Taking responsibility for complexity (section 3.1.1): Decentralisation and autonomy

This article is part of section 3.1 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems.

Especially with complex problems, there is too often a mismatch between the scale of what is known about the world and the level at which decisions are made and actions taken1. One way of enabling lower levels and smaller scales is decentralising policy-making and implementation. Attention should be paid to the scales at which different aspects of a problem are best perceived, and where the incentives (and the potential for collective action) lie for addressing it in a sustainable manner.

Having decisions made close to those most affected is a way to provide better and quicker feedback and ensure decision-makers are well-informed about problems, the effects of (proposed) interventions and the nature of different interests2. A central finding of the literature on adaptive governance is that the devolution of responsibilities, rights and access to resources to local management bodies can contribute to addressing complex policy problems and local adaptive management, by 1) better capitalising on local understandings of a resource or locality (devolution of management rights and power sharing promotes participation3; and 2) promoting innovation and experimental learning, stronger internal enforcement of rules and decisions (through mutual observation and social incentives) and improved higher-scale risk management through local redundancy4. These insights, developed primarily by looking at CPR [common pool resources] management, are nonetheless relevant for a very wide set of imperfectly excludable resources5.

This is not simply about giving as much power as possible to the lowest level possible; there needs to be an assessment of the best levels of decision-making authority for different aspects of a problem, and at what level to build collective action and institutional coordination. For example, research on institutional ‘fit’ shows that jurisdictional boundaries of governing bodies for ecosystems should coincide with ecosystems’ limits (e.g. river basin management), nested and interacting at various scales. For example, CPR users, closely connected to the system, are in a better position to adapt and shape ecosystem change than remote levels of governance, and those with a long-term stake in sustainability are more effective at managing such resources6.

Distributing power for and involvement in decision-making throughout an organisation can be done in a number of ways. Lessons can be drawn from public sector models but also private sector experiences with ‘the network organisation’ 7 and ‘network-centric organisations’ 8. This involves granting considerable individual autonomy and integrating various channels for participation in key decision-making processes, and has improved cost-effectiveness, timeliness and productivity in some contexts9. Alternatively, ‘Total Quality Management’ principles adopted in manufacturing and service industries, in the private and then public sectors, casts the ‘quality’ of a product or service as the responsibility of all employees. This is implemented by empowering employees with mechanisms for solving problems and improving performance distributed across a variety of levels rather than simply the domain of supervisors or inspectors10.

Incorporating this within the accountability frameworks of an agency or ministry could revolve around granting an ‘earned autonomy.’ Certain benchmarks for performance are set, along with minimum requirements for programmes to achieve in order to prove their competency. Units are then allowed freedom to make decisions on a variety of matters, such as programme priorities, reporting structures and processes and staffing. In this situation, a centrally given policy would look to ‘establish the direction of change, set boundaries not to be crossed, allocate resources and grant permissions where units can exercise innovation and choice’ 11.

Next part (section 3.1.2): Engaging local institutions and anchoring interventions.

See also these related series:

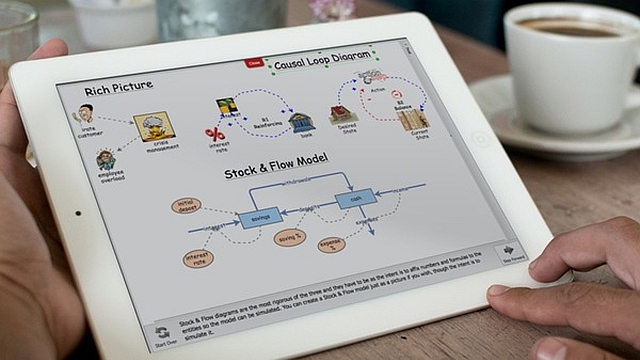

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity.

Article source: Jones, H. (2011). Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems. Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Working Paper 330. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/6485.pdf). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

References and notes:

- This is seen in the dual problem of large-scale scientific knowledge that has little relevance to local decision-makers (e.g. global climate models that are at a resolution that is not useful to sub-national decision-making), and local, tacit or indigenous knowledge that is not seen as credible by national or international actors (e.g. artisanal fishing knowledge that is not taken into account in international treaties on fisheries). The general result is the production of scientific and technical information that lacks salience, credibility or legitimacy in the eyes of critical players at different levels. Cash, D., Clark, W., Alcock, F., Dickson, N., Eckley, N., Guston, D., Jager, J. and Mitchell, R. (2003). ‘Knowledge Systems for Sustainable Development’, The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100(14): 8086–91. ↩

- Swanson, D. and Bhadwal, S. (eds) (2009). Creating Adaptive Policies: A Guide for Policy Making in an Uncertain World. Winnipeg and Ottawa: IISD and IDRC. ↩

- Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P. and Norberg, J. (2005). ‘Adaptive Governance of Socio-ecological Systems.’ Annual Review of Environment and Resources 30: 441-473. ↩

- Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ↩

- Hatfield-Dodds, S., Nelson, R., & Cook, D. C. (2007). Adaptive Governance: An Introduction and Implications for Public Policy (No. 10440). Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society. ↩

- Swanson, D. and Bhadwal, S. (eds) (2009). Creating Adaptive Policies: A Guide for Policy Making in an Uncertain World. Winnipeg and Ottawa: IISD and IDRC. ↩

- Miles, R. and Snow, C. (1986). ‘Organizations: new concepts for new forms’, California Management Review 28(2): 68-73. ↩

- van Alstyne, M. (1997). ‘The State of Network Organization: A Survey in Three Frameworks.’ Journal of Organizational Computing 7(3): 88-151. ↩

- Heller, F., Pusic, E., Strauss, G. and Wilpert, B. (1998). Organizational Participation: Myth and Reality. New York: Oxford University Press. ↩

- Reid, D. and Sanders, N. (2007). Operations Management: an Integrated Approach (3rd Edition), John Wiley and Sons. ↩

- Chapman, J. (2004). System Failure: Why Governments Must Learn to Think Differently. London: DEMOS. ↩