The case for indigenous knowledge systems and knowledge sovereignty (part 12): Reflections on ways forward

This article is the final part (part 12) of a series of articles putting forward the case for indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) and knowledge sovereignty, featuring selected excerpts from the book Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders.

I have a foot in both of the worlds described … [in this series of articles]. While very appreciative of the world inhabited by the pastoralists, and having documented the logic and rationale they employ in order to make sense of, and thrive in, their environments, I also inhabit the world of scientists. This position in relation to the debates enables me to understand the forces that push the two worlds apart, and to reflect on the gap between them and on what can be done to bridge them. [The] … book [Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders] is written in the spirit of sharing the knowledge of the pastoral communities and finding ways to align it with what is deemed to be superior scientific knowledge.

Reaffirming indigenous knowledge

What comes out in this analysis is how pastoralist knowledge is being suffocated because of the primacy given to ‘scientific knowledge’. Pastoralist knowledge – despite being more context-appropriate than, and in many instances superior to, ‘scientific’ knowledge – is not taken seriously. This reminds me of a point argued by Grosfoguel1; he says, ‘Unlike other traditions of knowledge, the western is a point of view that does not assume itself as a point of view. In this way, it hides its epistemic location, paving the ground for its claims about universality, neutrality and objectivity’. In other words, ‘the western’ – which in this instance can be read as ‘the scientific’ – is a point of view that considers itself to be not a point of view, but the truth.

Much of the ‘scientific’ knowledge that underpins approaches to development in pastoral areas has a history, and emerges out of a particular time and location2. The location, however, is hidden behind a language of objectivity and universality, implying it should be accepted everywhere. However, the reality, to use the title of Walter Mignolo’s3book, Local Histories/Global Designs, is where local history is used as a global (objective) baseline against which the Beni-Amer are being judged. This would not work in reverse: we would be considered crazy if we took indicators from Africa and then used them to judge agricultural systems in the West. Treating scientific knowledge as ‘universal’, when it is in fact a ‘local knowledge’, means that the Beni-Amer, despite having valid sets of knowledges, are disqualified. On a philosophical level, this can be tied back into the promise of modernity, that (European) man believed that through science and technology he would have control and mastery of nature.

Democratising knowledge

If one takes Latour4 seriously, especially his idea that Europe – and European knowledge as a baseline – is an exercise in exoticism, what happens if, rather than viewing the debate as it is currently is, as one of ‘indigenous’ knowledge from the margins needing to be incorporated into an ‘objective centre’, we locate both sets of knowledges and give neither immediate primacy, and say, ‘Here are two knowledges coming out of different locations with different histories, and both are potentially valid’. So one set of knowledges arises out of the Beni-Amer and is located in the study region, and the other arises out of scientific knowledge and is located in Europe/the West. By getting rid of the baseline, we put the knowledges

on equal footing. Thus the prefixes of ‘indigenous’ and ‘scientific’ knowledge do not denote worth or value, but only the locations in which the knowledges we want to put into conversation with each other arise. Saying they are of equal value makes hybridisation an exercise in democracy.

I use the term democracy as Fraser5 defines it, as ‘a process of communication across differences, where citizens participate together in discussion and decision making to collectively determine the conditions of their lives’. And then the question becomes; How do we communicate across the differences? What are the criteria that we are using to judge effectiveness, and so on? These I have already established in … [Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders] by highlighting the importance of food sovereignty and knowledge sovereignty.

Shih6 describes how, in academic circles, IK has essentially been relegated to the status of a second-class citizen in comparison to its occidental cousin. However, there are those who are responding by attempting to change this. Shih states, ‘Starting with the idea of Indigenous knowledge sovereignty, we envision a determination to made Indigenous Peoples . . . the ‘subject’, rather than ‘object’, of Indigenous research and education’. With this in mind, the College of Indigenous Studies at National Dong Hwa University in Taiwan was established in 1991 to show the government’s commitment to enhancing indigenous education as well as research. It is probably unique in the world in being a faculty dedicated to local indigenous studies. So we can see that, even in academic circles dominated by the occidental paradigm, IK is beginning to find ways to raise its voice as an equal.

There is ample evidence to show that IK responds and adapts itself to new situations and imperatives in order to service the community that uses it. It is not, however, in simple adaptation that we see the true strength of IK, but rather in IK’s ability and willingness to adopt principles and practices from other systems of knowledge. This ability to extract information and practices from elsewhere and incorporate them into one’s own knowledge system is one of the quintessential expressions of knowledge sovereignty, that is, the power to use one’s own system of knowledge to evaluate an integral component of another knowledge system and pronounce it worthy or unworthy of incorporation into one’s

repertoire of knowledge and practice.

Building alternative futures

Finally, we turn to the future as something that needs to be built and constructed. So, rather than having a universe imposed, we don’t reject universality, but, like Latour7, we say a common universe needs to be constructed through an exercise of knowledge democracy.

Under the current system the basis (both social and resource) upon which the knowledge systems of the Beni-Amer depend is being systematically undermined. A variety of possible and viable potential futures are being denied the chance to be built, for reasons that are more political than scientifically legitimate (given that science is meant to be an exercise in uncovering truth).

Therefore, if things continue as they are, the knowledge that sustains the Beni-Amer will be suffocated to death: it won’t have failed, it will have been killed.

With new challenges ahead and rising demand for meat, the integration of livestock systems within the agroecology debate could be a way forward. Applying agroecology to the question of animal health would imply focusing on the causes of animal diseases in order to reduce their occurrence. Major attention will therefore be given to choosing animals adapted to their environment and using a set of management practices that favour animal adaptations and strengthen their immune systems8, a practice which is inherent in the IKS of the Beni-Amer, as outlined in … [Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders].

The interaction between livestock and vegetation is a principle that pastoral communities embody. Extensive livestock grazing is an excellent example of managing biodiversity and soil fertility. For example, through the transport of seeds and insects by livestock, the migration of pastoralists and their flocks supports habitat connectivity and biodiversity9.

Adaptive pastoral practices, such as crossbreeding more resilient cattle to combat raiding by intruders, demonstrate the integral role of IK in a sustainable future. As national governments focus more on private investments, such as crop intensification, mining and tourism, and thereby are complicit in land grabbing, they fail to see not only the economic value of pastoralism, but also how the holistic nature of indigenous pastoral practices and traditional land management is key to a sustainable future. The undermining of customary law brings tensions between the objectives of customary and national laws into play. Consultation with pastoral communities in this process is often inadequate or non-existent, and pastoralists are losing access to and control over their lands, which leads to conflicts among other land users10. This highlights the need for more productive and resilient herds. Food sovereignty, therefore, cannot be achieved without secure pastoral land rights.

In addition, policy makers still interpret practices such as livestock mobility and negotiated and reciprocal access to pastures and water as ‘coping’ mechanisms in response to scarcity, rather than as what they really are: proactive husbandry strategies that exploit variability to manage uncertainty and maximise productivity11. For these reasons, indigenous pastoral practices have an in-built flexibility and adaptability, and they have evolved by building on the strengths of scientific knowledge through tried and tested formulas. Mobile technology has enhanced the ability of herders to locate good-quality grazing areas, and freed them to explore other livelihood opportunities, which is changing the power dynamics between genders and generations.

As pastoralists are more marginalised than the settled population, and are not offered access to education, they are not able to make or influence decisions about land and water access that impact their daily life. They do their best to adapt to changing situations, using their indigenous knowledge. However, such knowledge needs to be interlinked with scientific knowledge if sustainable development and modernisation of the sector are the goal12. In addition, the recognition of local innovativeness by pastoralists provides an entry point for a bottom-up approach to supporting adaptation to much more than climate change13.

Attempts to replace traditional land use practices with modern techniques have simply exacerbated poverty, degradation and conflict. ‘In the face of climate change and increasing uncertainty in the drylands, the need to reframe policy and practice has never been greater. The future must be built on sound scientific information, local knowledge, informed participation and the wisdom of customary institutions that emphasise social equity, ecological integrity and economic development’ 14. The recognition of IK and the integration and hybridisation of different knowledge systems must be taken on board by both researchers and policy makers.

Challenges are here to stay, and it will be the duty of the next generation of scientists, policy makers, social movements, the communities and other stakeholders to salvage the situation, and I hope … [Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders] contributes to that struggle – which is going to be tough, but winnable. In Nelson Mandela’s great spirit, ‘after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb’ 15. Nothing is impossible.

Article source: Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

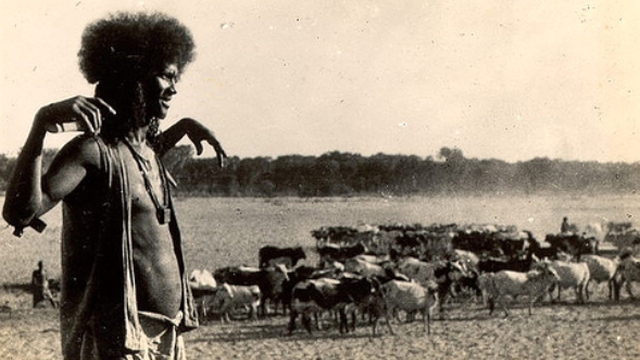

Header image source: Tigre man from Barka Valley is in the Public Domain. The Beni-Amer people probably emerged in the fourteenth century AD from the intermixing of the Beja and the Tigre.

See also: Cultural awareness in KM.

References:

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2009. ‘A Decolonial Approach to Political-Economy: Transmodernity, Border Thinking and Global Coloniality.’ Kult 6 (special issue: Epistemologies of Transformation: The Latin American Decolonial Option and its Ramifications): 10–38. ↩

- Sullivan, S. and K. Homewood. 2003. ‘On Non-Equilibrium and Nomadism: Knowledge, Diversity and Global Modernity in Drylands (and Beyond).’ CSGR Working Paper no. 122/03. Centre for the Study of Globalisation and Regionalisation, University of Warwick. ↩

- Mignolo, W. 2000. Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ↩

- Latour, Bruno. 2011. ‘Politics of Nature: East and West Perspectives.’ Ethics & Global Politics 4 (1): 71–80. ↩

- Fraser, Nancy 1996. ‘Equality, Difference, and Radical Democracy. The United States Feminist Debates Revisited.’ In D. Trend (ed.), Radical Democracy: Identity, Citizenship, and the State, 197. New York: Routledge. ↩

- Shih, Cheng Feng. 2010. ‘Academic Colonialism and the Struggle for Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Taiwan.’ Social Alternatives 29 (1): 44–7. ↩

- Latour, Bruno. 2004. ‘How to Talk about the Body? The Normative Dimension of Science Studies.’ Body & Society 10 (2–3): 205–29. ↩

- Soussana, Jean-François, Muriel Tichit, Philippe Lecomte and Bertrand Dumont. 2015. ‘Agroecology: Integration with Livestock.’ In Agroecology for Food Security and Nutrition: Proceedings of the FAO International Symposium, 18–19 September 2014, Rome, Italy, 225–49. Rome: FAO. ↩

- Florin, Madeleine and Diana Quiroz. 2016. ‘Editorial: Pastoralists and Agroecology.’ Farming Matters, December: 6–7. ILEIA. ↩

- Florin, Madeleine and Diana Quiroz. 2016. ‘Editorial: Pastoralists and Agroecology.’ Farming Matters, December: 6–7. ILEIA. ↩

- Krätli, Saverio. and Nikolaus Schareika. 2010. ‘Living Off Uncertainty: The Intelligent Animal Production of Drylands Pastoralists.’ European Journal of Development Research 22 (5): 605–22. ↩

- Sulieman, Hussein M. and Abdel Ghaffar M. Ahmed. 2013. ‘Monitoring Changes in Pastoral Resources in Eastern Sudan: A Synthesis of Remote Sensing and Local Knowledge.’ Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice 3 (1): art. 22. ↩

- GebreMichael, Yohannes, Saidou Magagi, Wolfgang Bayer and Ann Waters-Bayer. 2011. ‘More than Climate Change: Pressures Leading to Innovation by Pastoralists in Ethiopia and Niger.’ Paper presented at the International Conference on the Future of Pastoralism, 21–3 March, organised by the Future Agricultures Consortium at the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex and Feinstein International Center of Tufts University. doi:10.1.1.417.2119. ↩

- Hesse, Ced. 2011. ‘Ecology, equity and economics: reframing dryland policy.’ Opinion, November. IIED, London. ↩

- Mandela, N. 1994. Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela. London: Little, Brown. ↩