Case studies in complexity (part 5): Queensland land clearing campaign

This article is part 5 of a series featuring case studies in complexity from the work of RealKM Magazine’s Bruce Boyes.

Background

- Land clearing in Queensland, Australia. The Australian state of Queensland has had one of the world’s highest land clearing rates, with devastating impacts on the natural environment. The land clearing has occurred on privately owned and leased land, with much of the clearing being carried out to create farmland to be used for either grazing or cropping.

- Environmental group land clearing campaign. Through the 1990s, environmental non-government organisations (ENGOs) increasingly pushed for the introduction of laws to control the high rates of land clearing in Queensland. Between 2000 and 2004, a coordinated campaign was waged by The Wilderness Society (TWS), Queensland Conservation Council (QCC), World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF) and Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF).

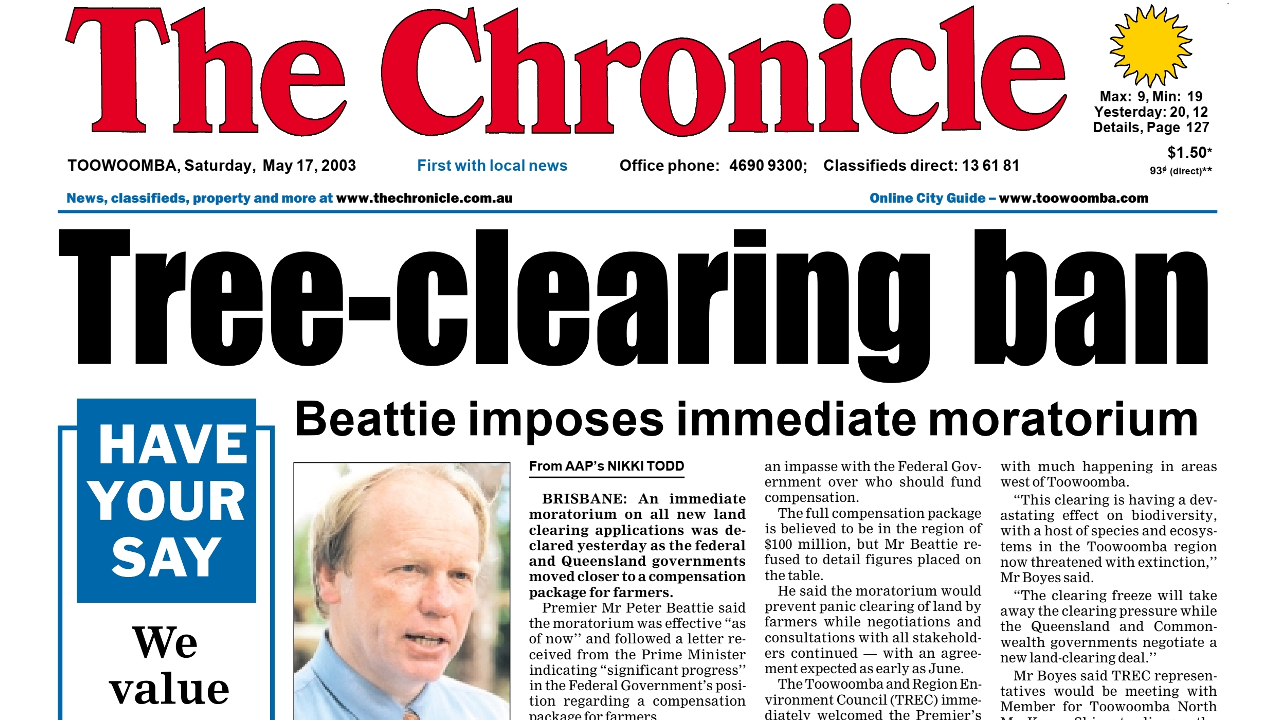

- Moratorium and policy development. Fears in rural communities in regard to the potential impact of land clearing controls triggered panic clearing which accelerated the already high land clearing rate. In May 2003, the then Labor Party Queensland Government introduced a moratorium on all land clearing to stop the panic clearing while policies to control the clearing were developed. After the moratorium was put in place, the government announced a consultation process involving committees at both state and regional level. The committees were made up of a diverse range of relevant stakeholders including farmers and conservationists. Strict land clearing controls were subsequently introduced.

Why it’s complex

- Diverse and divergent perspectives. The land clearing created a situation of conflict between primary production objectives on one hand and conservation objectives on the other. There are a diverse and divergent range of associated perspectives across society, government, and the research community in regard to where the balance between farming and conservation lies, and how to achieve that balance.

Approach

- Analysis of campaign. The approach taken in the ENGO land clearing campaign and its outcomes are analysed in the 2004 paper “Rethinking deliberative governance: dissecting the Queensland landclearing campaign” 1. The paper discusses how conservationists initially engaged with the deliberative democracy processes established by the Queensland Government, but chose to abandon these processes and instead mount a coordinated major campaign. The paper concludes that:

The landclearing campaign victory in early 2004 represents a significant turning point in land use management in Queensland. The culmination of campaigning by the conservation movement over at least the last decade will halt all landclearing by 2006, effectively saving 20 million hectares of Queensland’s remnant vegetation. This was achieved through unified collaboration by a range of ENGOs, forming an “unbeatable” campaign that engaged in a strategic range of grassroots community mobilisation, rallies, protest, science and technical research, lobbying and electoral politics.

The remarkable campaign that led to this environmental commitment highlights an apparent rupture between the discourses and practices of deliberative governance and adversarial power politics. The orthodox processes of consensus politics were rejected as inadequate by conservationists in favour of a strategic blend of community mobilisation, electoral politics and protest. Environment movement leaders considered the deliberative processes available through government-initiated stakeholder consultation entirely inadequate to deliver required conservation outcomes and sought, instead, to hold government accountable for both setting and enforcing rigorous conservation standards. This approach was at odds with the prevailing emphasis on decentralised and collaborative forms of environmental democracy, and at odds with many of their allies in the conservation movement who opted to participate in government-initiated processes.

Outcomes

- Weakening of clearing controls. The campaign outcome of a halt to all landclearing by 2006 was short lived. While farmers received compensation for having land clearing on their land restricted, their perspectives hadn’t been adequately considered and addressed in the development of the land clearing controls. As a result, opposition against the controls progressively grew, and a 2012 change of Queensland government from the Labor Party to the rural-oriented Liberal National Party saw legislation passed in 2013 that greatly weakened the controls.

- Land clearing rates again skyrocketed. From 2013, land clearing rates again skyrocketed, with Queensland back in the headlines for again having one of the world’s worst land clearing rates. The political orientation of the Queensland Government has since changed again, from the Liberal National Party to the Labor Party. The Labor Party attempted to reintroduce strong land clearing controls in 2016, but was defeated in parliament. The Labor Party then succeeded in introducing new landclearing controls in 2018, but was criticised for still failing to adequately consider the perspectives and needs of rural landholders.

- Political football. Any future change of Queensland Government from the Labor Party to the Liberal National Party is likely to see the land clearing controls again weakened, with yet another corresponding dramatic rise in land clearing rates.

Lessons

- Outcome bias. The 2004 paper “Rethinking deliberative governance: dissecting the Queensland landclearing campaign” was prepared from in-depth interviews with activists who were central to the land clearing campaign. In the wake of their significant campaign success, these activists were quick to judge their campaign approach an outstanding success. However, time has shown the activist campaign to actually have been a failure. The campaign was also not as unified as implied in the paper (see “My involvement in this case study” below).

Dr Matthew Welsh2, a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Adelaide, alerts to the phenomenon of outcome bias in a comment on the i2insights blog. He advises that outcome bias3 is the tendency to judge the quality of a decision by its outcome rather than by the quality of the decision process used. If there is a good outcome, people can assume that the decision was right even it it wasn’t the best possible decision at the time it was made (and vice versa for bad outcomes).

Indeed, in claiming that their approach was right, the activists overlooked clear indications that the successful campaign might be short lived due to a change in government, with this having already happened in 1996. The 2004 paper “Rethinking deliberative governance: dissecting the Queensland landclearing campaign” states that: “An early victory for the campaign resulted in the development of a draft set of guidelines for management of leasehold land by the Goss Labor Government in 1995 (these were subsequently rescinded by the state National Party in 1996).”

- Hindsight bias. The 2004 paper “Rethinking deliberative governance: dissecting the Queensland landclearing campaign” describes an “unbeatable” campaign, suggesting that the conservation activists believed that they always knew that their campaign would achieve success. However, in holding this belief they have overlooked other potential causal factors. One such factor was the negative misinformation campaign waged by key rural lobby group AgForce, which did not have the support of many farmers (see “My involvement in this case study” below). The Labor Party Queensland Government was also alienated by AgForce’s tactics. For example, an AgForce leader chose to not turn up to an arranged meeting with Queensland Premier Peter Beattie, a deliberate snub that understandably left the Premier distinctly unimpressed. A much more positive AgForce campaign may have gained a larger groundswell of rural community support and also positively influenced the Queensland Government, rivaling or even toppling the conservation campaign.

In his i2insights blog comment, Dr Matthew Welsh also alerts to the compounding phenomenon of hindsight bias4. Once an event has occurred, it becomes clearer which of the starting conditions and potential causes were actually relevant and which were not. That is, we can create a causal explanation for why a particular event occurred. Having this explanation, it makes sense – given our limited cognitive abilities and the goal of gaining true knowledge of the world – for us to forget the other, possible causal explanations that turned out not to be true.

My involvement in this case study

I worked on the Queensland land clearing campaign as Coordinator of Toowoomba and Region Environment Council (TREC) in 2003. TREC is one of the member regional conservation councils of the Queensland Conservation Council (QCC). Previously, in 1995-96, I had been a member of the executive of QCC and also chair of the QCC Sustainable Energy Working Group.

Although the regional conservation councils were part of QCC, very little information on the land clearing campaign had come to TREC from QCC, and my awareness of the issues was coming from being a member of one of the Regional Vegetation Management Plan (RVMP) working groups and also TREC media monitoring. The RVMPs were a key part of the Queensland Government’s land clearing policy consultation process.

A government process-weary TREC had already moved from participation to advocacy against Toowoomba City Council in regard to urban land clearing, and through both the media and my RVMP working group involvement I started to get a very strong feeling that I was participating in a predetermined process. I was also increasingly concerned about the land clearing misinformation that rural industry lobby group AgForce was promulgating, which I firmly believe was a key contributor to the panic clearing that occurred at that time.

So, with the consent of the TREC management committee I commenced public advocacy. This campaigning gained good media coverage and included direct criticism of AgForce. At the time I received numerous phone calls from pro-environment farmers west of Toowoomba who were either AgForce members who felt AgForce wasn’t appropriately representing member views, or non-AgForce members who felt that AgForce wasn’t appropriately representing overall rural community views. This highlights the complexity of the issue.

I also received an anxious call from the conservation campaign group discussed in the 2004 paper “Rethinking deliberative governance: dissecting the Queensland landclearing campaign” expressing concern that I was directly attacking AgForce. This was the first contact that TREC had received from the campaign group despite TREC having much of the land clearing activity within its geographic area of interest. I disagreed with their viewpoint, saying that I believed the misinformation being spread by AgForce was dangerous and destructive and needed to be challenged. However, I also understood the desirability of a unified campaign, so I agreed to join the campaign group. Collaboratively, we organised a number of very effective actions, including a visit by Keith Bradby to Toowoomba, which resulted in excellent media coverage. I also agreed to coordinate a “Green Graziers” landholder letter writing campaign using TREC’s networks and the additional contacts I had made and was making from the pro-environment farmer calls that TREC was receiving.

At a particular point the campaign group felt that it was desirable that the conservation movement representatives on all of the RVMP working groups resign, completely abandoning participation in the Queensland Government process as discussed in the 2004 paper “Rethinking deliberative governance: dissecting the Queensland landclearing campaign”. This was an easy decision for me to support as I was then directly involved in the campaign group and had also long felt that the RVMP process was a predetermined farce. However other regional conservation council and group representatives who had not been close to the campaign group disagreed and chose to remain involved. They argued that the central campaign group was adopting an all-or-nothing approach with a high risk of failure (whereas in my view the RVMP process had already failed). I consider that the lack of regional engagement by the central campaign group was a flaw in the campaign. They really only involved me because they were worried about what I was saying publicly – most other people were pretty much kept in the dark. This appeared to be a somewhat deliberate command and control approach by the campaigners involved.

Rather than providing a basis for questioning the appropriateness of deliberative democracy to conservation decision-making, I would argue that the long-term outcomes of the Queensland land clearing campaign mean that it does the opposite. The deliberative democracy processes used by the Queensland Government were seriously flawed, but they could have been improved rather than abandoned. I now regret participating in the Queensland land clearing campaign, but at the time participation was what I thought was the right decision. The aftermath of the campaign serves as a valuable lesson for me.

Header image source: Toowoomba Chronicle, 17 May 2003.

References and notes:

- Whelan, J., & Lyons, K. (2004, November). Rethinking deliberative governance: dissecting the Queensland landclearing campaign. In proceedings of Ecopolitics VX International Conference. Macquarie University, Sydney (pp. 12-14). ↩

- Dr Matthew Welsh is a psychological scientist specialising in decision making. As part of this research, he works with oil companies, helping them to identify psychological biases in personnel and processes and developing training regimes and decision support tools to limit or eliminate those biases. ↩

- Baron, J., & Hershey, J. C. (1988). Outcome bias in decision evaluation. Journal of personality and social psychology, 54(4), 569. ↩

- Fischhoff, B., & Beyth, R. (1975). I knew it would happen: Remembered probabilities of once – future things. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 13(1), 1-16. ↩