As social media plays an ever greater role in how we find and consume information, concerns have grown about the prevalence of filter bubbles and groupthink. New research from Berkeley Haas highlights how easy it is for groupthink to emerge in large groups and especially on social media.

As social media plays an ever greater role in how we find and consume information, concerns have grown about the prevalence of filter bubbles and groupthink. New research from Berkeley Haas highlights how easy it is for groupthink to emerge in large groups and especially on social media.

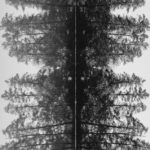

The researchers asked volunteers to participate in an online game that tasked them with identifying what they saw in various Rorschach inkblots.

“In small groups, there was a ton of variation in how people described the shapes,” the researchers say. “As you increase the size of the group, however, rather than creating unpredictability, you could actually increase your ability to predict the categories.”

Thinking alike

It’s not so much that the large groups suffer from a paucity of ideas, as the larger groups tended to have more categories for blots proposed. It’s just that in larger groups some categories were more popular than others, and as more people communicated with one another, these categories gradually won out. This resulted in outcomes coalescing, even when the blots themselves varied.

“When you’re in a small group, it’s more likely for unique perspectives to end up taking off and getting adopted,” the researchers say. “Whereas in large groups, you consistently see ‘crab’ win out because multiple people are introducing it, and you get a cascade.”

What is perhaps most interesting is that the researchers were easily able to manipulate the way in which opinions converged by the use of artificial bots into the conversations. These AI-based actors would regularly suggest that the blots looked like a sumo wrestler, and despite this previously being an unpopular category, the human volunteers gradually converged upon the same idea.

Malign influence

The tipping point seemed to be around 37%, after which the group began to adopt the sumo wrestler vision over all other categories. This was even the case when people were shown the blots that had previously been viewed unanimously as a crab.

“We showed people the crabbiest crab, and now people said it looked like a wrestler. No one described it as looking like a sumo wrestler, let alone like a person, in the large groups without bots,” the researchers say.

It’s a phenomenon that the researchers believe is clearly visible on social media, especially on Twitter where bots are such an active part of the community. The repeating of ideas, whether by human or artificial users, can easily sway a majority to think a certain way.

Content moderation

It’s why the issue of content moderation is such an important one for the social media platforms to get right. By focusing on purely delineating between real and fake news, the researchers believe they may be doing more harm than good.

“Just by trying to put out the fire in the moment, they are sending the message that this is the right category,” they say, “while a different category system may allow for more nuance and subtlety.”

They argue that a better approach would be to focus efforts on removing bots that spread categories to begin with. They cite the example of the naming of various coronavirus variants, for instance, as while scientists have been using names like 501.Y2 and B.1.1.7, the public have converged on geographical nomenclature, such as South African and UK variants, which obviously run the risk of stigmatizing those regions.