The Problem With WikiTribune

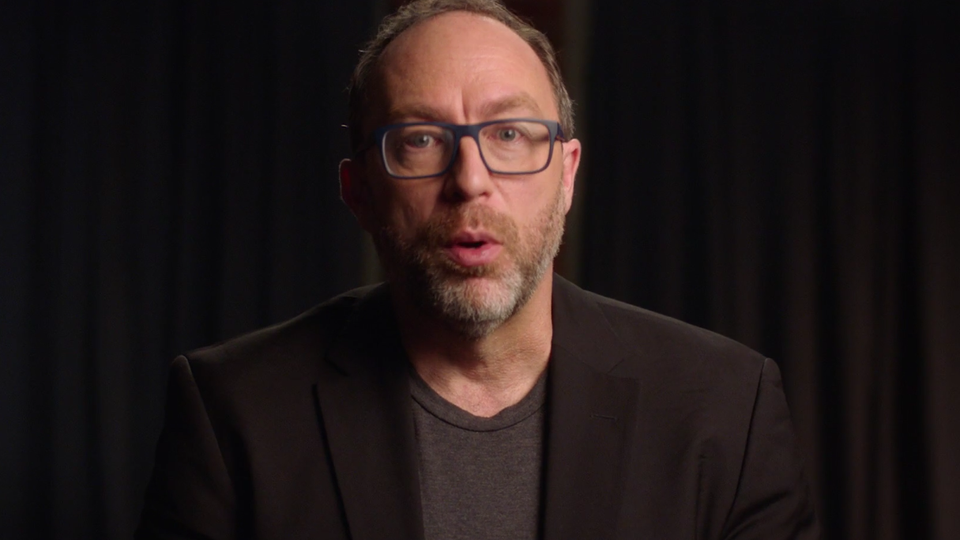

Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales’s new journalism site may be too ambitious for its own good.

Wikipedia has always seemed destined to converge with the news. An encyclopedia that is updated in real time is its own kind of news aggregator, after all.

And so it comes as no surprise that Jimmy Wales, the Wikipedia co-founder, is now launching a Wikipedia-like news organization called WikiTribune.

Wales explains the project on a new website, where he’s asking for donations so he can hire 10 full-time journalists. Those journalists will be tasked with reporting news stories that will then be fact-checked and edited by the wide world of internet volunteers.

“In most news sites, the community tends to hang at the bottom of articles in comments that serve little purpose,” WikiTribune says on its website. Instead, WikiTribune wants to have “professional journalists and community members working side by side as equals, and supported not primarily by advertisers, but by readers who care about good journalism enough to become monthly supporters.”

There’s good reason to be skeptical of this model, but it’s not because volunteers can’t be trusted to make accurate contributions to the news.

Wikipedia is a remarkable success story in this regard. It has had issues with accuracy, yes, but it remains a rich and reliable starting point for good information. Wikipedia articles require robust citations, meaning it’s typically straightforward for readers to see where information originates. (Understanding or vetting the quality of any given source, however, is another story.) And though WikiTribune isn’t affiliated with Wikipedia, it does share its ethos: Both are based in the idea that most people will act in good faith as stewards of informational environments.

The larger problem with WikiTribune is this: Someone who is paid for doing journalistic work cannot be considered “equals” with someone who is unpaid. And promoting the idea that core journalistic work should be done for free, by volunteers, is harmful to professional journalism. The difference between a professional and a hobbyist isn't always measurable in skill level, but it is quantifiable in time and other resources necessary to complete a job. This is especially true in journalism, where figuring out the answer to a question often requires stitching together several pieces of information from different sources—not just information sources but people who are willing to be questioned to clarify complicated ideas.

The project raises many other questions. For starters, what are WikiTribune subscribers actually paying for? It’s not yet clear what kinds of stories Wales’s 10-person team will cover other than “global news stories,” he told Nieman Lab. That’s an awfully broad focus for such a small team. (For comparison: The New York Times has about 1,300 newsroom staffers—reporters, editors, fact-checkers, copy editors, photographers, and so on.)

Wales’s interest, for now, seems to be on the mechanics of news production rather than the substance of it. “The news is broken,” he says in a video on the WikiTribune crowdfunding site, “but we figured out how to fix it.”

The broken part, Wales says, has three core components. First, professional journalists are no longer the gatekeepers for publishing and broadcasting news—meaning anyone can publish anything to the web, including on websites designed to profit from deception. Second, the business model supporting quality journalism is busted. Ad-based websites are engaged in a content-churning war for clicks that doesn’t always result in high-quality journalism—because news organizations need web traffic to attract advertisers, and they need advertisers to pay the salaries of journalists. And, third, many people aren’t willing to pay money to support quality journalism. All the while, people overwhelmingly get their news on platforms like Facebook, and Facebook’s algorithm shows its users things it knows they will like—regardless of whether those things are true. (Making matters worse for news organizations, Facebook is slurping up a huge portion of the ad dollars that news organizations are themselves after.)

Given all this, Wales says there’s a need for high-quality journalism that doesn’t rely on ads and that restores people’s trust in news by making them stakeholders in the quality of—in the very production of!—the information they’re seeking. “It’s a movement that we believe will eventually obliterate low-rent, unreliable news for good,” WikiTribune says on its site. This is an appealing outcome, but it’s not totally clear how WikiTribune will get us there.

Wales wants the news on his site to be a “living, evolving artifact,” he says, but one wonders how much time WikiTribune’s journalists will be expected to spend revising their past work. When an article is never truly finished—when a community of volunteers is constantly flagging a story for review, or adding new details, then debating those additions—at what point is the journalist free to move on to the next assignment? (WikiTribune didn’t immediately respond to my request for an interview.)

There’s a deeper question of authorship in all of this, too. At what point in the never-ending editing and rewriting process does an article cease to be by the person who originally wrote it? The answer to this question will have to be reflected in WikiTribune’s design. If the model is anything like Wikipedia’s page history, the level of transparency that is necessary can make it incredibly time-consuming for readers to synthesize the true source of what they’re reading.

Wales isn’t the first person to think about a Wikipedia-like model for the news. When the eBay founder Pierre Omidyar created Peer News, in 2010, it was conceived of as a “Wikipedia for the news.” Omidyar wanted to challenge the standard article format and remake stories to be reported and cited in web-native ways. I joined the fledgling organization as a city hall reporter shortly after its launch as Honolulu Civil Beat that year.

In addition to covering the news, reporters like me were tasked with writing and maintaining Wikipedia-like topic pages about people and things that appeared frequently in our reporting—pages that offered background about newsmakers like the mayor, or taxpayer-funded projects like Honolulu’s controversial plan for an elevated rail line, and linked back to our reporting. The idea was: Who better than professional journalists, the people closely and neutrally covering these topics, to describe them to our world of readers? In theory, it was brilliant. But for our small newsroom—which was, at the time, around the same size as what Wales is proposing for WikiTribune, keeping topic pages updated was a slog. It certainly didn’t happen in real time. We were busy reporting and breaking news.

Reflecting on this experience, I can see why the idea for a volunteer corps of people updating small details of evolving stories in real-time is appealing—but I can also see why it’s potentially problematic.

Imagine a WikiTribune reporter quotes a politician who decides, once he’s read the story, that he’d like to take back what he said. What’s stopping that politician from logging onto WikiTribune and revising the article himself? Even with mechanisms in place to flag such edits—perhaps WikiTribune’s full-time journalists will be tasked with reviewing edits to quotes before they’re made—how can WikiTribune readers be sure that the people making other, more nuanced kinds of suggested edits aren’t politically or financially motivated?

These are the kinds of questions professional journalists think about all the time when deciding who to interview, or what sources of information are reliable. They’re also the sorts of questions that confront Wikipedia’s editors.

If anything, perhaps WikiTribune’s greatest contribution to its readers won’t be the news it reports but the task of making readers think more like both journalists and Wiki editors. WikiTribune says on its website that it aims to infuse “professional, standards-based journalism” with “the radical idea from the world of Wiki that a community of volunteers can and will reliably protect and improve articles.” But seen another way, it is a crash course in media literacy.

The WikiTribune model—evidence-based, heavily cited, community kept—may work in theory. The best wikis are “communal gardens of data,” as the writer Steven Johnson put it in 2001, the year Wikipedia launched, wherein “some participants do a lot of heavy planting, while others prefer to pull a weed here and there.” Gardens can thrive this way. Or they can wilt and wither away. The reason the tragedy of the commons is so often evoked in conversations about digital environments is because we have abundant evidence of online communities that descend into chaos. Wikipedia, despite its many problems, is still a bright spot. It’s a truly astonishing example of what people can build together, bit by bit by bit.

So it’s tempting to imagine a new kind of journalism site that tidily solves so many of the industry’s problems—a site that’s indifferent to the shrinking pool of available ad dollars, that gets people to carefully vet the information they encounter on a massive scale, a site that inspires people to spend their money on quality journalism, and a site that consistently produces it. This is ambitious stuff. Maybe too ambitious.

After all, for WikiTribune to accomplish its goals, people will have to agree to both pay for the service and build it themselves—with most of them doing that work for free.