leadership

- Diverse expertise. Interviewees regarded SEARCH as successful in building and maintaining productive partnerships and identified the involvement of Aboriginal people in senior leadership roles (including chief and associate investigators) as a key factor. Moreover, policy interviewees felt the involvement of the Sax Institute, an organisation that works at the interface of research and policy, was integral to SEARCH’s successful engagement with government.

- Distributed leadership. Interviewees regarded SEARCH’s leadership as “shared but not uniform”, with people leading different areas of work, and coming together regularly for reporting and decision making. This ensures everyone has a voice and diversifies the partnership’s perspective.

Shared vision and goals

- A values-based foundation. SEARCH was founded by a coalition whose goals were to facilitate equal partnerships with ACCHSs and work long-term towards empowering Aboriginal communities to control research that affects them.

- Making a difference. All the partners within SEARCH aim to drive real change in Aboriginal health.

- Seeing it through. This shared commitment to effecting change has withstood many challenges.

Willingness to take risks

- A leap of faith. Given the history of Aboriginal research in Australia, and the deep distrust of research, SEARCH represents a considerable, ongoing risk for all involved. Therefore, the involvement of every single participant in SEARCH represents a significant leap of faith. Many of SEARCH’s initial and ongoing strategies have been developed with this risk in mind. These include acknowledging the history, formally agreed protections, honouring trust, transparency, and delivering outcomes.

- Risks for researchers. Initially, SEARCH posed professional risks for investigators who were committing to a long-term unfunded project in which tangible outcomes were distant. However, these shared risks were instrumental in forming bonds that have helped to sustain the partnership.

Connecting across cultures

- Relationship building. Aboriginal interviewees indicated that both the quality and quantity of interaction was important for building and sustaining trusting relationships. Small, frequent and informal meetings are key, and other facilitators are frequent telephone contact between partners at all levels, formal events including an annual forum and community events, and when Coordinating Centre staff assist ACCHSs with data collection and engage directly with the community. However, both policymakers and researchers felt that engagement across their domains could be increased.

- Mutual learning. An essential component and benefit of co-creation was mutual learning. The Aboriginal community learns about research, while ACCHSs and Coordinating Centre staff educate researchers on cultural competence. Over time, understanding between partners has been facilitated by cross-sector mobility: SEARCH researchers have moved into policy positions, and ACCHS staff have moved to the Coordinating Centre.

- Understanding motivation. Aboriginal interviewees felt researchers had taken the time to understand what motivated communities and so were better able to engage with them meaningfully. Understanding motivation leads to meaningful participation.

Empowering the community

- Equipping communities for action. Interviewees felt that communities often already know what needs to change in their communities but lack the resources to carry out programmes or advocate for services. SEARCH research and evaluation data has equipped participating communities to critique and revise their current programmes, develop new programmes, make persuasive cases for additional funding, and advocate more effectively for policies that impact on community health and wellbeing.

- Building research capabilities. SEARCH supports ACCHS staff to gain skills in collecting, managing, interpreting and using data for service design and improvement, and to undertake formal higher education.

- Demystifying research. SEARCH’s communication strategy has been strongly informed by the information preferences of ACCHS staff and community members.

- Saying ‘No’. Interviewees felt SEARCH had given ACCHSs the confidence and knowledge to critically assess research, empowering them to decline involvement in other research projects that were not participatory, and call out SEARCH researchers who might try to dominate proceedings or embark on research of purely academic or individual interest.

Valuing local Aboriginal knowledge

- Equity and respect. Interviewees repeatedly commented that everyone involved in SEARCH is treated as an equal with valuable knowledge to contribute.

- Local interpretation. Interviewees noted that the SEARCH model of employing local Aboriginal staff to provide guidance throughout the research design, conduct, analyses and translation was unique. Local Aboriginal interpretation of results ensures data are interpreted in context and is critical to maintaining trust.

Ongoing collaboration and investment

- An ongoing commitment. When SEARCH was established the community wanted a long-term study rather than the fragmented approach to research and programmes common in Aboriginal health.

- Resourcing and reciprocity. Interviewees argued that the project was sustainable partly because SEARCH employs an Aboriginal workforce within the services to engage with families and collect data, and resources this position, rather than adding to the heavy workload of ACCHSs. Staff turnover was seen as a significant threat to SEARCH’s sustainability as knowledge and relationships could be lost.

- Following through. Interviewees felt SEARCH was unique in keeping community partners involved with all projects. This included having a dedicated Aboriginal knowledge broker working to articulate emergent findings, support collaborative interpretation and, importantly, to co-create policy and practice solutions.

Adaptability

- Emergent project design. SEARCH has an emergent design that is responsive to community needs.

- Local adaptation. As the core business of ACCHSs is providing healthcare and they are often overburdened due to poor resourcing, it has been essential to accommodate each ACCHS’s requirements. SEARCH has adapted to diverse priorities, infrastructures and preferences for participation and research translation. Adaptations have also been made in response to the evolution of trust and familiarity within SEARCH. Consequently, SEARCH’s governance has a firm core structure but supports local modification.

Challenges for ongoing co-creation in SEARCH

As part or their study, Sherriff and colleagues have identified some areas for ongoing improvement to ensure that SEARCH is sustainable and improving Aboriginal health outcomes.

These include continuing development of Aboriginal research capacity, greater sensitivity and frequency in communications, more contact between non-Aboriginal researchers and Aboriginal communities, and methods for embedding shared ownership of the programme’s ethos and activities.

The partnership has withstood considerable changes to resources, networks and infrastructure, and has survived misunderstandings, funding droughts and the flux associated with health service ‘reforms’. The strong reciprocal relationships between partners at multiple levels appears to have created a resilient platform that is not dependent on any one person or process. However, if experienced at a larger scale, or in combination, future challenges could prove insurmountable. The difficulty in appropriately resourcing projects in Aboriginal health in an ongoing challenge. Continuous work must be done to ensure that current partners are engaged with and committed to the programme’s ethos and activities, that established relationships are nurtured, and that strategic relationships with new, values-driven partners are actively forged.

While decision making in SEARCH aims to be highly inclusive, and the strong governance structure provides a solid structure for the partnership, it cannot eradicate power differentials in day-to-day operations. Organisational and disciplinary hierarchies can make it hard for junior partners, and some ACCHS staff, to have a voice in meetings where the onus on research can privilege those with technical knowledge, and which, due to the dispersed locations of partners, are usually held by teleconference. Most forums focus on senior members of the partnership and this can leave important partners, such as ACCHS research officers (who function as frontline leaders of SEARCH within the community) out of the loop. SEARCH still has work to do in ensuring that decision making accommodates ‘bottom-up’ ideas and critiques. Holding more meetings locally at ACCHS sites, and chairing by Aboriginal partners, might help. Additionally, researchers occasionally default to conventional research strategies, use jargon and fail to ensure that community members have real opportunities to contribute. All partners need to remain vigilant to this slippage, with senior researchers taking responsibility for modelling and correcting practices.

There is more work to do in developing community ownership of SEARCH. For example, building research capacity in the ACCHSs has been moderately successful, but more Aboriginal people could be supported to complete higher education degrees and work as researchers on SEARCH projects.

As SEARCH has matured, structures and processes have been adapted, but the partnership is probably not as reflexive as it could be. Greater focus on reviewing structures and processes, in relation to current needs and goals, might enhance the partnership’s functioning and effectiveness.

Next part (part 8): A research protocol for studying the relationship between technical assistance, evidence use, and stakeholder participation.

Article source: Adapted from the paper Building trust and sharing power for co-creation in Aboriginal health research: a stakeholder interview study published in the Evidence & Policy special issue Co-creative approaches to knowledge production: what next for bridging the research to practice gap?, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Acknowledgements: This series has been made possible by the publication of the special issue as open access and under a Creative Commons license. The guest editors and paper authors are commended for their leadership in this regard.

Header image source: Adapted from an image by Michelle Pacansky-Brock on Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

References:

- Sherriff, S. L., Miller, H., Tong, A., Williamson, A., Muthayya, S., Redman, S., … & Haynes, A. (2019). Building trust and sharing power for co-creation in Aboriginal health research: a stakeholder interview study. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 15(3), 371-392. ↩

Also published on Medium.