Dear pathology company, your knowledge management failures have caused serious harm

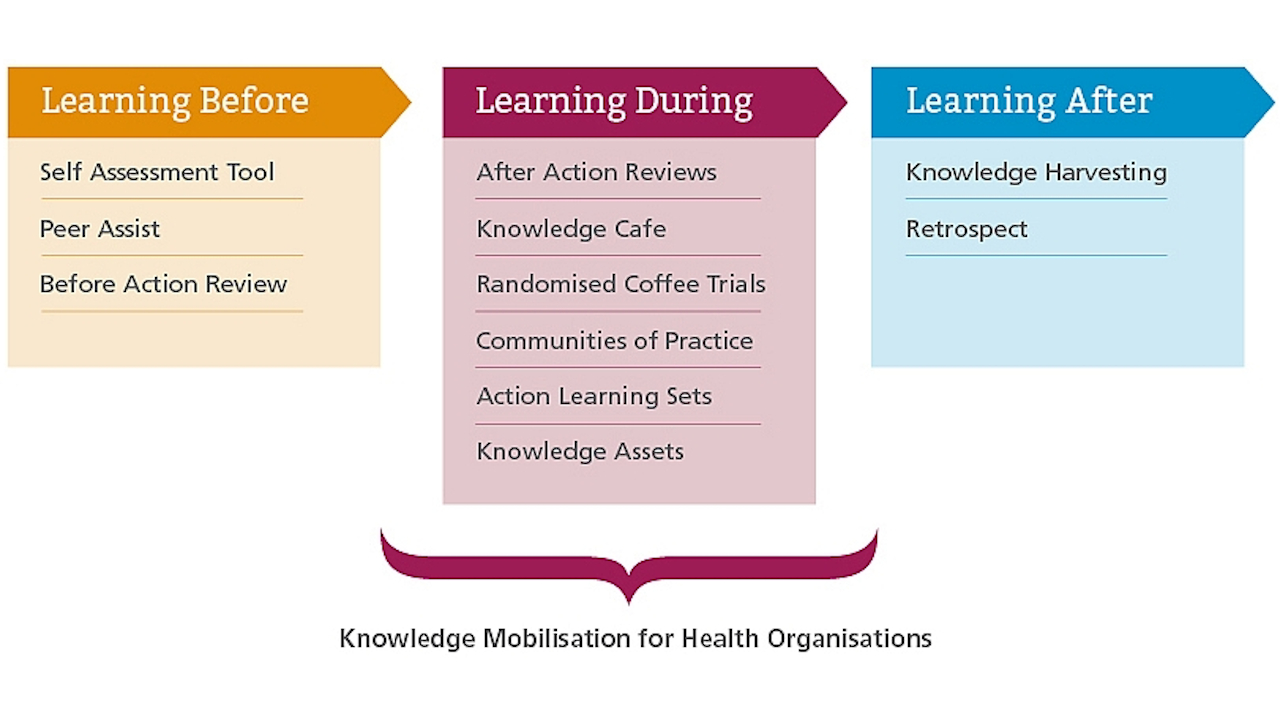

A knowledge management (KM) colleague recently disagreed with the use of the word “failures” in a RealKM Magazine article. My colleague argued that research looking at the language used in lessons capture had highlighted the benefits of not using wording such as “failures” or “negative lessons.” He advised that using positive wording such as “need for improvement” dramatically changed the outcome of the lessons process in a positive way.

Although the use of the word “failures” was actually appropriate in the context of the particular article, I very much agreed with my colleague’s view.

However, a set of personal experiences last week has made me acutely aware that the emotional needs of the people in an organization conducting lessons capture is only part of the consideration. The emotional needs of the people outside the organization who are affected by the matter that is the subject of the lesson capture – that is, clients or stakeholders – also need to be considered.

If those clients or stakeholders have been seriously harmed by the matter in question, then they may well feel that “failure” is the only appropriate word to use, and that the use of more positive language is an abrogation of responsibility by the organization.

That’s why you’ll see “failure” in both the title of this article and the saga below, and hopefully after reading the saga and the correspondence it includes you will understand the reasons for this.

However, to provide those responsible with the best possible opportunity to hopefully learn from what has happened without blame or shame, I have anonymized both the organization and its members, for now at least.

Experiential knowledge failure

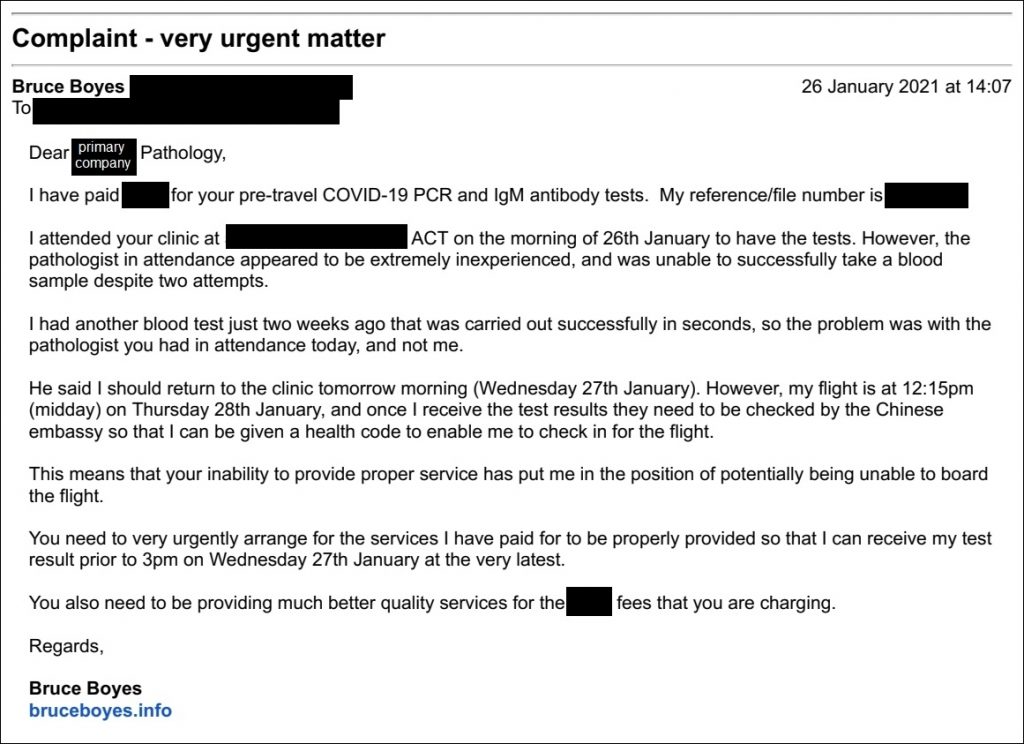

The saga began last Tuesday 26th of January, ahead of an international flight to China scheduled for last Thursday, the 28th of January.

As with a growing number of countries, the Chinese Government very responsibly and sensibly requires people traveling to China to provide negative COVID-19 test results before being allowed to board their flight. Both nucleic acid and IgM antibody tests are required, and they must be conducted within two days before boarding. The nucleic acid test, for those who haven’t yet had one, involves throat and nostril swabs and then the subsequent laboratory analysis of these samples. The IgM antibody test involves extracting a small amount of blood and then the subsequent laboratory analysis of this sample. After negative test results are received, they are then submitted online, and following examination and verification by the Chinese Embassy or Consulate-Generals, a green QR code is issued.

Free and widely available nucleic acid testing can be accessed by those experiencing symptoms of COVID-19 or who are otherwise required or encouraged to undergo testing, for example because they are a close contact of a confirmed case. However, pre-travel COVID-19 testing is carried out only at a limited number of pathology clinics, and involves a fee of a couple of hundred dollars.

Although Tuesday 26th of January was a public holiday in Australia (for Australia Day), I had checked carefully before booking the flight to make sure that the only designated Canberra COVID-19 pre-travel pathology clinic would be open on that day. This is because I couldn’t do the tests on Monday 25th of January as that would have been outside the two-day limit, and I was concerned that if I had the tests on Wednesday 27th of January then I may not receive the results in time to be able to then receive the green QR code in time for boarding on the morning of Thursday 28th of January.

This is particularly the case because of the delay in carrying out sample analysis after samples are taken. The Canberra pre-travel COVID-19 pathology clinic opens only in the mornings, and then after the morning testing session, everyone’s samples are sent together to the pathology company’s Sydney laboratory for analysis. Sydney is at least a three-hour journey from Canberra, and then the samples are placed in a queue for analysis. and then the analysis itself takes time. I knew from a previously unsuccessful travel attempt two weeks prior that testing on the morning of one day meant receiving the negative results in the early hours of the following morning, and then receiving the green QR code later that morning towards lunchtime (note that this previous travel attempt had been unsuccessful for reasons unrelated to COVID-19 testing).

However, when I went to the pathology clinic for my COVID-19 tests on Tuesday 26th of January, I was confronted with the situation in my complaint email in Figure 1. I couldn’t believe what was happening given that I’d successfully had blood extracted by a different pathologist for the same test at the same clinic just two weeks previously, with the procedure taking only seconds. It’s a common and standard blood extraction procedure that would be carried out thousands of times daily across the world, and that I’ve experienced numerous times in my life. This includes annual medical checks in China where several vials of blood are extracted at once for wide ranging health assessments. Never before have I encountered the situation where the medical practitioner couldn’t extract even one drop of blood.

The pathologist who was working at the clinic on Tuesday 26th of January appeared to lack the experiential knowledge needed to be able to deliver the required services with a high degree of certainty in what was a time-critical situation. I consider this to be a very serious knowledge management failure on the part of the pathology company.

When I confronted the pathology company about this, they said that Tuesday 26th of January’s pathologist had only around six months of experience, and then afterwards different people in the company expressed different views in regard to the implications of his experience level. The diversity of views suggests the lack of a coherent approach by the company to this time-critical testing.

The pathologist who was at the clinic the following day, on Wednesday 27th of January, said that Tuesday’s pathologist wouldn’t again be used for this particular testing, which I considered to be a very appropriate response. However, others from the company indicated that they thought that having a diversity of experience and skills available in this situation was perfectly fine. There may be some benefits in this (not being a pathologist I’m not sure what), but surely a much higher priority for the company should be the delivery of time-critical services to fee-paying customers with the maximum possible degree of certainty.

Failure to access and use client knowledge and understand the context

The only option I then had available was to go back on Wednesday 27th of January for another attempt at having the samples taken, in the hope that I could receive the analysis results and green QR code in time. I did this, and as had been the case two weeks previously, the blood extraction was carried out successfully in seconds, further confirming my arguments above. The pathologist said that I had “good veins” so blood extraction was straightforward.

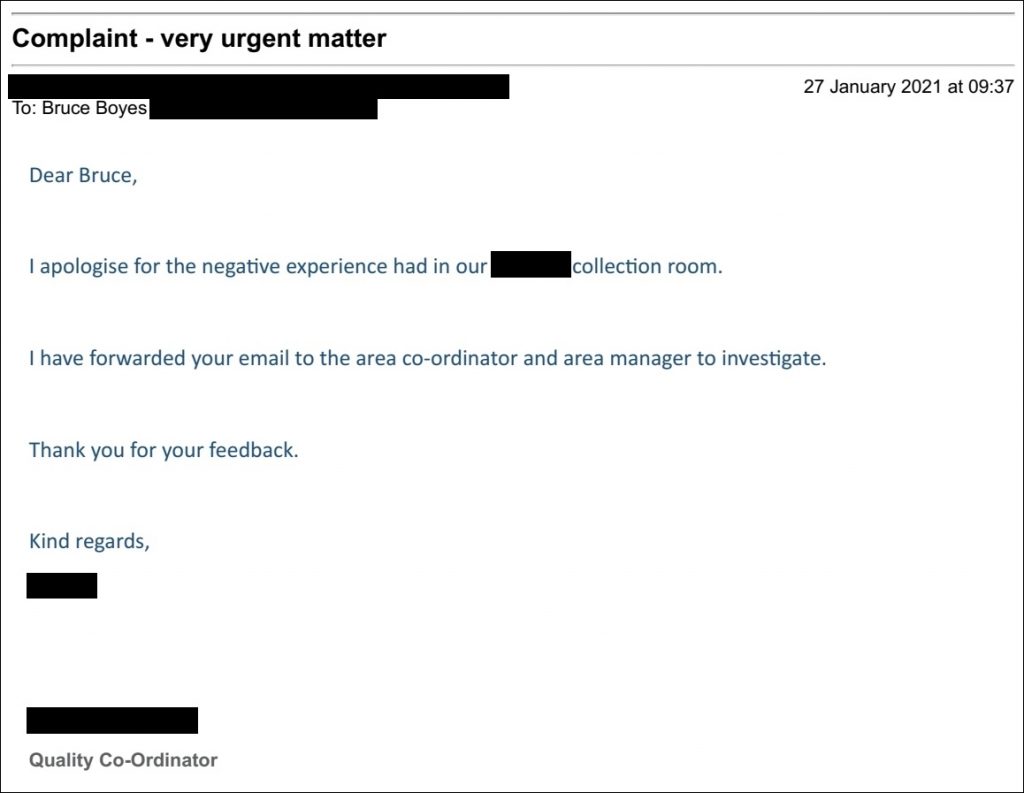

This second sample taking coincided with the pathology company making contact in regard to my complaint in Figure 1, as shown in Figure 2 below and the very first SMS message in Figure 3. When I made telephone contact with the company representatives, I strongly stressed the urgency of receiving the test results, particularly given the company’s failure to successfully deliver the testing services the day before.

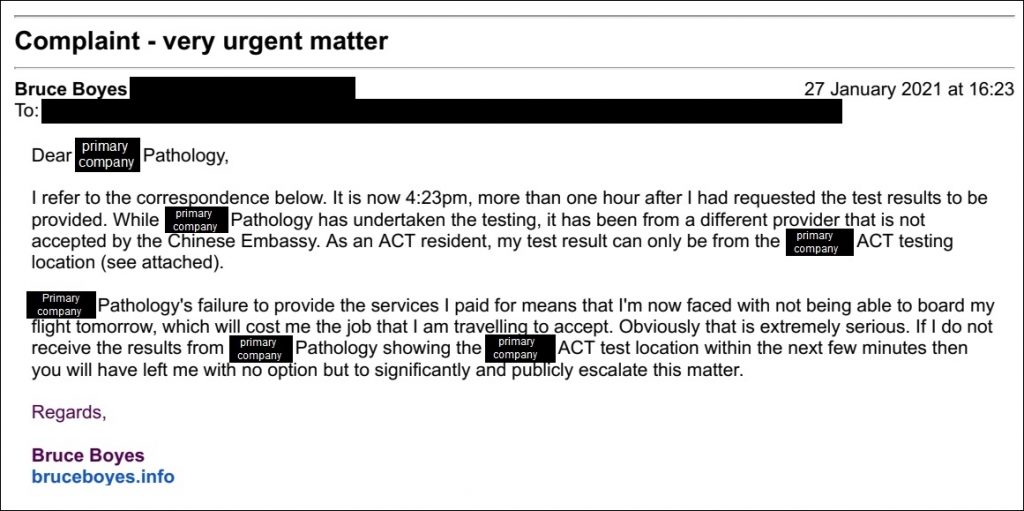

However, later in the afternoon, I would find myself stunned by the emergence of further knowledge management failures.

Because I needed it urgently, the pathology company sent my samples to another pathology company in Canberra and tasked them with doing the analysis, instead of sending it to their own laboratory in Sydney as normal. But they did this without asking me at all, and I was horrified when I found out because very understandably only reports from the designated travel testing pathology company are accepted by the Chinese Embassy or Consulate-Generals.

The emergence of this problem and what then happened afterwards are shown in Figures 3 and 4 below. What I call “primary company” pathology is the company that operates the designated Canberra pre-travel COVID-19 pathology clinic where I had my samples taken. What I call “secondary company” pathology is the other Canberra pathology company where the primary company decided to send my samples without consultation with me, as discussed in the paragraph immediately above.

As shown in Figures 3 and 4, the primary pathology company still ended up having to send my samples to Sydney through the night for re-analysis in their own laboratory, which ended up making the whole process slower than it would have been if they had just sent them to Sydney in the first place.

When I finally received the green QR code later in the morning of Thursday 28th of January it was too late to be able to successfully take the flight. The secondary pathology company has also advised that I will be billed for their analysis that I did not request and which could not be used.

The primary pathology company should have consulted me before sending my samples to the secondary company for analysis. Accessing and using client knowledge should be essential before making any such decisions. That the primary pathology company sent my samples to a secondary company also revealed an inadequate understanding of the context in which their pre-travel testing is conducted. I consider these to be further very serious knowledge management failures on the part of the pathology company.

My Chinese visa expired on the 29th of January, and new visas are not currently being issued due to China implementing necessary COVID-19 travel precautions ahead of the Spring Festival period. This means that I’m now in very insecure and uncertain territory, with my work and life in China at great risk after what has already been a difficult year.

This is the serious harm caused by knowledge management failures.

Header image source: Mufid Majnun on Unsplash.

Great piece. Loved the explanation on experiental knowledge, it is very clear.

What an omnishambles! Very sorry to hear about this, Bruce.