The vital knowledge missing from Australia’s bushfire crisis debates: Part 2 – The popular narrative and the unpopular scientific knowledge

This article is part 2 of a two-part series exploring vital knowledge that has been missing from debates in regard to the causes of Australia’s horror bushfire crisis in the summer of 2019-20.

Over the past three months, Australia has been facing a horror bushfire crisis that has sparked a war of words in the mainstream media and on social media, particularly in regard to the causes of the fires. The debates in this regard primarily centre around two themes: the role of climate change and the role of hazard reduction burning.

In the first part of this article series, I alert that vital knowledge has been missing from these debates, and discussed the first aspect of the missing knowledge – what we can learn from climate history. The evidence I presented shows that there is a large degree of climatic variability in southeastern Australia, and that this variability is a contributing factor to the bushfire crisis in that part of Australia. But I also show that climate change is a contributing factor, and that we ignore the combined impact of climatic variability and climate change at our very great peril.

This second part of the series looks at the another aspect of the debates – the popular narrative and the unpopular scientific knowledge in regard to the role of fire in the Australian landscape.

What is the role of fire in the Australian landscape?

There are highly divided opinions being expressed in regard to hazard reduction burning, which is the managed burning of forest undergrowth plants and fallen branches and leaves with the aim of reducing the risk of later uncontrolled fires.

Some commentators argue that the fires have been caused by an excessive buildup of flammable “fuel load” material due to a lack of hazard reduction burning. Some of these critics also argue that this situation has been exacerbated by restrictive policies that prevent the conduct of controlled hazard reduction burns to reduce this fuel load. Others dismiss this, saying that hazard reduction burning has been conducted to the greatest extent possible. Then, there are others who argue that returning to Aboriginal “cultural burning” practices will solve the problem.

The popular narrative

The diverse viewpoints in regard to hazard reduction burning all have their foundation in a popular narrative. I’ve been told this story time and time again in my environmental management work. With a few minor variations, it basically goes like this:

- prior to the British colonisation of Australia from 1788 onwards, Aboriginal people managed the natural vegetation in Australia through the use of fire, and Australia’s natural vegetation evolved in response to this

- this Aboriginal burning meant that at the time of the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, the Australian landscape was largely park-like, a grassland with scattered trees

- early settlers in Australia’s growing colonies maintained Aboriginal burning practices to a large extent, continuing as a general practice for bushfire hazard reduction in forested and rural areas well into the 20th century

- the rise of environmentalism in the latter decades of the 20th century saw the emergence of concerns in regard to the ecological impacts of these burning practices

- because of this, environmentalists (often colloquially called ‘greenies’ in Australia) and Greens Party members have lobbied governments or acted directly to ban or restrict hazard reduction burning

- these bans and restrictions mean that bushland areas now have a massive and dangerous bushfire fuel load of thick undergrowth and fallen leaves and branches.

This popular narrative has been significantly reinforced by some notable popular non-fiction books. These are:

- A Million Wild Acres: 200 Years of Man and an Australian Forest1, by Eric Rolls, first published in 1981 and republished in 2011. The late Eric Rolls was a farmer and writer.

- The Future Eaters2, by Tim Flannery, first published in 1994 and republished in 2002. Professor Tim Flannery is a well-known commentator on climate change, and currently the Chief Councillor of The Climate Council. He also has expertise in mammal studies and paleontology, and was named Australian of the Year in 2007.

- The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia3, by Bill Gammage, published in 2011. Bill Gammage is an academic historian and Emeritus Professor at the Humanities Research Centre of the Australian National University (ANU).

Rolls sowed the seeds of the popular narrative in A Million Wild Acres, which he wrote about the Pilliga Forest, located in the north west of the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW). A report by ABC Radio National states that in writing the book:

Eric Rolls uncovered a story of conflict and colonisation at a time when few had heard it – of how the Aboriginal people who’d been maintaining open pastures across that country through use of fire, were violently forced off their land. In their absence, the bush took over. The result was the Pilliga Scrub. His great forest wasn’t ancient, wrote Rolls; it had grown up thanks to European land grabs.

Then in The Future Eaters, Flannery proposes that Aboriginal “firestick farming” practices significantly altered the flora and fauna of Australia, and that these practices were clearly evident to the early explorers:

The use of fire by Aboriginal people was so widespread and constant that virtually every early explorer in Australia makes mention of it. It was Aboriginal fire that prompted James Cook to call Australia ‘This continent of smoke’. Tasman, as early as 1642, saw smoke billow into the sky for days at a time, as did other early explorers. But it was that most poetic of explorers, Ernest Giles who, during his travels in Central Australia, gave us the most vivid image of the inseparability of fire and Aborigines: “The natives were about, burning, burning, ever burning; one would think they were of the fabled salamander race, and lived on fire instead of water.”

Gammage further reinforces the popular narrative in his book The Biggest Estate on Earth, How Aborigines made Australia. In a media article coinciding with the publication of his book, he wishes for a return to the Aboriginal fire management practices that he concludes were evident at the time of the First Fleet in 1788, stating that:

We should burn more. After Victoria’s February 2009 fires, I saw on TV how joyous people were at the bush regenerating green. I was dismayed. Another fire cycle was beginning, to end in another killer fire 40 or 50 years on. In 1788 people would never have let that happen, because their children could not have survived the inevitable holocaust. Instead, in autumn and winter 2009 they would have burnt off big patches of new growth, with small cool fires. Most scrub species need hot fire to regenerate, so with cool fires the mid-height scrub layer that would otherwise lift flames from ground to canopy never takes hold. It was no accident that newcomers delighting in 1788’s parks so often reported no “underwood”. That not only made parks, it was a vital fuel control.

Many people oppose frequent burning. Black ground is ugly and dirty, smoke is unpleasant and unhealthy, causes asthma, dirties the washing and so on. All true, but does it justify letting killer fires build up? And can the result really remain ugly when so many early newcomers praised how much country was park-like? Of course, we must make more smoke now than then, because we have let scrub and forest fuel build-up. It is a daunting task to return to 1788’s safer balance, but 1788 shows us the rewards if we do. If you know how to use fire, you can manage any vegetation, from spinifex to rainforest.

The unpopular scientific knowledge

The perspectives put forward by Rolls, Flannery, and Gammage have been widely promoted through the media, and as a result many Australians, including a number of my environmental management colleagues, now accept these perspectives as indisputable fact.

But what has received far less attention in the media are the evidence-based perspectives of a much wider range of scientists who have published their research and analyses in peer-reviewed academic journals. These scientists don’t hold back in their damning criticisms of Flannery.

In an article in the Sydney Morning Herald titled “The Flannery Eaters”, Dr Stephen Wroe, a palaeontologist at the University of Sydney, is quoted as saying:

Just because a guy is well known does not mean he knows what he is talking about. I’ve got a fairly cynical view of Tim. He’s an opportunist. He knows climate change is a buzzword, but a few months’ work does not make him an expert.

The same article also quotes Dr Judith Field, an archaeologist at the University of Sydney, as saying that:

Tim doesn’t let the facts get in the way of a good story. He does a lot of broadbrush stuff, with broad consequences, and some of it is just plain wrong … Most of our hypotheses are tested with facts, and that underlies the work we do. But most of what Tim does is conceptually driven, and not based on data. And he has been selective in his use of data.

The article goes on to document the criticisms of Jim Allen, an archaeologist at La Trobe University, and John Benson, senior plant ecologist at the Botanic Gardens Trust in Sydney.

Field and Benson are also among the several critics who responded to Flannery’s Aboriginal burning hypotheses as part of commentary on the televised version of The Future Eaters.

John Benson and colleague P. Redpath have criticised Rolls’ and Flannery’s views as part of a comprehensive critique of a booklet titled The Australian Landscape – Observations of Explorers and Early Settlers4, which was prepared by D.J. Ryan, J. Ryan and B. Starr and published by the Murrumbidgee Catchment Management Committee in the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW). Rolls’ and Flannery’s work were references for the booklet.

In their critique, which was published in the botanical journal Cunninghamia5, Benson and Redpath state that:

The quotes used in Ryan et al. (1995) mainly cover parts of south-eastern Australia between Tasmania and Brisbane, but do not deal with particular regions in a systematic way. They generally refer to one type of vegetation formation – grassy woodland, which mainly occurs on clayey soils in drier coastal valleys, on non-siliceous soils on the undulating tablelands and on the western slopes. The explorers may have favoured travelling through these areas because they occur near rivers (water), had an open understorey and because some explorers were employed to seek out suitable grazing lands. Using three historical estimates of tree density in grassy woodlands, we estimate there was an average of 30 large trees/ha spaced about one tree width apart. This contrasts with Rolls’ estimate of 4 large trees/ha and the perceptions of Ryan et al. (1995) about the structure of a woodland. We found frequent references in the explorers’ journals to vegetation containing a dense understorey including coastal heath, shrublands, rainforest and dense eucalypt forests. We found no evidence that most of south-east Australia’s vegetation was annually burnt by Aboriginal people and provide examples where explorers’ notes about fire have been misinterpreted or inappropriately extrapolated by Ryan et al. (1995) and Flannery (1994).

While some journal entries reveal that Aboriginal people used fire for cooking and burning the bush, the extent, frequency and season of their use of fire is largely unknown, particularly for southern Australia. Vegetation types such as rainforest, wet sclerophyll eucalypt forest, alpine shrublands and herbfields, and inland chenopod shrublands, along with a range of plant and animal species,would now be rarer or extinct if they had been burnt every few years over the thousands of years of Aboriginal occupation. Furthermore, Ryan et al. (1995) and Flannery (1994) ignore much evidence that points to climate as being the main determinant in vegetation change over millions of years, with major changes occurring since the onset of aridity in the Miocene but continuing through the last ice age, which coincided with the occupation of Australia by Aboriginal people.

The adaptation of many plant species to aridity, drought, low nutrient soils and fire does not imply a requirement for them to be frequently burnt.

Flannery replied6 to Benson and Redpath’s critique, arguing that they had relied on the quotes of Ryan et al. rather than Flannery’s original work, and also that he had been misquoted by the media. However, in their response7 to Flannery’s reply, Benson and Redpath state:

We concluded that Flannery’s views about the nature of pre-European vegetation and fire regimes do not hold up against a range of biological evidence and we cited references to support this. We substantiated from the literature, that the pre-European vegetation was much more heterogeneous than he suggests. It was not solely dominated by grassy open woodlands or grassland …

Flannery’s views on pre-European Aboriginal burning regimes are questionable. From what we know about many species’ responses to fire, frequent burning (1–4 years) could not have been practised universally. Aborigines burnt different vegetation types differently depending on what resources they were extracting. Some vegetation types were not, or infrequently burnt …

Flannery considers he was mis-quoted. We cannot prove or disprove this, but the damage was done.

David Bowman, another of the several critics who responded to Flannery’s Aboriginal burning hypotheses as part of commentary on the televised version of The Future Eaters, criticises the views of both Flannery and Gammage. Bowman is Professor of Environmental Change Biology at the University of Tasmania. He states that:

There are two well-known narratives about Aboriginal fire use.

One, popularised by Tim Flannery, stresses the ecologically disruptive impact of Aboriginal fire use. This storyline argues that the megafauna extinctions that immediately followed human colonisation in the ice age resulted in a ramping up of fire activity. This then led to the spread of flammable vegetation which now fuels bushfires.

Another, promoted by Bill Gammage, suggests that the biodiverse landscapes that were colonised by the British were the direct product of skilful and sustained fire usage.

Such broad-brush accounts give the impression that the specific details of Aboriginal fire usage are well-known and can be generalised across the entire continent. Sadly this is not the case.

So rapid was the socio-ecological disruption of southern Australia that researchers have had to rely on historical sources, such as colonial texts and images, and tree rings, pollen and charcoal in lake sediments, to piece together how Aboriginal people burned the land.

Such records are open to interpretation and there remains vigorous debate about the degree to which Aboriginal people shaped landscapes.

As I discussed in a previous case study in RealKM Magazine, the dispossession of Aboriginal people from their land was swift and brutal in southeastern Australia, and this has led to the significant loss of a large degree of traditional knowledge in this region.

However, as Bowman documents, traditional fire management knowledge in much of northern Australia hasn’t been subject to the same degree of cultural genocide. These northern Australia fire management practices now constitute much of what is known about Aboriginal fire regimes in Australia, so there’s the temptation to believe that these practices can be applied more broadly. However, northern Australia has very different vegetation communities and significant differences in climate, so this is inappropriate. As Benson and Redpath articulate, we need to carefully study the species composition of the vegetation communities of southeastern Australia and learn as much as we can about their fire history, and use proven science to determine the most appropriate fire regimes. This work has actually been underway for a long time, but rarely receives media attention.

This isn’t the only example of where a popular environmental narrative put forward by a few prominent people has been seriously challenged by a wider body of other scientists. As I’ve previously discussed in RealKM Magazine, another example is the Easter Island ecocide theory.

A case study

I first encountered the popular narrative after taking on the management of a bushland property in the upland areas of the southern Lockyer Valley, located about 100km west of Brisbane, the capital city of the Australian state of Queensland. The property, called “Treetop Sanctuary”, was being established as a small-scale health retreat / environmental tourism enterprise.

As I discuss in a paper8 that I presented at the 1998 World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF) South-East Queensland Rainforest Recovery Conference, an evidence-based assessment of the vegetation and fire history of the Treetop Sanctuary property did not support the popular narrative.

There had been no significant fire on the Treetop Sanctuary property for at least 20 years, and a large quantity of fallen timber and leaf litter had accumulated on the forest floor, increasing the risk of a serious wildfire. Many landholders in the area around Treetop Sanctuary were burning annually or every few years to reduce the accumulated fuel load, with some also burning to promote the growth of fresh grazing pasture.

This hazard reduction and pasture maintenance burning was typically justified by the expressed belief that “the Aborigines burnt this every year”, reinforced by the observation that “this country was all open 20 years ago”. It was widely believed that before European colonisation, Aboriginals burnt the bushland of the Lockyer as frequently as every year. However, this could not be correct, because many of the Lockyer Valley vegetation types and species would simply not be present if fire had been used as frequently as every year or even as frequently as every five years.

This certainly was the case with the vegetation of the Treetop Sanctuary property. As well as areas of dry rainforest, which are destroyed or seriously degraded by fire, the tall open woodland covering around 60% of the property featured a dense midstorey and understorey dominated by a rare and threatened Acacia and Boronia species. The Boronia species was the spectacular pink-flowered Boronia splendida (see header image above).

I would later have this confirmed when leading a walk in the nearby Dwyer’s Scrub Conservation Park for a group of visiting ecologists from South Africa. As we walked through the same tall open woodland ecosystem that is also found on the Treetop Sanctuary property, these ecologists were astounded to observe a vegetation community that was identical to one they had been studying in South Africa. While there were slight differences in the plant species, the species families were the same. This means that the ecosystem is very likely a relic from the ancient super-continent Gondwana, little changed over millions of years, and not the product of Aboriginal burning. A number of Gondwana-era species have already been identified in Australia, for example the nightcap oak which has been horrifically devastated in the bushfire crisis.

Aboriginal people burnt bushland areas to assist with the availability of food resources, hence the description “fire-stick farming”. The Lockyer Valley features wide and very fertile creek valleys and alluvial plains, now recognised as some of the world’s most fertile agricultural land. Prior to European colonisation, these lowland areas typically featured open woodland with a grassy understorey and would have had an abundance of food resources, in particular kangaroos and wallabies. The Aboriginal people apparently lived a semi-sedentary lifestyle on the lowland flats and plains, only venturing into the uplands on hunting and food gathering forays or to travel on various pathways to other areas9.

The lowland flats and plains were probably burnt to promote the presence of fresh green grass to attract the kangaroos and wallabies, and there is historical evidence to support this. For example, Murphy’s Creek in the north-west of the Lockyer Valley is reported to have been known to Aboriginal people as Tamamareen meaning “where the fishing nets were burnt in a grass fire” 10. However, they would have had little or no need to burn the far less fertile Lockyer uplands. Fire would actually have posed a significant threat to the upland dry rainforest areas, which featured food and medicinal resources, and for this reason fire may have even been deliberately avoided in the uplands.

There is evidence to support the view that different tribal groups had very different fire management practices. Just over a small range to the south of the Treetop Sanctuary property is the West Haldon district, which was apparently a different tribal area with dramatically different fire management practices. The local history book On the Point of a Spur11 highlights the differences between the two areas:

Unlike the impenetrable scrub country that surrounded the Mt. Whitestone district in the early 1840’s, the West Haldon district bordering the south-west Lockyer was open country. May Cork writes:

It is worth recording that a description of the district in the early 1860’s differs considerably from a description of it at present. At the date mentioned the country was sparsely timbered and well grassed. Soon however, a remarkable change took place and such country became overgrown with small brush, and the number of trees increased enormously.

Most certainly, the change in vegetation cover at West Haldon from a sparse sclerophyll forest to a densely timbered one was due to the removal of the Keinjan tribesman from the area by 1860, who previously practised extensive burning of their hunting grounds.

This isn’t at all surprising. The West Haldon district is part of the eastern Darling Downs, which has a very different landscape and geology, and therefore different native vegetation communities, to the adjacent upland areas of the southern Lockyer Valley. It made perfect sense for the Aboriginal people of the eastern Darling Downs to regularly use fire to maximise food resources in their landscape, and also for the Aboriginal people of the upland areas of the southern Lockyer Valley to use a range of different fire regimes in their much more complex landscape, including fire exclusion in some ecosystems. Indeed, the Aboriginal people of the eastern Darling Downs were known by the coastal tribes as the Gooneburra – meaning “fire people” – because of their much greater use of fire12.

In contrast to the reason for the “open country” observations of the West Haldon district, the observation that “this country was all open 20 years ago” in regard to the area that included the Treetop Sanctuary property was due to a decades-long cycle of change.

Because it is dependant on a 20-plus year fire cycle, the vegetation on the Treetop Sanctuary property goes through observable changes. When there has not been a fire for more than 20 years, the dominant midstorey of Acacia reaches maturity and dies, meaning that the midstorey becomes quite open or even completely open. Following a fire, there is rapid regeneration of the understorey, midstorey, and also of new overstorey plants, which quickly creates a very dense and impenetrable undergrowth.

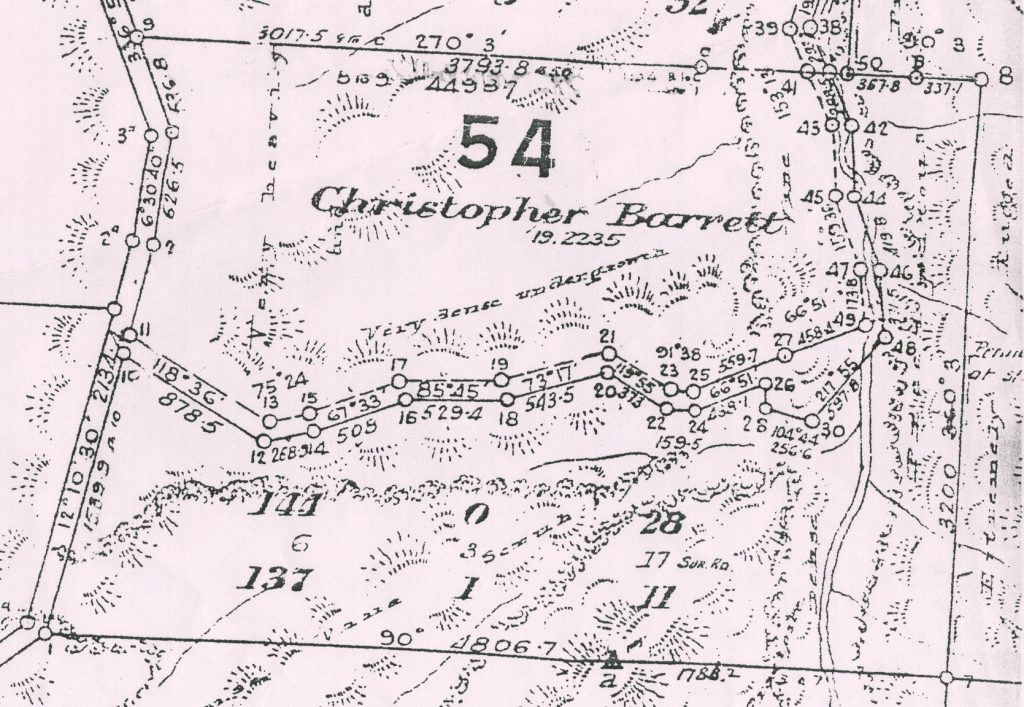

At the time of the conference paper presentation in 1998, the progression to a more open stage was clearly observable on the Treetop Sanctuary property, with much of the Acacia midstorey dying over the previous five years. It is the open stage that local landholders were observing when saying that “this country was all open 20 years ago”, not realising that it is just a stage within a cycle. While local landholders remember the open stage of the cycle, the surveyor who carried out the original 1886 survey of the Treetop Sanctuary property over 100 years ago struck the dense undergrowth stage. This is reflected in his “very dense undergrowth” and “very heavily timbered” comments for the woodland parts of the Treetop Sanctuary property, as shown in the following survey map:

At some point, Boronia splendida would also be expected to reach maturity and die, which would open up the understorey and midstorey even further, but at the time of the conference paper presentation in 1998 there was not yet any sign of this occurring.

Because of the significance of the vegetation and the unlikelihood that it was deliberately burnt by Aboriginal people, the fire management approach for the Treetop Sanctuary property aimed at hazard protection rather than hazard reduction. Hazard protection works on the “rule of 3B’s”: Buildings – Buffer – Bushland. A buffer zone is used to provide a line of defence between buildings and bushland.

The buffer zone needs to be kept completely clear of understorey, midstorey, and any fuel load. Fuel load removal in the buffer zone can be achieved through manual removal (picking up branches, raking leaves) or by controlled burning. The overstorey (trees) should also be removed from the buffer zone if local conditions indicate a high risk of crown fires, that is, fires that travel rapidly through the tree tops rather than at ground level. A fireline is constructed along the boundary between the buffer zone and the bushland. This facilitates easy access for back burning in case of an approaching wildfire, and also provides a firebreak for controlled burning operations within the buffer zone. A second fireline can also be constructed between the buildings and the buffer zone. Additional firelines should also be constructed within the bushland areas if possible, as was done on the Treetop Sanctuary property, to provide additional lines of defence. Firelines and buffer zones should also be constructed to assist in preventing wildfires moving to or from adjacent properties.

Recognising socio-ecological complexity

As was indicated in the conclusion of my 1998 paper13 discussed in the case study above, in that year I went on to become one of the founding members of the South East Queensland Fire and Biodiversity Consortium, which recently celebrated its 20th anniversary, and also a member of the Consortium’s Fire Management Planning Working Group.

The South East Queensland Fire and Biodiversity Consortium has produced guidance on the different fire regimes needed by the various ecosystems found in the region, and also a range of other useful resources to assist fire management including a Property Fire Management Planning Kit. The Consortium developed the kit as an adaptation of an earlier fire management planning kit that had been developed by Marc Gardner as part of the Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills Project, which I coordinated in 1998-99. In turn, this kit had been adapted from an earlier kit prepared for the Shire of Yarra Ranges in the Australian state of Victoria.

I also went on to prepare a comprehensive Biodiversity Recovery Plan for the Lockyer Valley that recognised and planned for the ecological complexity of the area, including the different fire requirements of the area’s diverse array of significant species and ecosystems. Recognising that one person can’t possess all of the expertise and knowledge needed for such planning, the preparation of the Biodiversity Recovery Plan was overseen by a diverse team of experts in ecology and land planning. The Biodiversity Recovery Plan also operated in conjunction with a number of other activities that addressed the social complexity of the area, for example the Gatton Shire Biodiversity Strategy and Land Use Planning Handbook for the Lockyer Catchment.

These very effective fifth generation of knowledge management for development14,15 approaches stand in stark contrast to the “unsupported and simplistic notions about pre-European fire frequency and the composition and structure of vegetation” that Benson and Redpath identify16 as underpinning the popular narrative.

Header image: Boronia splendida by Bruce Boyes is licensed for reuse under a CC BY 4.0 Creative Commons Licence.

References:

- Rolls Eric, C. (1981). A Million Wild Acres: 200 Years of Man and an Australian Forest. Melbourne: Nelson. ↩

- Flannery, T. (2002). The Future Eaters. New York: Grove Press. ↩

- Gammage, B. (2011). The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ↩

- Ryan, D.G., Ryan, J.E. & Starr, B.J. (1995) The Australian landscape – observations of explorers andearly settlers (Murrumbidgee Catchment Management Committee: Wagga Wagga NSW). ↩

- Benson, J. S., & Redpath, P. A. (1997). The nature of pre-European native vegetation in south-eastern Australia: a critique of Ryan, DG, Ryan JR and Starr, BJ (1995), The Australian landscape: observations of explorers and early settlers, Cunninghamia, 5(2), 285-328. ↩

- Flannery, T. F. (1998). A reply to Benson and Redpath (1997). Cunninghamia, 5, 779-781. ↩

- Benson, J. S., & Redpath, P. A. (1998). A response to Flannery’s reply. Cunninghamia, 5(4), 782-785. ↩

- Boyes, B. & Cox, N. (1999). A Fire at Treetops? – Fire Management and Nature Conservation. In: Boyes, B. R. (ed.) Rainforest Recovery for the New Millennium. Proceedings of the World Wide Fund For Nature 1998 South-East Queensland Rainforest Recovery Conference. Sydney: WWF. ↩

- Ann Wallin & Associates (1998). Helidon Hills. A Predictive Cultural Heritage Report. ↩

- Ann Wallin & Associates (1998). Helidon Hills. A Predictive Cultural Heritage Report. ↩

- Campanaris, C. (1986). On the Point of a Spur. A History of the Mt. Whitestone State School, 1886 – 1986 and District. ↩

- Steele, J.G. (1983). Aboriginal Pathways in Southeast Queensland and the Richmond River. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press. ↩

- Boyes, B. & Cox, N. (1999). A Fire at Treetops? – Fire Management and Nature Conservation. In: Boyes, B. R. (ed.) Rainforest Recovery for the New Millennium. Proceedings of the World Wide Fund For Nature 1998 South-East Queensland Rainforest Recovery Conference. Sydney: WWF. ↩

- Cummings, S., Regeer, B. J., Ho, W. W., & Zweekhorst, M. B. (2013). Proposing a fifth generation of knowledge management for development: investigating convergence between knowledge management for development and transdisciplinary research. Knowledge Management for Development Journal, 9(2), 10-36. ↩

- Cummings, S., Kiwanuka, S., Gillman, H., & Regeer, B. (2018). The future of knowledge brokering, perspectives from a generational framework of knowledge management for international development. Information Development, https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666918800174 ↩

- Benson, J. S., & Redpath, P. A. (1998). A response to Flannery’s reply. Cunninghamia, 5(4), 782-785. ↩