Mapping the conspiracy theory networks of mass shooting events

The world was deeply shocked this week by the Las Vegas shooting, the deadliest mass shooting in modern US history.

Much of the media reporting in the aftermath of the shooting has focused on the US gun control debate, and on the shooter, 64-year-old Stephen Paddock. Considerable surprise is being expressed that Stephen Paddock could have committed such a crime, as he was seen as a mild-mannered person who lived an apparently normal life. Although a gambler, he was wealthy with no known financial problems, and showed no obvious indications of mental illness, extreme political or religious views, or unhealthy gun interest.

However, as I discussed in a previous RealKM Magazine article, we need to look not only at the shooter. We also need to study their social networks, with research showing how US gunshot violence “follows an epidemic-like process of social contagion that is transmitted through networks of people by social interactions.”

Details of Stephen Paddock’s social networks are only just starting to emerge, but his father Benjamin was a violent career criminal who was once on the FBI’s list of 10 most wanted people. Considered dangerous and psychopathic, Benjamin Paddock had also carried out a violent attack in Las Vegas with chilling parallels to Stephen’s massacre. Adverse experiences in childhood can have significant negative impacts in later life, and while it can only be speculation at this point, Stephen Paddock could have been greatly affected by his father’s actions.

Examining networks can also provide insights into another aspect of mass shootings – conspiracy theories, or, as they are euphemistically called, “alternative narratives”.

As with previous mass shootings in the US, there has been a flood of alternative narratives in the wake of the Las Vegas shooting. As is typical of such narratives, many of the conspiracy theories have suggested that the shooting is a false flag operation. These are “covert operations that are designed to deceive in such a way that activities appear as though they are being carried out by individual entities, groups, or nations other than those who actually planned and executed them.” An example is the article headline from Veterans Today that is shown in Figure 1.

The circulation of alternative narratives in response to mass shootings had not been a focus for study until University of Washington professor Kate Starbird started to notice strange clusters while analysing social media activity. Starbird studies social media activity in the wake of disasters with the aim of seeing how it might be used for the public good, such as to aid emergency responses.

She initially didn’t take the alternative narrative activity seriously, saying “It was so fringe we kind of laughed at it,” but later realised “That was a terrible mistake. We should have been studying it.” When she then mapped the clusters of conspiracy talk, she found an emerging alternative online media ecosystem of surprising power and reach.

Starbird discusses her findings in a paper1 that was presented at the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM) in May this year.

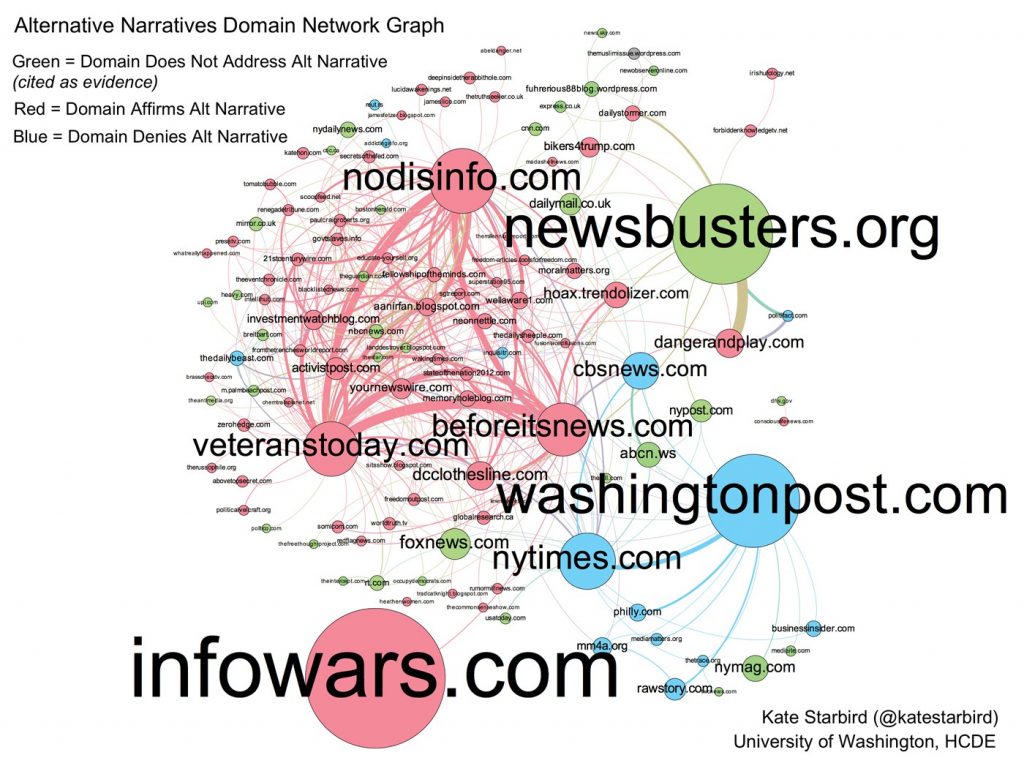

She and her team used tweeted URLs to generate a domain network, then conducted qualitative analysis to understand the nature of different domains and how they connect to each other.

The resultant network graph, as shown in Figure 2, is introduced by Stanford Magazine. Websites are represented by nodes that vary in size according to the number of mentions in the tweets. Whenever two websites are cited by the same Twitter account, the circles are connected by a line. The chart color-codes websites that affirm alternative narratives for the shootings, those that deny them and those that are used as evidence to support alternative narratives, even though they don’t directly refer to those narratives. The latter two categories include many mainstream media outlets. The first category, on the other hand, is a tangle of lines crisscrossing 80 tightly clustered nodes, each representing an outlet that produced stories espousing alternative narratives for shootings as well as other conspiracy theories.

Findings

- Not surprisingly, conversation around alternative narratives of mass shooting events was found to be largely fueled by content on alternative (as opposed to mainstream) media. Twitter users who engaged in conspiracy theorizing cited articles from dozens of alternative media domains to support their theories. Occasionally, they cited mainstream media as well, either to use details from articles about the event as evidence for their theories or to directly challenge the mainstream narrative.

- Though much of the content on the domains was focused around US politics and designed for a US audience, the agendas did not align to commonly-held notions of left (liberal) vs. right (conservative) in US politics. Instead, almost all focused on anti-globalist themes, and were highly critical of the US and other Western governments and their role around the world.

- Another theme noted across the majority of domains was the appropriation of the “fake news” argument to attack mainstream media. The websites hosted on many of these domains intentionally position their content as an alternative to mainstream media, which they claim is biased in various ways. Combating the “fake news” attack on their product, many of them responded with a counterattack.

- There is convergence within the alternative media domains around a number of “conspiracy” themes. In addition to anti-globalist and anti-media views, there was also content that was anti-vaccine, anti-GMO, and anti-climate science. Because of this, a “critically thinking” citizen seeking more information to confirm their views about, for example, the danger of vaccines may find themselves exposed to and eventually infected by other conspiracy theories.

- The same stories were found on multiple domains. This means that an individual using these sites is likely seeing the same messages in different forms and in different places, which may distort their perception of this information as it gives the false appearance of source diversity.

- Three types of sites that traffic in alternative narratives were identified. One set is “true believers”. The second promotes conspiracy theories to attract visitors to its sites for financial profit. The third (and smallest) group is spreading disinformation to advance its political interest: to undermine the credibility of US authorities and the mainstream media.

- Content supporting Russian government interests was present across a majority of the domains. For example, Veterans Today has strong ties to New Eastern Outlook, a geopolitical journal published by the government-chartered Russian Academy of Sciences. While there are only two openly Russian government-run websites in Figure 2, the study found that most of the sites contain content supporting Russian government interests.

Reference:

- Starbird, Kate. “Examining the Alternative Media Ecosystem Through the Production of Alternative Narratives of Mass Shooting Events on Twitter.” In ICWSM, pp. 230-239. 2017. ↩

Also published on Medium.