Report from ICWSM 2017 Workshop on Digital Misinformation

The current proliferation of fake news, conspiracy theories, and deceptive social bots is leading to a rising tide of misinformation. The consequences of this flood of misinformation include the manipulation of public opinion, the stoking of science denial, and greater information overload.

Recognising that countering misinformation while protecting freedom of speech requires collaboration across key sectors including industry, journalism, and academia, the Workshop on Digital Misinformation was held in conjunction with the 2017 International Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM) in Montreal, Canada on 15 May 2017.

The workshop brought together a range of researchers in this emerging area, as well as representatives from Facebook, Twitter, Google, Microsoft, Buzzfeed, and Snopes.com. It consisted of a series of “lightning talks” followed by interactive panels that identified 15 research challenges around three questions:

- How to define and detect misinformation?

- How to best study the cognitive, social, and technological biases that make us vulnerable to misinformation?

- What countermeasures are most feasible and effective and who can best deliver them?

The report from the workshop is now available, and is summarised below.

Lightning talks

Craig Silverman (Buzzfeed):

- Proposed a working definition of ‘fake news’ as “fabricated news intended to deceive with financial motive.”

- Emphasized the global scope of the issue.

- Advised that journalists are now aware of the scope of the problem and are reporting on fake news stories—though not always well.

- Called for more collaboration between journalists and academic researchers for the study of misinformation.

Leticia Bode, political scientist and communication scholar (Georgetown University):

- Certain topics (e.g. GMOs) are easier to correct than others (e.g. vaccines & autism).

- ‘Social’ fact checking is more effective if it links to credible sources.

- Recommended that news organizations emphasize easily linked references and that corrections should be early and repeated.

- A new partnership model with social media platforms could satisfy these requirements.

Áine Kerr, leader of global journalism partnerships (Facebook):

- The quality of links on Facebook’s News Feed varies dramatically.

- Facebook is seeking to amplify the good effects and mitigate the bad by (1) disrupting the financial incentives for fake news; (2) developing new products to curb the spread of fake news, such as allowing users or 3rd party fact checkers to flag posted stories as untrue or unverified; (3) helping people make informed decisions by educating them on how to spot fake news; and (4) launching the News Integrity Initiative, a partnership between industry and non-governmental organizations to promote media literacy.

- Facebook regularly engages with the research community via collaborative programs and grants.

Paul Resnick, computer scientist (University of Michigan):

- Factual corrections are often ineffective and slow; they rarely reach the people originally influenced by the misinformation.

- We are exposed to information filtered by socio-technical mechanisms that largely prioritize popularity over accuracy, such as search engines, upvotes, and newsfeeds.

- Argued that a more widespread adoption of reputation-based filtering technologies would lead to more accurate content being shared.

- Reported on his own work on gauging the trustworthiness of sources using a prediction market.

Rolf Fredheim, data scientist (NATO StratCom Center of Excellence):

- Discussed recent spate of misinformation operations in Europe and the problems created by the decreasing credibility of governments and the media in the eyes of the public.

- Noted that while governments want a quick fix to the problem, comprehensive approaches are required, including adjusting the incentives for news production and consumption as well as providing education and awareness of misinformation.

- Insisted that social media need to be considered seriously as a tool of soft power and thus social media companies should be pressured to police their platforms.

Panels on research challenges

How to define and detect misinformation?

Jisun An, computer scientist (Qatar Computing Research Institute) presenting on behalf of Meeyoung Cha, computer scientist (Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology):

- Misinformation can be defined as information unverified at the time of circulation and later determined to be false.

- Misinformation can be an economic threat.

- More theoretical work is necessary to understand why people spread rumors; this is less well understood than the incentives for creating rumors.

James Caverlee, computer scientist (Texas A&M University):

- Statistical approaches to detecting misinformation require labeled instances to train machine learning models.

- Aggregated signals could be exploited to infer the reliability of a given piece of content, such as the Reply to Retweet ratio to flag controversy.

- Crowdsourced information can be easily manipulated, for example it is easy to recruit workers for astroturfing.

- More research is needed on the problem of identifying the intent behind social media posts, which could lead to tools for distinguishing organic conversations from covert coordinated campaigns.

Qiaozhu Mei, computer scientist (University of Michigan):

- Hacked accounts can bypass reputation systems.

- While spotting known rumors is easy after the fact, identifying (false) rumors in their early stages is difficult.

- Proposed a four-part approach: (1) identifying emerging rumors early by mining search engine logs for questions about a statement’s truthfulness; (2) retrieving all the posts about a rumor; (3) analyzing the impact of a rumor and its correction via visualization; and (4) predicting its future spread through deep learning.

Eni Mustafaraj, computer scientist (Wellesley College):

- Discussed an early example of fake news tactics, where a group of Twitter bots utilized hashtags targeted towards specific communities in a coordinated campaign to spread negative information about a US Senate candidate.

- Compared this attack with recent ones, leveraging fake Facebook accounts to target specific Facebook groups and spread links to fake news stories.

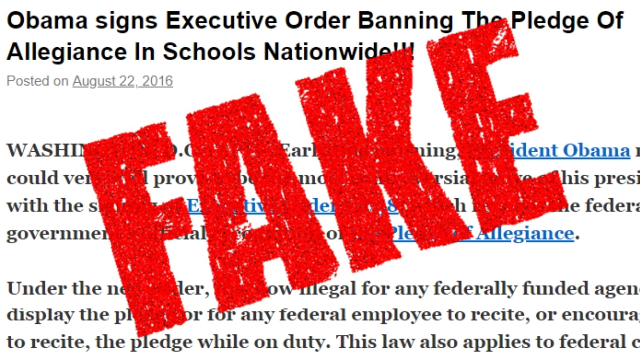

- Discussed seven categories of mis- and disinformation proposed by First Draft News (satire, misleading thumbnails/titles, misleading content, information in false contexts, outright impersonation of sources, manipulated content, and entirely fabricated content).

- Examined three motives for spreading such inaccurate information: financial, political, and ideological/cultural (including prejudices like sexism and xenophobia).

- Proposed that social media platforms should highlight provenance information about sources to help users determine their intents and trustworthiness.

- Urged platforms to provide researchers with data about how recipients of misinformation engage with it.

Kate Starbird, information scientist (University of Washington):

- Delineated different types of rumor in a crisis situation, such as hoaxes, collective sense-making, and conspiracy theories.

- Categorized methods for detecting misinformation based on linguistic, network, account, URL domain, and crowdsourced features.

How to best study the cognitive, social, and technological biases that make us vulnerable to misinformation?

Joel Breakstone, historian (Stanford University):

- Cited a study showing that students have difficulty distinguishing the reliability of news stories. Assessments of validity were found to rely primarily on the appearance of the article rather than on consideration of the source, and 80% of the time students were unable to distinguish native advertising from real news stories.

- The fight against misinformation is one in which we all must take part, not just big tech companies.

R. Kelly Garrett, communication scholar (Ohio State University):

- Distinguished between holding a belief and being ignorant of the evidence against it, citing statistics on the number of people who know the scientific consensus on global warming but reject it.

- But noted that online partisan news lead people to reject evidence, due to these outlets’ emotional pull.

- While social media increase the profile of misinformation, it remains unclear how much this actually shifts public opinions.

Kristina Lerman, physicist (University of Southern California):

- Emphasized that human limits of information processing make it impossible to keep up with the growing volume of information, resulting in reliance on simple cognitive heuristics to manage the load. These heuristics may in turn amplify certain cognitive biases.

- Has been researching position bias, which is the idea that people pay more attention to what is at the top of a list or screen. Experimental trials show that news stories at the top of a list are 4-5 times more likely to be shared.

- Social media reinforce network biases, creating echo chambers that distort our perceptions.

David Rothschild, economist (Microsoft Research):

- Proposed to address misinformation as a market problem, framing it in terms of outcomes, such as exposure to information and its impact on opinion formation and decision making.

- Noted that research in the field tends to focus on what content people consume rather than the more difficult matter of how they actually absorb that information.

- Questioned whether mass ignorance on a particular issue may be more harmful than the consumption of fake news about that issue.

- Research may be distorted by over-reliance on Twitter data, which may not be as representative of news consumption by the general population as Facebook or television.

Kazutoshi Sasahara, computer scientist (Nagoya University):

- Used a simple model to demonstrate that online echo chambers are inevitable within the current social media mechanisms for content sharing, which tend to clusters individuals into segregated and polarized groups.

What countermeasures are most feasible and effective and who can best deliver them?

Nick Diakopoulos, computational journalist (University of Maryland):

- Identified the three relevant actors to be considered: tech platforms, individuals, and civil society.

- Discussed which combinations of the three groups could be most effective in combating fake news.

- Platforms are particularly powerful, but they raise the concern of influencing public discourse through their algorithms, although this could be mitigated through algorithmic transparency.

- Civil society and individuals alone cannot fact-check everything.

- Concluded that the best partnership is between civil society and platforms.

David Mikkelson, fact checker (Snopes.com):

- Argued that fake news is only as problematic as poor journalism: the very news outlets that are supposed to question and disprove misinformation often help spread it.

Tim Weninger, computer scientist (University of Notre Dame):

- Addressed the lack of research on Reddit, a far larger platform than Twitter.

- Reported on findings that initial votes on posts have a strong impact on their final visibility, allowing coordinated attacks to game the system through a snowballing effect.

- A large portion of Reddit users merely scan headlines; most up or down votes are cast without even viewing the content.

Cong Yu, computer scientist (Google Research):

- Described the use of semantic web annotations such as the Schema.org ClaimReview markup to connect claims with fact-checking.

- Argued that artificial intelligence can be a powerful tool to promote quality and trust in information.

- However, recognized that users play a role in the spread of misinformation, which may be the most challenging problem to address.

Melissa Zimdars, communication scientist (Merrimack College):

- Reported on efforts to collectively categorize news sources in an open-source fashion.

- Recounted how, ironically, her research became the target of a fake news campaign.

Identified major research questions related to each of the three panel questions

Research challenges #1: How to define and detect misinformation?

- Identifying and promoting reliable information instead of focusing on disinformation

- Tracking variants of debunked claims

- Developing reputation scores for publishers

- Creating an automated trustmark to promote journalistic integrity

- Collecting reliable crowdsourcing signals

Research challenges #2: How to best study the cognitive, social, and technological biases that make us vulnerable to misinformation?

- Investigating the use of language, images, and design in misinformation persuasiveness

- Validating model predictions via field experiments

- Studying the roles of algorithmic mechanisms in the spread of misinformation

- Translating research findings into policy recommendations

- Accessing behavioral data from social media platforms

Research challenges #3: What countermeasures are most feasible/effective and who can best deliver them?

- Support and scaffold critical thinking

- Increase prominence and availability of fact-checking information

- Design trust & reputation standards for news sources and social media users

- Build tools to track the provenance of digital content

- Develop computational tools to support fact-checking

Header image source: ICWSM 2017 Workshop on Digital Misinformation.

Also published on Medium.