What we do (and don’t) know about the factors linked to workplace coaching success

Originally published in ScienceForWork.

Key points

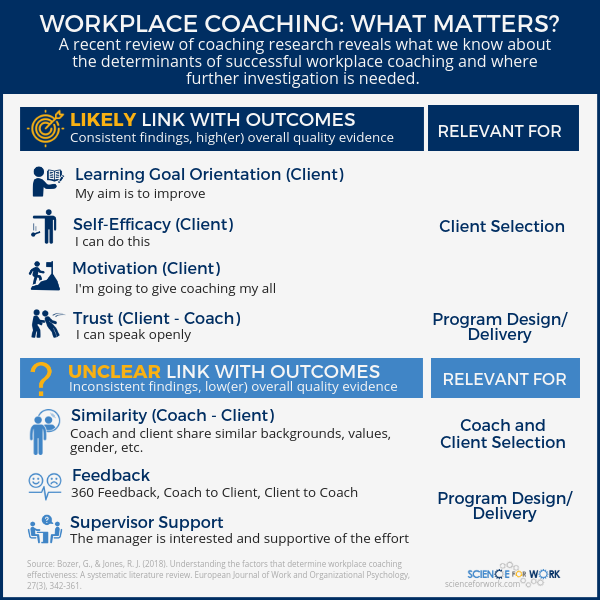

- Coach-client trust, coaching motivation, and client self-efficacy are most consistently linked with workplace coaching success in current empirical research on coaching.

- The influence of feedback, coach-client similarity, and supervisor support is less clear.

- In addition to external research, people designing workplace coaching programs may want to look to organizational sources of evidence to inform their efforts.

We know that workplace coaching is linked to positive outcomes, such as improved performance. That’s good news considering that organizational spending on coaching is going nowhere but up1 2. Yet, knowing that positive results from coaching are possible isn’t sufficient. We should also aim to understand the aspects of coaching that are likely to lead to such success.

Taking a deeper look into the factors linked with workplace coaching success

In their 2018 systematic literature review3, Gil Bozer and Rebecca Jones sought to uncover which aspects of workplace coaching – defined as one-on-one coaching in an organizational setting – make the most difference to coaching outcomes. They did this by reviewing both the findings and overall quality of evidence in 117 studies. They defined quality based on five factors (e.g., study design, consistency of findings, etc.)

Note, the aspects of coaching reviewed in the study are not necessarily the “most important,” but rather those for which enough research existed to enable a review.

Coaching success starts with client characteristics

People who are interested in learning and improving (versus showing what they already know or who see their abilities as fixed) are more likely to see improved job performance as a result of coaching. People’s level of confidence in their abilities (self-efficacy), and motivation to participate in coaching also seem likely to make a difference.

Are employees who don’t display these characteristics a bad fit for coaching? Not necessarily. This research suggests that self-efficacy and coaching motivation may also be outcomes of the coaching process. In other words, clients may develop a stronger belief in their skills and a greater interest in working towards their goals as a result of being coached.

The coach-client connection matters, but only in some ways

During coaching, clients have the opportunity to speak candidly about their challenges. Whether they choose to do so, may have something to do with trust — usually defined as one’s openness to vulnerability. It’s no surprise, then, that there is pretty consistent evidence suggesting a link between client-coach trust and positive outcomes, such as the perceived effectiveness of coaching. One influential factor seems to be the client’s degree of trust that the coach will hold in confidence what is shared during coaching sessions.

Perhaps more unexpected are the inconsistent findings related to coach—client similarity. The researchers suggest the mixed findings may indicate that the importance of similarities in professional background, values, or interests decreases over the life of the coaching engagement. For instance, although a client could, at first, feel more at ease with a coach that is similar to her – I am a CFO and this coach was a CFO – as the relationship develops the relevance of such connections may decrease. The inconclusive evidence to date suggests that it may be more impactful to select coaches based on their skills as coaches, rather than their broader professional background or interests.

Findings about the influence of feedback and supervisor support may surprise you

Based on current empirical research, it’s not clear if feedback influences the effectiveness of coaching. However, there is evidence about feedback in general that indicates while it often improves performance, it also has the potential to decrease it4. As such, those managing workplace coaching efforts may want to take a fresh look at feedback in their programs, ensuring that its purpose is clear and those involved are skilled in facilitating, delivering, and receiving feedback.

Finally, considering that workplace coaching happens within a greater organizational context, it’s reasonable to wonder how important the support of a client’s manager is to the success of the effort. Some evidence suggests that those involved in coaching feel the supervisor’s support is important and that it may influence how clients perceive the value of coaching. Overall, though, the findings in this area is inconclusive. Practitioners may look to additional sources of evidence, such as professional experience, internal data from existing coaching programs, and stakeholder perspectives, to understand the link between supervisor support and coaching effectiveness in their organizations.

Takeaways for Your Practice

Current research provides insights that can inform various aspects of workplace coaching programs, such as:

- Client selection: Those who demonstrate a greater motivation to engage in coaching, are interested in acquiring new skills or perspectives, and are confident in their ability to develop them, may be the most likely to see benefits from coaching.

- Coach selection: The similarity of experiences, skills, and values between a client and coach may increase a client’s comfort initially. However, the importance of such qualities to coaching outcomes is not evident. Thus, it may be more relevant to select coaches based on their coaching expertise, rather than their experience in other areas.

- Feedback: Although feedback interventions (e.g., 360 feedback) in coaching are common, there is mixed evidence about feedback’s links with coaching outcomes. It may be wise to take a critical look at the role of feedback in your program, answering questions such as: What purpose is feedback intended to serve? How do we ensure coaches have the necessary skills to effectively facilitate the feedback process? How are clients prepared and supported to receive and respond productively to feedback?

- Confidentiality: Given the likely link between trust and coaching outcomes, particularly related to confidentiality, clarifying the information that will be shared outside the client-coach dyad seems essential. Seeking updates on the coaching process directly from the client, or in joint meetings with both the client and coach present, may also be a thoughtful approach.

Trustworthiness score

We critically evaluated the strength and quality of the study we used to inform this Evidence Summary. We found that the study design – a systematic literature review of mainly cross-sectional studies – is moderately appropriate to demonstrate a causal relationship. Therefore we can conclude that it is likely that the study’s findings do reflect determinants of workplace coaching success.

Learn how we critically appraise studies to assign them a Trustworthiness Score.

ScienceForWork

ScienceForWork is an independent, non-profit foundation of evidence-based practitioners who want to #MakeWorkBetter.

Our mission is to provide leaders and decision-makers with trustworthy and actionable insights from behavioural science.

Follow us on LinkedIn and Twitter to receive the most trustworthy scientific research summarized in less than 1000 words!

Did you like this Evidence Summary? Share it with your network!

Article source: The article What we do (and don’t) know about the factors linked to workplace coaching success is published by ScienceForWork under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

References:

- International Coaching Federation (ICF). (n.d.). 2016 Global Coaching Study. Retrieved from https://coachfederation.org/app/uploads/2017/12/2016ICFGlobalCoachingStudy_ExecutiveSummary-2.pdf. ↩

- Underhill, B.O. (2018). Executive Coaching 2022: Future Trends. Retrieved from https://coachfederation.org/blog/21025-2. ↩

- Bozer, G., & Jones, R. J. (2018). Understanding the factors that determine workplace coaching effectiveness: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(3), 342-361. ↩

- Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological bulletin, 119(2), 254. ↩