I never thought of diversity as being important. As an Asian-American high school student, I was angry about diversity. Why must I be the one to score higher on my tests? Why do I need to get better grades? Why is the bar set so much higher for me?

Silicon Valley has been dealing with complaints about its lack of leadership diversity, with a disproportionate number of white males landing at the top of tech’s hierarchy. Relatedly, many have observed the seemingly endless array of frivolous “first world problems” that “tech entrepreneurs” are trying to solve: another dating, laundry, social, or local app?

Diversity is important. Just like in genetics, variation is necessary for survival. From a technology perspective: If we all thought the same, we wouldn’t think of anything new or different. Remember, it took a designer to disrupt hospitality (Airbnb) and a computer programmer to disrupt newspapers (Craigslist).

But it wasn’t until stumbling around in the startup realm, that I emerged as a changed person with a higher respect for diversity. Here’s why diversity matters:

Seeing things differently

If you’ve known something to be the the same year after year, it’s hard to think about it in different way.

- Investor Peter Thiel’s thesis is that a 20-year-old kid that has never relied on a programmed TV, post office, or recorded media will come up with the next big thing.

- Amazon saw retail, a model that ebbed and flowed and relied heavily on fourth quarter sales as a SaaS (software as a service) business, with recurring revenue by introducing Prime.

- Likewise, Innocentive, a crowdsourcing site for life science problems, saw that its most challenging problems were not solved by “experts” in a given field, rather they are solved by scientists in an adjacent discipline.

In fact, one of the caveats for successful crowdsourcing is diversity (along with independence, decentralization, and an easy way to collect data) as author James Surowiecki mentions in The Wisdom of Crowds.

Doing things differently

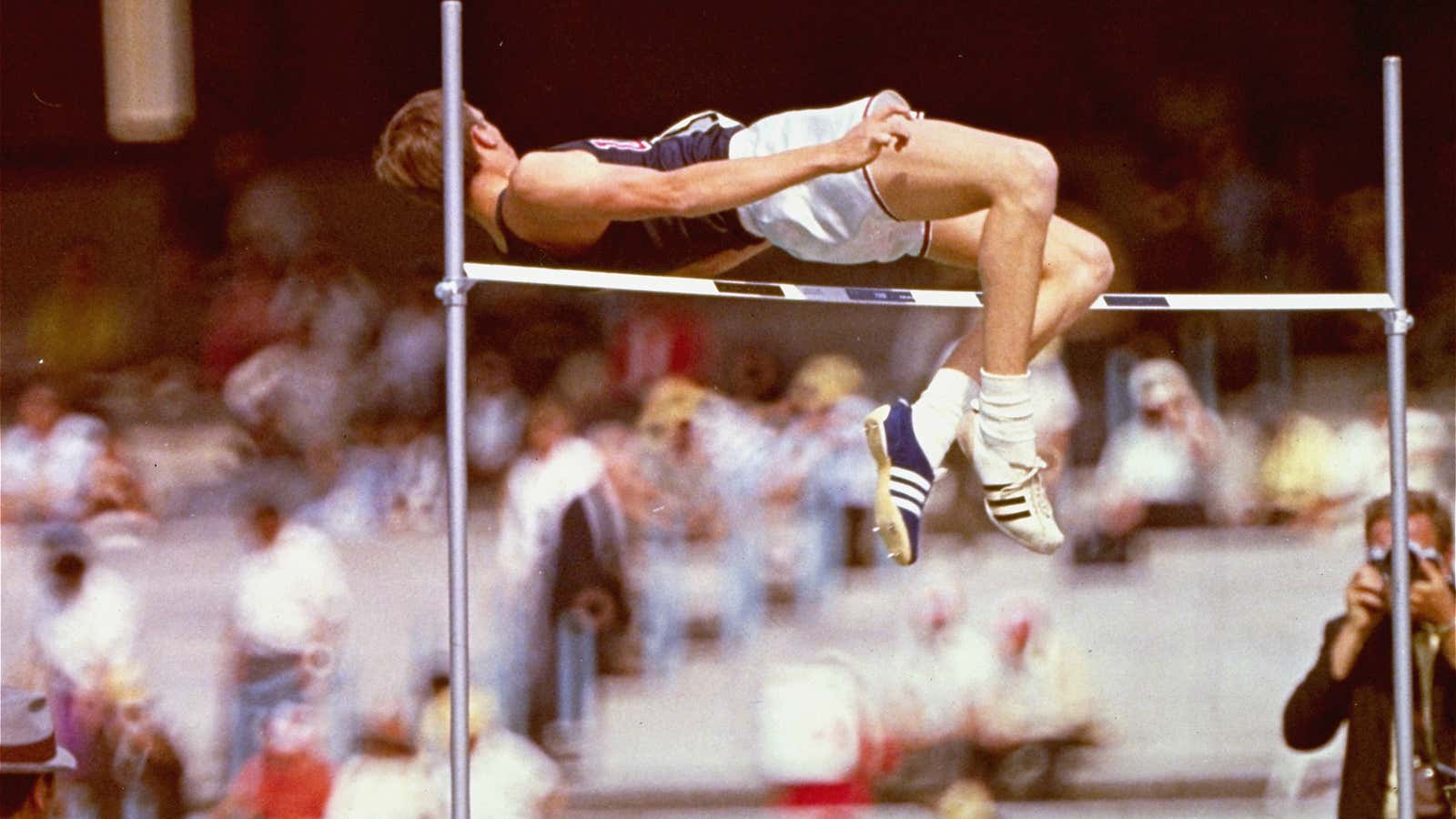

- High school coaches looked aghast at Dick Fosbury who was too uncoordinated to do the age-old dominant way of high jumping: the scissor kick. Coaches tried to change his technique, but in the end, the results for his head-first, lead-with-the-back, end-on-your-back method spoke for themselves. Today, the Fosbury Flop is the only way to perform the high jump.

- Similarly, but in a different era, all workers used to build products from beginning to end. This was highly costly as each worker needed the special skills required throughout all steps of the process as well as the mental switching costs from one skill to another. This led to lower output and quality control issues. Henry Ford thought that with division of labor and the introduction of the assembly line, he could increase efficiencies and lower the costs of labor; he thought correctly.

Thinking differently

- Face time used to be the key indicator of hard work in corporate America. However, companies like Best Buy see workers not as laborers but as thinkers, and as long as they can get their work done, they have unlimited vacation time. Its reduced work hours has led to higher efficiency, better retainment, and happier workers.

- Andrew Cohen from Brainscape goes a step further by allocating an outsourcing allowance to each employee. His mandate is to “outsource your own position” since it is the higher-level thoughts and ideas that drive value to the organization and not mundane button pressing.

- Alan Turing knew that machines could do a lot of the manual process that humans could, but much faster and without error. While he could not get his machine to actually crack Germany’s code during WWII, it weeded out the possibilities that were wrong. His team of cryptographers had a limited set of ciphers to examine instead of a near infinite number. His style of man working with machine is employed by PayPal, Palantir, and credit card fraud detection systems.

Even if a differing opinion is wrong, it helps the other parties think a bit more critically about the problem. Research has shown that “the decisions of a group as a whole are more thoughtful and creative when there is minority dissent than when it is absent.” It’s sometimes this lack of dissenting opinion, or groupthink, that leads to bubbles: from tulips to emerging markets to technology to real estate.

This brings us back to our original question of why all of the innovation in Silicon Valley seems so similar. Venture capitalists, who typically invest in what they know, extend 5-10% of funds to women, while crowdfunding, a more diverse method of raising money, allocates 47% of money to women, according to IndieGoGo’s CEO Slava Rubin. The US, since its inception, has led in the technology forefront because of its melting pot characteristics.

So is diversity the key to everlasting innovation?

It’s hard to know but the issues above may outline the advantages to having diverse teams in startups as well as large corporations. And if history is any indicator, the early adopters and technologists have started to push diversity initiatives. There are many programs that identify candidates based on race (Code2040, Black Founders, or Black Girls Code), gender (Women 2.0, Women Who Code, or Geekettes), and sexual orientation (StartOut, Lesbians Who Tech, TransHack).

Perhaps the next life-changing company will come from someone unexpected. Did anyone expect an acid-tripping, fruit-eating, Dylan-listening, hippie to change the world out of his parent’s garage? To be able to see different, think different, and do things different, have a team that is different—you don’t know the things that you don’t know, but your team might.