Open access to scholarly knowledge in the digital era (chapter 2.4): Intersections between artistic making and scientific knowing

This article is chapter 2.4 in section 2 of a series of articles summarising the book Reassembling Scholarly Communications: Histories, Infrastructures, and Global Politics of Open Access.

The making of empirical knowledge – that is, knowledge that is verifiable by experiment and observation – is generally regarded today as the result of research carried out by social and natural scientists. On the other hand, the arts and humanities are considered to employ a different type of methodology, form a separate realm of inquiry, and produce insights that are sometimes complementary, but not equivalent, to objective facts.

However, in the fourth chapter of the knowledge cultures section, Pamela H. Smith, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Naomi Rosenkranz, and Claire Conklin Sabel alert that the empirical techniques of experiment and observation employed in the natural sciences have their origins both in the creative labors of Renaissance artists’ workshops and in the empirical methods pioneered by Renaissance humanists and historians.

They advise that at the beginning of the Scientific Revolution in the sixteenth century, the craft workshop was understood to make knowledge about nature, as artisans codified material processes in technical recipes and “how-to” texts. The earliest European scientific societies avidly collected technical recipes from craftspeople in order to study and advance natural knowledge.

Over the course of the seventeenth century, collaboration and experimentation that had taken place within the craft workshop became integrated into the practices of the natural sciences. However, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when the new sciences cohered as distinct disciplines, these shared origins became obscured, and since then, the divisions between the natural sciences and the arts and humanities have grown ever wider.

The Making and Knowing Project

Smith and colleagues advise that studying the genre of “how-to” texts as a platform for a new type of communication of knowledge in the past provides an opportunity to bridge the modern communities of artists, historians, and scientists by fostering scholarly communication and collaboration around materials and the techniques of engaging with the material world. They support this with the case study of the Making and Knowing Project, which explores historical and methodological intersections between artistic making and scientific knowing.

The Making and Knowing Project employs new technologies to reconfigure one of these historical how-to texts for new uses and as a platform for dissemination and collaboration. From 2014 through 2020, the Project created a digital critical edition of an intriguing anonymous sixteenth-century manuscript now held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. Fr. 640.

The manuscript is investigated using techniques from the laboratory, art studio, museum, and archive. To achieve this, the Project brought together a network of over 400 collaborators in the humanities, arts, and natural sciences at institutions worldwide to undertake interdisciplinary research, teaching, and knowledge exchange on the manuscript. Thus, both the process of creating the digital critical edition as well as the resulting product together compose the platform for collaboration and dissemination.

The Project’s collaborative approach challenges the separation of the method and practice of teaching from original research, and the division between scientific and humanistic inquiry. It brings to the fore consideration of historical evidence, and indicates the important strengths of large-scale collaborative research in historical and humanities scholarship.

The Making and Knowing Project also considers how training in the hands-on skills of material and technical literacy as well as in emergent digital and open-access technologies can transform the practice of historical research by reinforcing the value of differently encoded forms of knowledge.

The early modern how-to text as a platform for knowledge-making and dissemination: BnF Ms. Fr. 640

In the last decades of the sixteenth century, an anonymous French-speaking craftsperson, most likely from the region of Toulouse, took the unusual step of setting down on paper techniques for a number of processes that we would now classify as belonging to the fine arts, crafts, and technology: drawing instruction; pigment application; dyeing; coloring of metal, wax, and wood; imitation gem production; metal and cannon casting; tree grafting; land surveying; preservation of animals, plants, and foodstuffs; distillation of acids; and much more.

Smith and colleagues advise that the resulting manuscript, now housed in France’s Bibliothèque nationale as Ms. Fr. 640, is a unique communicative record of practices that gives rare insight into craft and artistic techniques, daily life, and material and intellectual understandings of the natural world in the sixteenth century. Above all, the manuscript demonstrates the common origins of artistic and scientific experimentation and innovation in the workshops of early modern Europe (ca. 1350–1700). This document is an early example of knowledge (or research) communication.

Ms. Fr. 640’s compilation of techniques, recipes, and experimental notes produced by an experienced practitioner appeared at a pivotal moment in the growth of a new mode of gaining knowledge which we now call “empiricism” and “natural science.” The fact that a practitioner recorded these technical procedures at all was part of a seminal development in early modern European history starting around 1400, when craftspeople increasingly began to write down their embodied knowledge in “how-to texts.”

As new communities of readers and writers grew, these texts were imitated and disseminated by entrepreneurial printers to a diverse audience, helping to foster a culture that valued practical knowledge. These how-to books thus became a form of conveying both practical and scholarly activity as well as collaboration, exchange, and communication.

The Making and Knowing Project as a platform for knowledge creation and exchange

From the Project’s inception in 2014, ongoing work toward the full transcription of Ms. Fr. 640’s French text, English translation, and the research generated around the manuscript became a platform, or an infrastructure of sorts, for hundreds of scholars and students to take part in active research and extend the Project’s work to their own scholarship and teaching.

Moreover, Smith and colleagues alert that Ms. Fr. 640 is proving to be an important source of evidence across a number of disciplines, from technical art history to literary scholarship to the history of daily life. The publication of the annotated transcription and English translation of Ms. Fr. 640 as a scholarly edition has made accessible an important primary source that significantly enhances the existing body of early modern technical writing and allows readers to understand and analyze the actions of craft making as the creation of empirically tested knowledge about the natural world.

The digital critical edition of BnF Ms. Fr. 640

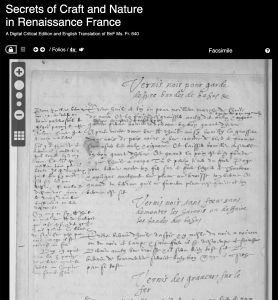

Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France: A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, hosted by the Columbia University Libraries, makes this unique manuscript freely available to students, scholars, and the general public through open access publication.

It presents the text of the manuscript in French transcription and English translation for the first time and, through the Making and Knowing Project’s customized encoding, transforms the manuscript’s text into a rich and manipulable dataset for advanced analysis, search queries, and visualization.

Moreover, Secrets of Craft and Nature situates the manuscript’s contents within the material and historical contexts in which they were produced. Users of the edition not only read the manuscript as a text but, through the laboratory reconstructions of its recipes, also experience it as a record of material practices.

To facilitate this experiential engagement, the edition harnesses the flexibility and interactivity of tools in the digital humanities in a dynamic, multifunctional, web-based application. It presents traditional archival and paleographic research on the manuscript alongside innovative material reconstructions and analyses of the techniques described in it. In this way, the open-access digital critical edition actually embodies many of the principles that are key to Ms. Fr. 640 itself.

Figure 1 shows an example of user-directed text comparison panes in the Digital Critical Edition of BnF Ms. Fr. 640. Note the pop-out commentary (editorial note at lower left of right pane) and a dropdown research essay (marked with the flask icon) that explains and reconstructs the recipe.

Comprehensive digital encoding and markup transforms the manuscript text into a database of recipes, materials, and processes, which users can freely search and analyze. An extensive search function allows users to easily find and collect information through various filters, and the raw data, openly available through GitHub, can also be used for further analysis and visualization with existing digital humanities tools.

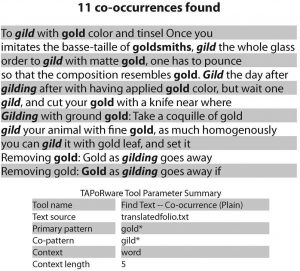

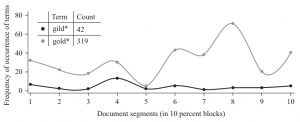

For example, a user can query the data to locate every instance of the material “gold,” and then further refine search results by the process of “gilding” to determine what proportion of gold usage is related to gilding (Figures 2–4). This database and robust search/concordance feature allows scholars, educators, and students to draw new connections among thematic focuses, specific materials, and much more from the manuscript’s contents.

Whether the manuscript is browsed or searched, the user has the option to consult relevant features of the critical commentary in pop-out windows that illuminate specific aspects of the manuscript such as a word or a technique, or the historical and cultural context of its production (figure 1). The edition’s critical apparatus includes multimedia research essays that place techniques and materials described in Ms. Fr. 640 in their textual and historical contexts, editorial comments, a glossary of technical terms, and resources for further exploration.

The multimedia essays combine traditional historical research and comparative material (for example, historical objects in museum collections produced using techniques described in the manuscript) with innovative recipe reconstructions. The essays include images, objects, graphic animations, videos, and first-person accounts of processes that cannot adequately be conveyed in traditional print formats.

In addition to the research essays that explicate material and technical content, linguistic and paleographic essays also make transparent the editors’ and translators’ interventions and interpretive decisions. The entirety of the critical apparatus is produced through student-scholar teaching-research partnerships.

Outcomes of the Making and Knowing Project

In concluding their chapter, Smith and colleagues state that at its heart, the Making and Knowing Project asks what a book was in the sixteenth century, what a book is for in the twenty-first century, and what it can do for us.

Until recently, the form of the book, as a printed document, was taken as a standard for the production and dissemination of knowledge. Current research on the early modern era has disrupted an overly simplified conception of the book, revealing that books were often collectively compiled and the idea of a single author with a proprietary right to the creative content of a text was the exception. Our assumptions that printed books superseded the inefficient and limited communication of manuscript culture have been discredited by a more sophisticated understanding of writing technologies.

Early modern knowledge was made through the circulation of many different forms of media (including letters, manuscripts, instruments, and objects – among them printed books). This proliferation of media was not entirely dissimilar to today’s blogs, zines, websites, web projects, e-books, digital databases and archives, online exhibits, streaming videos, and podcasts.

The “printed book” as a monolithic concept – containing and conveying knowledge seamlessly from author to audience – seems increasingly inadequate to describe the products of the past, let alone where we are going in the present.

However, in spite of the discrediting of this narrative, it continues to constrain scholarly and public conceptions of how knowledge is conveyed: we strive to imitate a “reading experience” on our digital humanities platforms. We “turn pages” on our devices. We view the text as if it were simply a sheet of paper, rather than metal, plastic, and liquid crystal; and we naively neglect to consider it as containing proprietary code that can be used to look back at its readers or potentially to censor text automatically.

Drawing upon a deep interest in what it means to make and communicate knowledge (a central concern of the history of science and technology), the Making and Knowing Project rethinks the book as a scholarly object for the twenty-first century from the perspective of the early modern world.

To recapture this exciting and highly experimental moment in human history and to allow people today to access it more vividly, the scholars of the Making and Knowing Project aim to think creatively with the technologies available to us today. How can we effectively present historical content and analysis in ways that communicate the dynamic and multidimensional nature of texts, especially that of a how-to text?

The Making and Knowing Project is disassembling the manuscript’s assemblage of written and practiced activity by means of unusual methodologies and research, which includes historical laboratory reconstructions and new tools in the digital humanities.

The Project’s edition combines text- and object-based historical research with laboratory experimentation, computer science, digital humanities, visualization, and design research in order to communicate the results of its investigations in ways that are intellectually rigorous, methodologically innovative, and able to draw in new audiences and participants.

As their final comment, Smith and colleagues state that an important outcome of the Project’s disassembly and reassembly of Ms. Fr. 640 has been to demonstrate that disciplinary divides between science, art, craft, and the humanities can also be dismantled in the research and publication process.

Next part (section 3): Publics and politics.

Article source: This article is an edited summary of Chapter 81 of the book Reassembling scholarly communications: Histories, infrastructures, and global politics of Open Access2 which has been published by MIT Press under a CC BY 4.0 Creative Commons license.

Article license: This article is published under a CC BY 4.0 Creative Commons license.

References:

- Smith, P.H., Uchacz, T.H., Rosenkranz, N., & and Sabel, C.C. (2020). The Making of Empirical Knowledge: Recipes, Craft, and Scholarly Communication. In Eve, M. P., & Gray, J. (Eds.) Reassembling scholarly communications: Histories, infrastructures, and global politics of Open Access. MIT Press. ↩

- Eve, M. P., & Gray, J. (Eds.) (2020). Reassembling scholarly communications: Histories, infrastructures, and global politics of Open Access. MIT Press. ↩

Also published on Medium.