Redefining rigour: using stories to evaluate systems change?

.@CPI_foundation Australia & New Zealand hosted a global conversation around the concept of rigour, and doing rigorous work in complexity. Read @keira_lowther's summary of key insights

Share articleWant to work with @CPI_foundation Australia & New Zealand to explore what rigour might look like in complexity, and how you could be reflective, inclusive, brave in your work? Get in touch!

Share article"If we are to do rigorous work, we must consider where power lies. We must begin the process with openness, honesty, and a learning mindset." @keira_lowther reflects on a conversation around rigour.

Share articleWe put our vision for government into practice through learning partner projects that align with our values and help reimagine government so that it works for everyone.

I want to do good work. At the Centre for Public Impact Australia and New Zealand (CPI ANZ), I am reimagining government with colleagues who also want to do good work. It feels important that we have a shared sense that we are doing good work.

At CPI ANZ, we love ideas. Throwing an idea out on Twitter and seeing who else is grappling with it is a delight. In this case, my colleague Thea shared some ideas around the concept of rigorous work, and the response was enthusiastic and curious. Some tweets and a blog later, we found ourselves managing a growing list of people from around the world working in government, academia, and the arts who wanted to discuss the concept of rigour and how we might know whether we are doing rigorous work in complexity. In response, we hosted conversations in three different time zones to explore this further.

"We found ourselves managing a growing list of people from around the world working in government, academia, and the arts who wanted to discuss the concept of rigour."

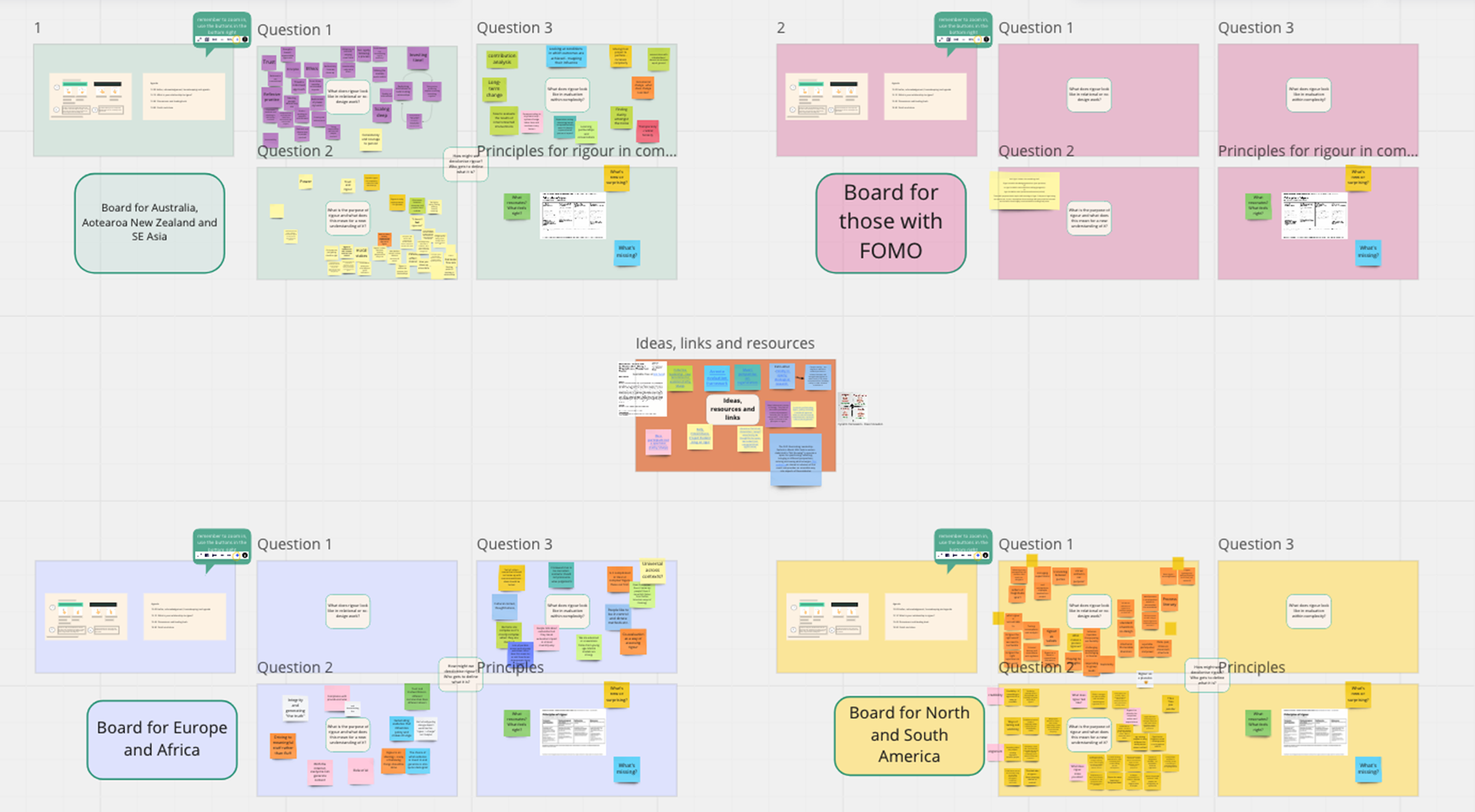

We created a Miro board (which remains open as a resource) that contained frames for each conversation and collected resources along the way.

The Miro board showing frames from each conversation; one for those who might not have made it, and a frame to collect resources that were mentioned.

The Miro board showing frames from each conversation; one for those who might not have made it, and a frame to collect resources that were mentioned.

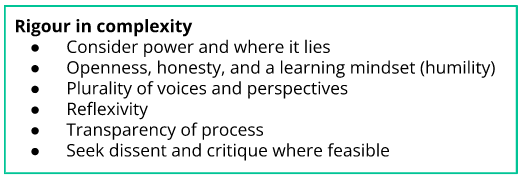

We also included principles of rigour shared by Penny Hagen, Kate McKegg, and Chris Vanstone at the Design and Evaluation for Impact conference in 2019.

Through the process, we shared our experiences with rigour. We heard how traditional conceptions of rigour are not a helpful fit for people working in complex environments. This discomfort is exacerbated for those trained in the sciences, who are keen to do good work but cannot fit the square peg of traditional concepts of rigour into the round hole of work in complexity. Others expressed guilt at not living up to the rigorous standards they had been trained in, and frustration at the disconnect and the insistence from those far from their work to comply with what was traditionally seen as a rigorous approach. But what else can we offer?

It was a huge privilege to host and listen to the courageous and creative conversations people were having. We heard interesting points that others, who have similar experiences with rigour, might find useful.

The purpose of rigour is to convey to others and ourselves that our work is good in terms of reliability and credibility. A rigorous process is one that creates work that meets these standards so that the work can be used to make decisions and change practice. It is important not to confuse the process with the outcome - rigour should be focused on the process that creates the outcome.

Traditionally, rigour is aligned with objectivity and defined by external authorities (such as academics). In practice, this looks like asking people to evidence their work in certain ways (for example, preferring numerical rather than narrative, even though both data sources are equally subject to bias). It looks like the pressure to enter into a randomised controlled trial when that might not be the best evaluation, or asking people to respond to questions determined by those who may not fully understand their experience.

When these practices and processes for objectivity are not a good fit and would not contribute to the quality of the work, others are needed, often created by those who need them. Processes created by those internal to the work are seen as subjective, and therefore less trustworthy and credible by those used to a more traditional approach.

In short, trust and credibility, and therefore rigour, are closely associated with perceived objectivity. External bodies are deemed more objective, and therefore are identified as the best people to determine rigorous work.

Who is trustworthy, and who has credibility? These questions bring the concept of power firmly centre stage. Those whom practitioners and managers are accountable to often hold more positional power (for example, funders, trustees, etc.), and those with positional power often prefer to listen to those with similar levels of power. These might be those with expert power (often academics who also hold institutional power) who share their expertise about what good looks like.

This is problematic in complexity because definitions of ‘good’ are often context-dependent. Therefore, the outside expert has less relevant insight compared with one who knows the context well - an inside expert. Those close to the action are often better placed to speak to the nuance of the situation, but the unspoken question from those in role power is often “can they be trusted?”.

This question contains classism and racism when those in power belong to the dominant culture. The recognition of this led the conversations towards the idea of decolonising rigour. This would mean moving from a definition held by external experts, to one that was meaningful to those who held the most risk (often community members). This would involve giving more credibility to those with cultural power, which seems to be often less valued or understood.

"Who is trustworthy, and who has credibility? These questions bring the concept of power firmly centre stage."

In our conversations, the impact of context on how value is determined (what rigorous processes look like) was clear. When working with those with role power who preferred a traditional approach to rigour, some described traditionally rigorous processes as a placebo - essentially ineffective (sometimes destructive) but calming and reassuring for those who wanted to see it. The traditional process creates a sense of trust and credibility that may be unearned for the context of complexity. Participants expressed a disconnect to the concept of rigour.

“Rigour wants something of me that I can’t give it and it can’t quite give me.”

On the Miro board, a participant has written 'rigour as placebo' and included a mind-blowing emoji.

On the Miro board, a participant has written 'rigour as placebo' and included a mind-blowing emoji.

For some, this exercise was seen as a way of narrowing down the pool of what kinds of knowledge or ways of knowing are worthwhile - which often led to excluding Indigenous ways of knowing. It led to a conversation exploring the controversial concept of “felt rigour”, where some expressed that when something is rigorous, you can feel it. It’s not easy to define, but you know when it’s not there. The question we were left with was - is this enough? Responses were mixed.

After listening to these conversations, I feel that if we are to do rigorous work, we must consider where power lies. We must begin the process with openness, honesty, and a learning mindset. Once this is established, we must openly discuss who is best placed to determine what good looks like. This might reveal racism or classism. We must face these prejudices and mitigate their impact on the work and those we are prejudiced against.

Drawing from the work of Kate McKegg, we must collectively create a framework for defining “good” and how it might be achieved. A plurality of perspectives seems important in this, as does reflexivity and transparency of process. We need humility to learn from dissent and critique. This might lead to taking a more mixed methods approach or incorporating storytelling to sit alongside quantitative statistics. By applying these principles (which are remarkably similar to those shared by Penny Hagen, Chris Vanstone and Kate McKegg in 2019) to our work, I feel confident that our processes and therefore outcomes will be trustworthy, credible, and rigorous.

We want to incorporate these reflective, inclusive, transparent ways of defining quality into our approaches to what a learning partner looks like.

If you’d like to work with us, please get in touch, so we can try to be reflective, inclusive, open, and brave together.