Change hack 2: Hacking change with the magic numbers [Change hacks series]

This is part 2 of a series of articles on ‘change hacks’ from expert change management speaker and facilitator Lena Ross.

There’s lots of stuff we already know about our human hardwired behaviour. For example, we know that our brains haven’t really changed physiologically for over 200,000 years. And we know our survival instincts kick in when we feel we are under threat.

Then there’s the stuff we know at a deeper, subconscious level. The stuff that’s not top of mind that we don’t consciously practice day-to-day, but can make significant impact once we are aware of it.

And it seems, knowing a little about how numbers relate to our hard-wiring can translate to substantially positive outcomes in the workplace.

Group numbers

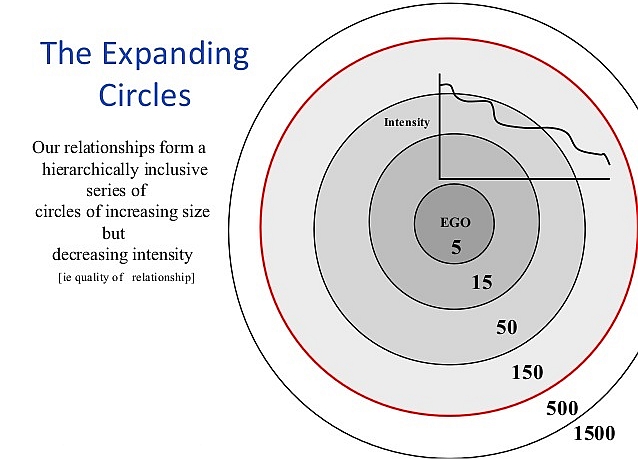

How cool would it be to have a number named after you? That’s exactly what happened to Oxford evolutionary anthropologist and psychologist, Robin Dunbar. In his extensive research on primates and his fascination with the amount of time and effort spent on social grooming, he came across an interesting social pattern1 that applies to primates and humans alike. He discovered that the size of our brains determines the optimal group size we have formed as social creatures.

So (drumroll)…for humans that ideal number for an extended social group size is 150! Interestingly, the world’s remaining hunting and gathering clans are made up of around 150 people. Once group membership exceeds 150, the relationships are less meaningful with a diminished sense of connection. If you are keen to start your list of your top 150, Dunbar’s rule of thumb is this—think about the number of people you would feel obligations towards and would happily do favours for.

Our personal clan

Dunbar continued his research to uncover a further three levels of social interaction. At the most intimate level, your closest support network numbers five. These are your closest family members and/or friends. The next level is your circle of fifteen best friends who will support you and you can confide in. At the next level are your good friends—the ones you would invite to a gather at your home. This number is fifty. Interestingly, when Dunbar carried out research on two poll groups of Facebook users in the United Kingdom, he discovered the first group had an average of 155 Facebook friends, the second group 183. More than the optimal number of 150-ish Facebook friends would suggest acquaintances or people who are likely to be friends of friends.

The workplace clan – family, village, tribe…

So if 150 is the maximum number of people we can maintain a trusting relationship with, what does this mean when we work in large organisations employing tens of thousands of people?

Some businesses are already realigning their organisational architecture so their business units are broken down into teams of 150 or less.

For example, Flight Centre has adopted a family-village-tribe operating model that is inspired by Dunbar’s thinking. Employees are assigned to small ‘units’ or teams called families. The next level is the village with a maximum of 50 people. The next level up is a ‘tribe’ that is made up of no more than 20 teams, so a tribe is no larger than 140 people. Families of three to seven people (the closest unit in Dunbar’s model) are accountable for their profit and loss and compete with other families in their tribe.

The change hack

Finding out more about our primal social patterns can point to clues that can make us better in our professional and personal lives.

When changes are being made to business unit realignment, or project teams are being established, we can look for opportunities to follow the Flight Centre model and align team and unit sizes to Dunbar’s ‘magic’ numbers. A large scale organisation can be made up of numerous units of 150-ish employees, with smaller teams of around 20 people to promote collaboration and optimal social connection. An approach that is intrinsic to our human make up translates to improved human performance. In turn, improved human performance is linked to better business performance.

If there are more ways to improve the productivity and adoption of your people during change, what’s stopping you? What can you do as a leader or change practitioner to tap into our primal preferences? For additional information please see my website.

Next edition: Change hack 3: Hacking employee engagement with five lessons from Candy Crush Saga.

Article source: Change hack 2: Hacking change with the magic numbers.

Header image source: numbers by Jurgen Appelo is licensed by CC BY 2.0.

Reference:

- Dunbar, R.I.M. (1998). The social brain hypothesis. Evolutionary Anthropology, 6, 178–190. ↩